A Note to the time-conscious reader: If you want to directly jump to the dialogue, move the video needle to 22:24 where the conversation begins with these wise agritech Yoda mentor friends of mine, after setting the context for divergent agritech futures. What follows below is the long-form text of my presentation at the town hall where I set the context for exploring divergent agritech futures, kickstarting Season 4 of this newsletter after a few throat clearings.

Upcoming Public Event in Agribusiness Matters: Organic Food Branding Master Class with Shashi Kumar, Founder and CEO, Akshayakalpa Organic and Ryan Siwinski, Director of US Operations, Good SAM, who brings his rich ops experience in building regenerative food brands in Rodale Institute and White Oak Pastures. You can RSVP here.

Dear Friends,

Soon after my last town hall, “Is Agritech Party Over”, in which Mark, Shubhang and I gave the old, calcified legs supporting ‘agritech’ a proper burial, I realized that I needed a break from writing Agribusiness Matters to clear the cobwebs off my agritech hat.

I took a break from work to explore the incredibly beautiful Indian coastal state of Odisha, meeting legal shrimp farmers and illegal prawn farmers along the way.

You can stay away from work, but your work won’t.

I titled this first ABM townhall session after my vacation “Divergent Agritech Futures” (that is Futures with an S) for the same concerns Nigerian Novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warned us of the dangers of a single story in her famous TED talk.

“The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.” - Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

If you have been squatting long enough in the agritech trenches like me, you would intuitively know the single story I am talking about, epitomized in classics like “A World Without Agriculture” by Peter C. Timmer and more recently, “Regenesis” by George Monbiot.

