In rare moments of ethereal wonderment, I ponder over the famous Buckminster Fuller’s quote: “There is nothing in a caterpillar that tells you it's going to be a butterfly." For it points out a truth that often vanishes like a puff of smoke: Fundamental shifts are the hardest to pay attention to.

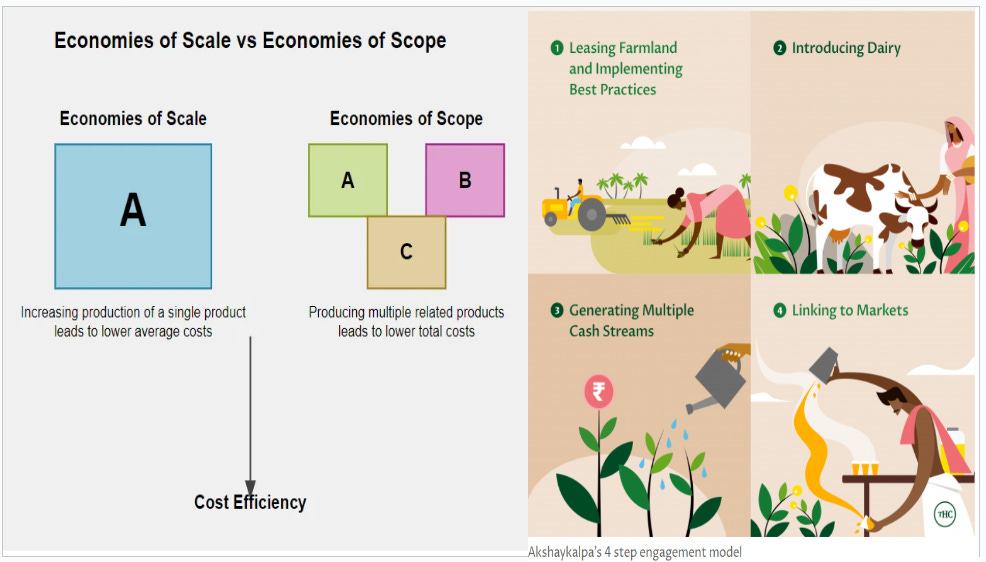

Diligent readers of Agribusiness Matters must have heard me croon this choral line often: The future of agriculture would precipitate a shift from Economies of Scale to Economies of Scope. In my Global Agritech 101 course, I spend a lot of time on this.

Economies of scale and scope are both types of learning. Economies of scale are the advantages that can result when repeatable processes are used to deliver large volumes of identical products or service instances. Scaling relies on interchangeable parts either in the product itself, or in the delivery mechanisms, in the case of intangible services.

Economies of scope are the advantages that can result when similar processes are used to deliver a set of distinct products or services. - Venkatesh Rao

Recently, someone asked me: Why do you think economies of scale is giving way to economies of scope? Isn’t it counterintuitive to how industries evolve?

Fair point. Let us take the case of biologicals.

Why do ‘most biological innovations come from small companies’? Why do ‘organisations built to sell chemicals and seed struggle to learn how to integrate biologicals’? Why have ‘none of the big crop protection companies yet developed strong biologicals R&D capabilities’? (Source: Highlights from Dunham Trimmer Presentation at 2024 Salinas Biologicals Summit, Hat Tip:

)Big crop protection companies have been largely incentivized for ‘industrialization of biotech’ (aka economies of scale) while strong biologicals R&D requires ‘biologization of industry’ (aka economies of scope).

It may seem like a clever play of words. Mind you, if you dig six inches deeper into the science of biologicals, it makes a whale of a difference.

As

puts it in his wonderful, “Atoms are Local” piece,“As Endy likes to say, “biology teaches us that atoms are local.” This is a really important idea. Fundamentally, biological systems are built using only the local resources in their environment, and the information in their genomes. Put more simply:

The leaves on a tree don’t come from a factory and then get shipped to where the tree is going to be and taped and stapled to the twigs and branches. The photons and molecules arrive where the biology is going to grow and the biology grows locally.

No wonder when you are dealing with biologicals, you are dealing with a multivariate riddle of consistencies.

For you are grappling with consistencies at the product level (vulnerable to degradation and shorter shelf life), performance level (affected by the microbiome of the crop with low knock-down effect), and last, but not least, improper application level requiring deeper understanding of agronomy and crop life cycles.

“We have heard directly from farmers that they are ready and willing to try novel biological amendments, but that the efficacy has to be at least close to the products they are already using,” - Elliot Kellner in AgFunderNews’ sponsored article by Pam Marrone on the occasion of Salinas Biologicals Summit 2024

Can you see here how our notions of consistency and efficacy are wedded to earlier notions of industrialization of biotech, as opposed to biologisation of industry?

Nobody is saying that efficacy and consistency have to be sacrificed. For biologicals to scale and be rapidly adopted, our notions of efficacy and consistency have to be rethought.

Brazil’s success in scaling decentralized bio-fertilizer farmgate infrastructure shows that this is possible in the right regulatory environment. We (as in biological folks from the US, Europe, and India) haven’t cracked the code yet, especially in regulatory dimensions.

As I write this, India is attempting to tame the Godzilla Monster of Fertilizer subsidy by setting up decentralized bio-resource centres where farmers are provided with mother cultures for Trichoderma Viride and other biologicals to sell at the downstream end.

The case for economies of scope over scale isn’t limited to biologicals.

Let us take the case of farmer enterprises.

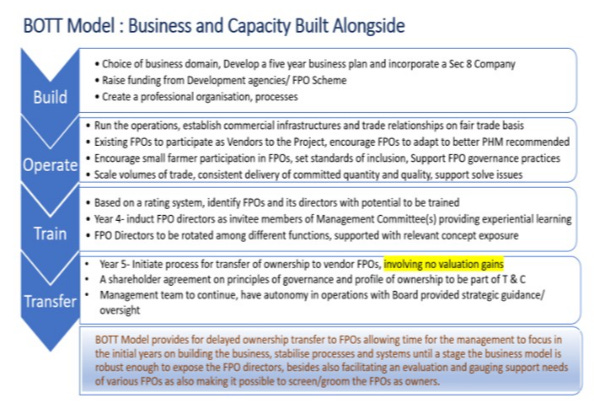

Why are farmer enterprises designed to scale by federating multiple FPOs into an apex to build an institutional leadership structure professionally managed to grow into large businesses?

Fundamentally, agricultural activities that require intensive labour inputs on an everyday basis, such as cattle breeding (for milk or meat) require multipurpose collaboration and hence economies of scope are much more suited than economies of scale to build the DNA of farmer enterprises.

Is that why India based Akshayakalpa dairy model is centered on making smallholder farmer farms financially viable, by generating multiple cash streams, thereby building circular economic models at the intersection of assured livelihoods and sustainable farming systems?