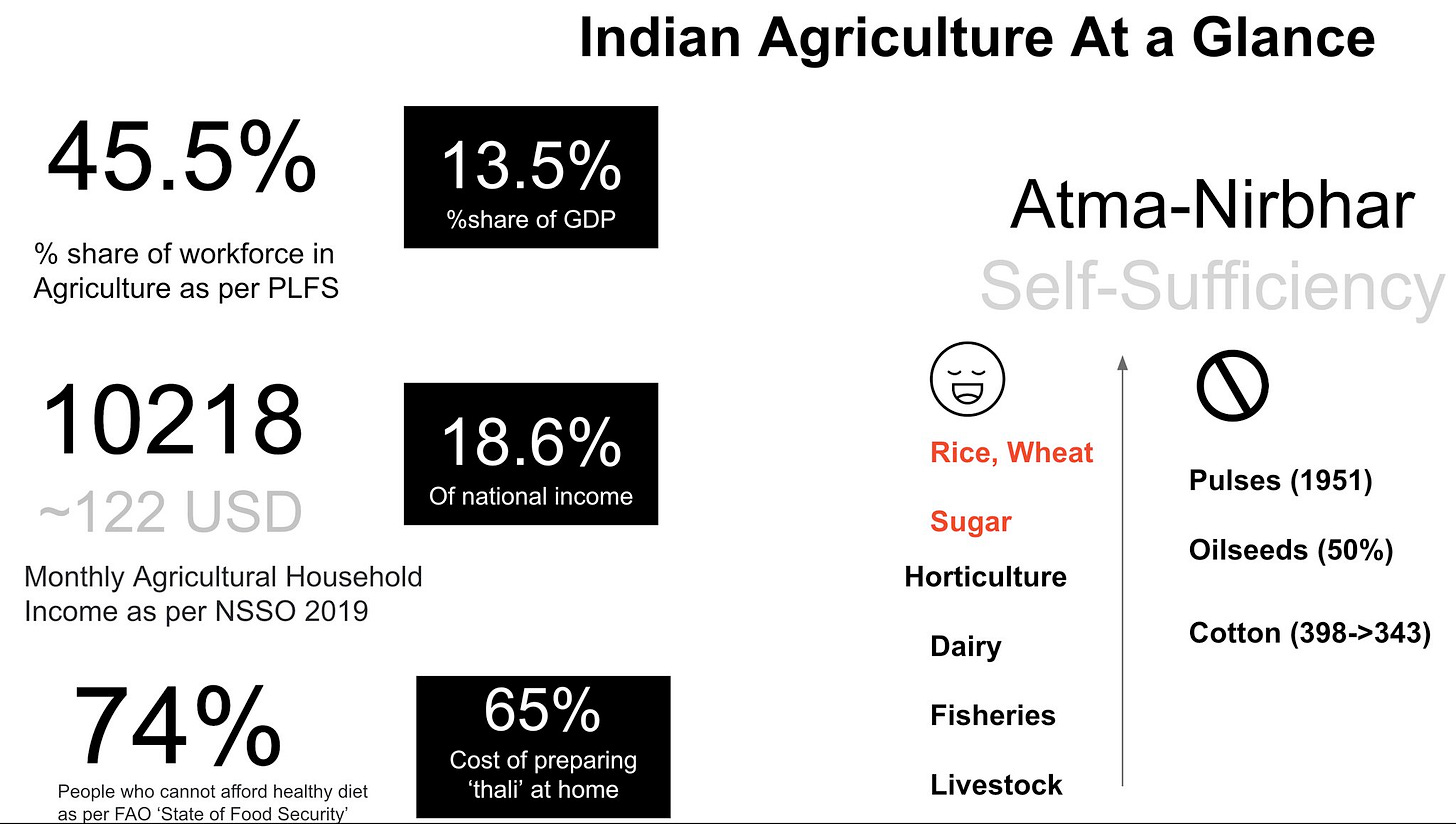

Agriculture is a funny domain where prevalent economic theories hold the fancy idea that the future of agriculture is bright only when many people (and cattle) leave agriculture. What does ground reality in the Indian smallholding context look like? As a prelude to the dialogue, I presented a quick (but incomplete) snapshot of Indian Agriculture to the members.

Where does Indian Agriculture stand today?

If you look at Indian ground realities, more people are returning to the safety of agriculture in desperation while moonlighting with construction and informal gig economy in off-seasons, thanks to the labour support provided by family members.

In 2018-19, 41.4% workforce of this country was dependent on agriculture. By 2020-21, the numbers rose to 45.5 %, thanks to the pandemic, whose effects are continuing to show up in different places (household savings, for instance).

This naturally creates a labour productivity imbalance in a country where there are more agricultural labourers (~100 Mn) than farmers (~50 Mn full-time ‘middle-class farmers’) who derive their income solely from farming operations.

One of the gravest consequences of this imbalance is that the vast majority of people cannot afford to have a healthy diet. Thanks to food inflation, as one study recently pointed out, in Mumbai city, over 2018-23, the cost of preparing a thaali (a meal plate) rose by 65%. Even if you are prone to dismiss these studies as politically motivated, there are diverse data sets (National Family Health Survey, FAO, low millet production in 2022-23) all pointing to the same fact that we are not providing a healthy diet to the poor, which further affects their ability to work in farms

How has India been faring in its ambitious goals of being self-sufficient aka atma-nirbhar, in an age of geopolitical volatility?

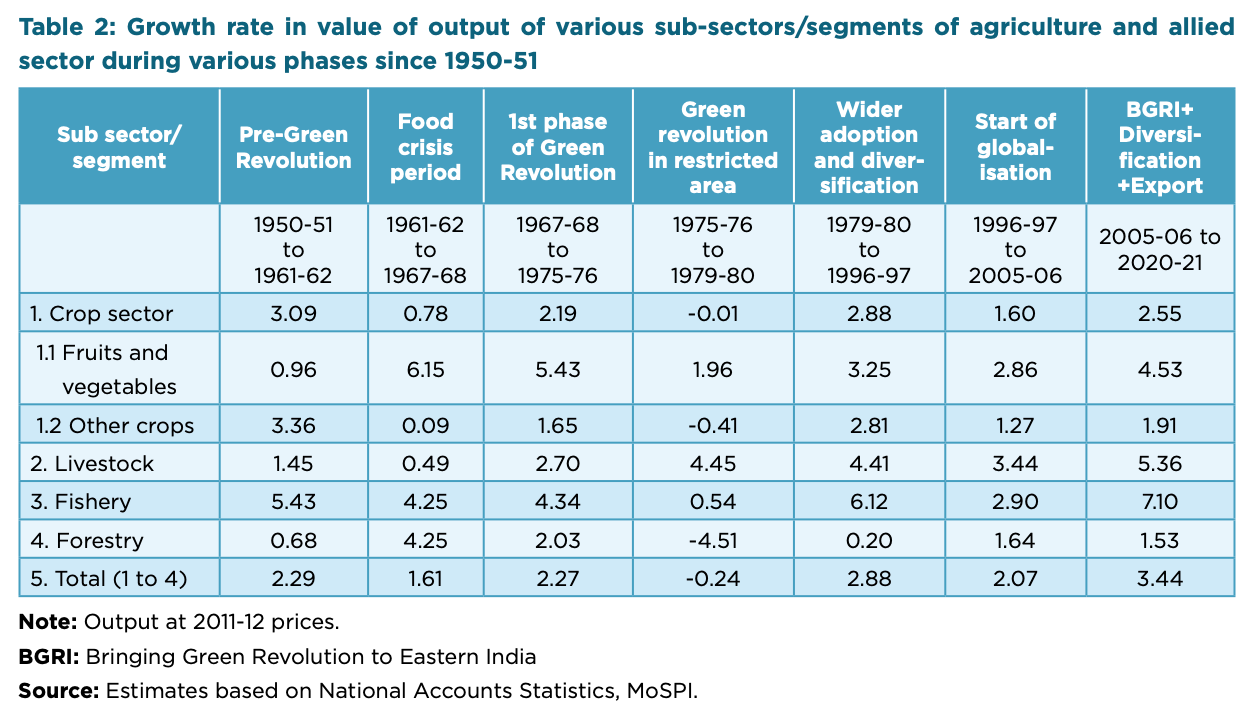

While we are producing way more rice, wheat, and sugar than required and becoming the diabetes capital of the world, thanks to perverse incentives provided by the governments which want to do output price support, we have been doing good in growth numbers, when it comes to milk, meat, fish, livestock and horticulture, if you measure growth at a composite level.

Fisheries have been the most impressive sector, registering 7.10% growth between 2005-06 to 2020-21 with no government support.

(Data Source: Niti Aayog Report on Agriculture during Times of Amritkaal)

In other words, the enterprising spirit of Indian farmers shines in sectors with the least government support (in the form of input and output prices).

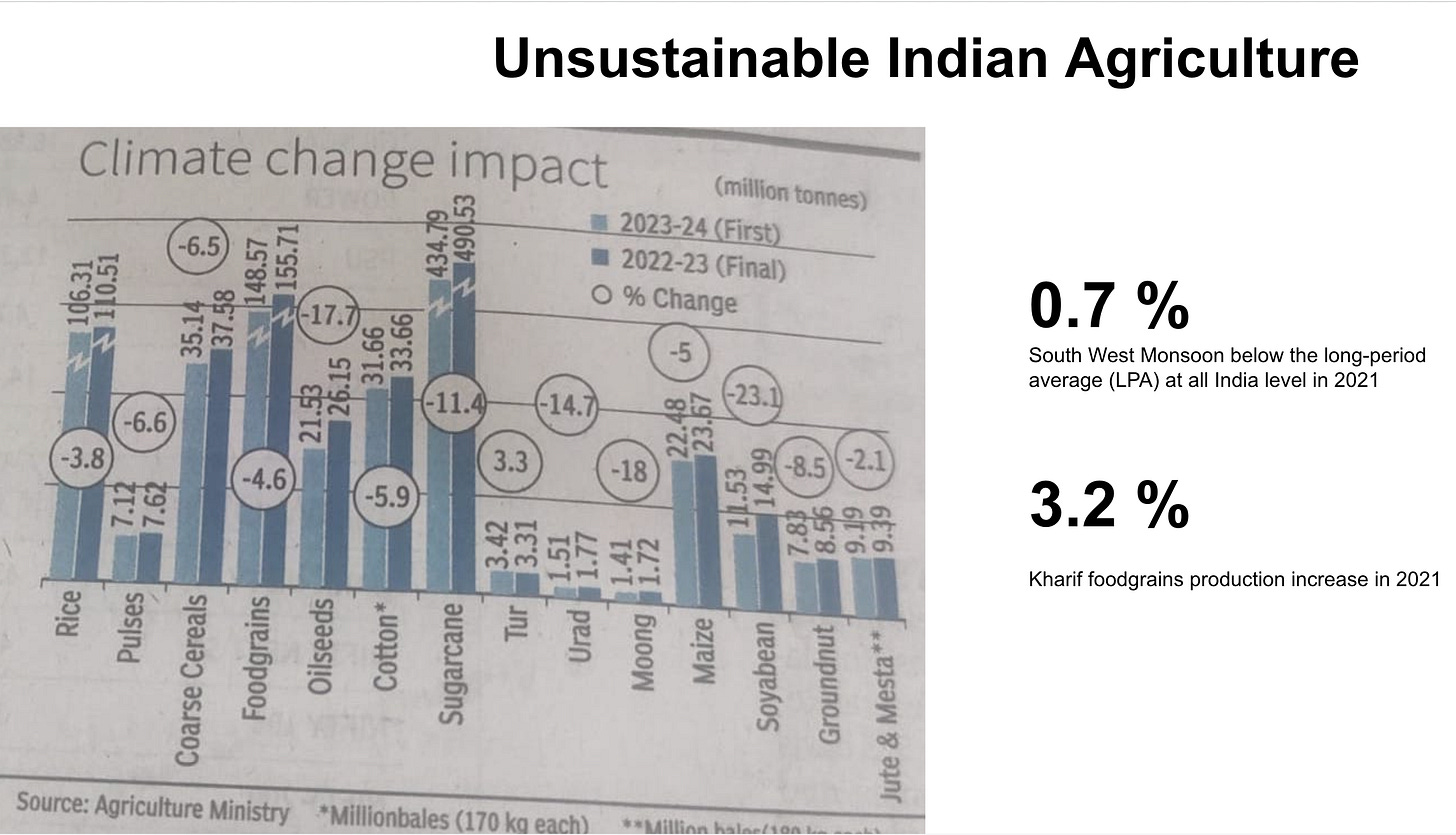

In which value chains we are yet to reach self-sufficiency? We are currently producing fewer pulses (at a per-capital level) than we did in 1951. Most of the Tur Dal we consume in Indian homes comes from Mozambique. Per capita production of pulses during the 2011–20 period came down to 15.7 kg from 23.3 kg during the decade of 1960s. We can meet only 50 % of our oilseeds demand from the domestic markets. Cotton production has fallen from 398 lakh bales in 2013-14 to 343.47 lakh bales in 2022-23

If sustainable poverty is an essential trait of the current state of agrarian affairs, how are we doing on the sustainability front?

When you look at the Indian Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare’s first advance estimates (2023-24), where the output of almost all kharif crops, barring tur (pigeon pea) is lower, the reading on the wall is clear - Climate change is a fixture in our agrarian affairs, although things are brighter when you examine the dependency Indian agriculture has on rainfall monsoon.

In 2021, when South West Monsoon ‘was 0.7 per cent below the long-period average (LPA) at all India level, kharif foodgrains production increased by 3.2 per cent during the year’.

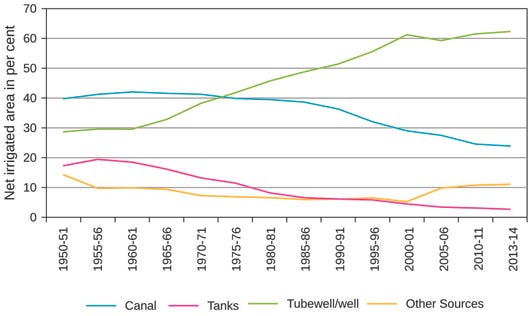

There is reasonable empirical data to point out that ‘irrigation mitigates the adverse consequences of monsoon deficiency on agricultural production’, although, despite our best efforts, groundwater irrigation remains the last, desperate private irrigation source to tap into.

“Surface water irrigation (canal and tank) accounted for 57 per cent of total net area irrigated in 1950–51, but declined to 27 per cent in 2013–14. In the same period, the share of groundwater irrigation in the total net area irrigated increased rapidly, from 28.7 per cent in 1950 to 62.3 per cent in 2013”

We continue to foster deep inequality between irrigated farmers and rain-fed farmers with the latter ending up shortchanged often.

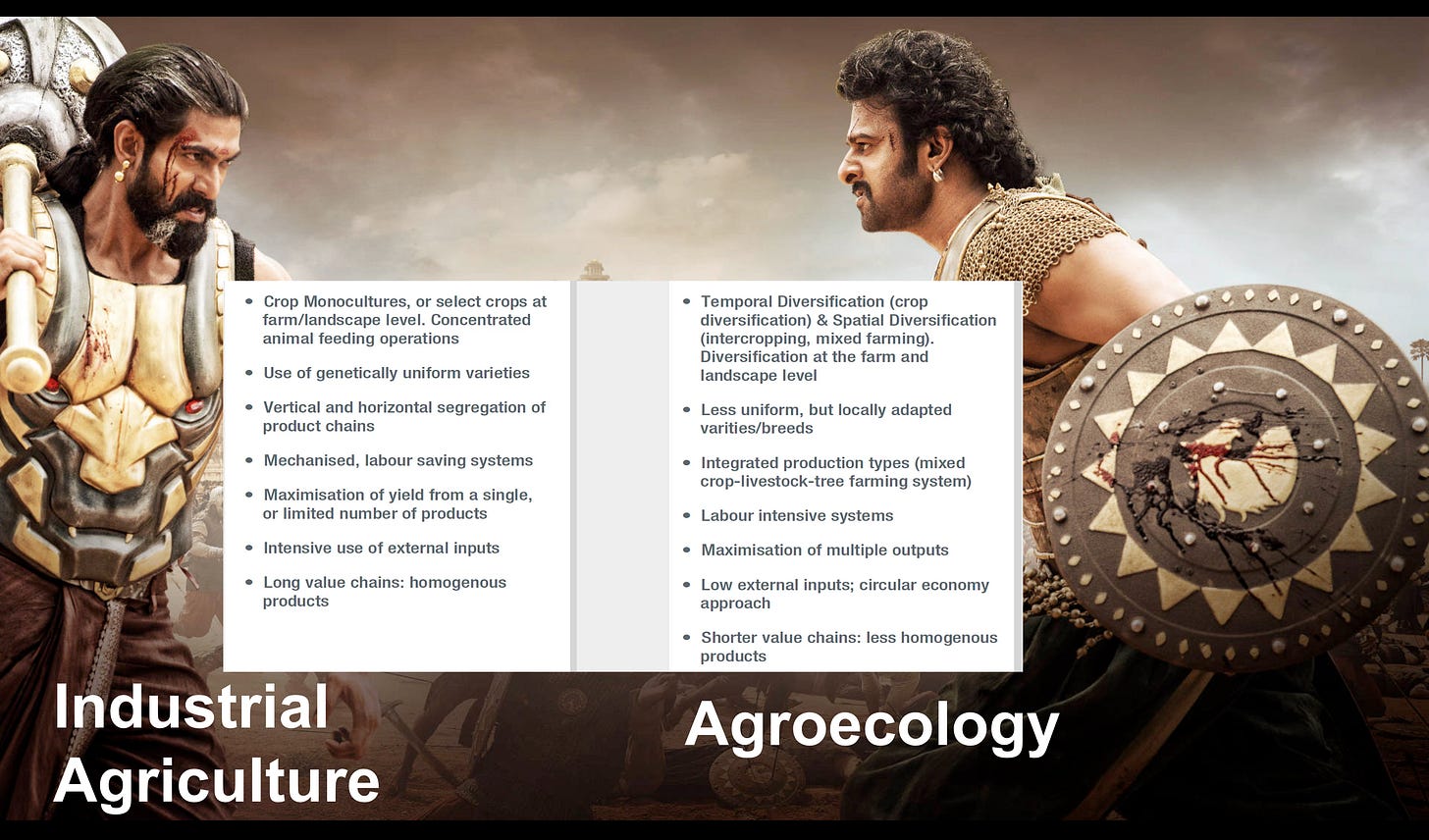

And so the average farmer is trying to fight through the feudal choke points while navigating a clash of paradigms between Industrial Agriculture and Agroecology.

When we take full stock of where we are AND explore the possibilities, you will explore divergent agritech futures.

Could it lie in labour-arbitrage-driven corporate farming endeavours where farmers are given a fixed monthly salary for them to hone their skills as agritech operators and enter the global labour market for agritech operators?

Could it lie in nuanced agrifintech gameplays that squarely address intergenerational caste-driven poverty?

Could it lie in unbundling age-old behemoths like the Food Corporation of India and providing village-level entrepreneurs with decentralized infrastructure (grain silos) that could create agglomeration effects and help them be a part of the digital transformation of Indian Agriculture?

Could it lie in decision support systems like Krishi DSS ( Yet to be launched) that could enhance ‘the evidence-based decision-making capability of all the stakeholders in the agriculture sector by way of integration with MOSDAC and BHUVAN (Geo-platform) of ISRO and systems of ICAR?’

Could it lie in decolonising agriculture where we go back to the past to discover conservative futures?

Could it lie in group buying, financing and selling of commodities through marketplace modalities?

Could it lie in the farmer creating their brands and owning every component of the value chain?

To explore these divergent agritech futures, I sat down with Jagadeesh Sunkad and Emmanuel Murray, my dearest agritech Yoda mentor friends with whom I’ve had the privilege of dialoguing for a very long time ever since I started to think deeply about agritech.

Some of you might remember my agritech dialogues with Jagadeesh Sunkad where we explored the bull-whip effect in the agri-input supply chain and agri-output supply chain, unravelled the secrets of the soil and more importantly the central promise of Indian agritech to address the agrarian crisis we see in our midst.

Some of you might remember my conversations with Emmanuel Murray where we explored the promise of Farmer Producer Organisations, the state of agrifintech 2022,

It is almost impossible for me to summarize this dialogue.

In this conversation, along with longstanding ABM member Vivek, we explored many fundamental questions (Should farms be prioritized over farmers ? Is there a binary between the two?)and navigated the maze to discover deep underwater springs of optimism when everything feels bleak at the moment.

This conversation was deeply nourishing at an ineffable level and filled me with a lot of optimism to fall in love with technology again and play the long marathon game. I hope you enjoy the conversation as much as I did.

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Agribusiness Matters”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.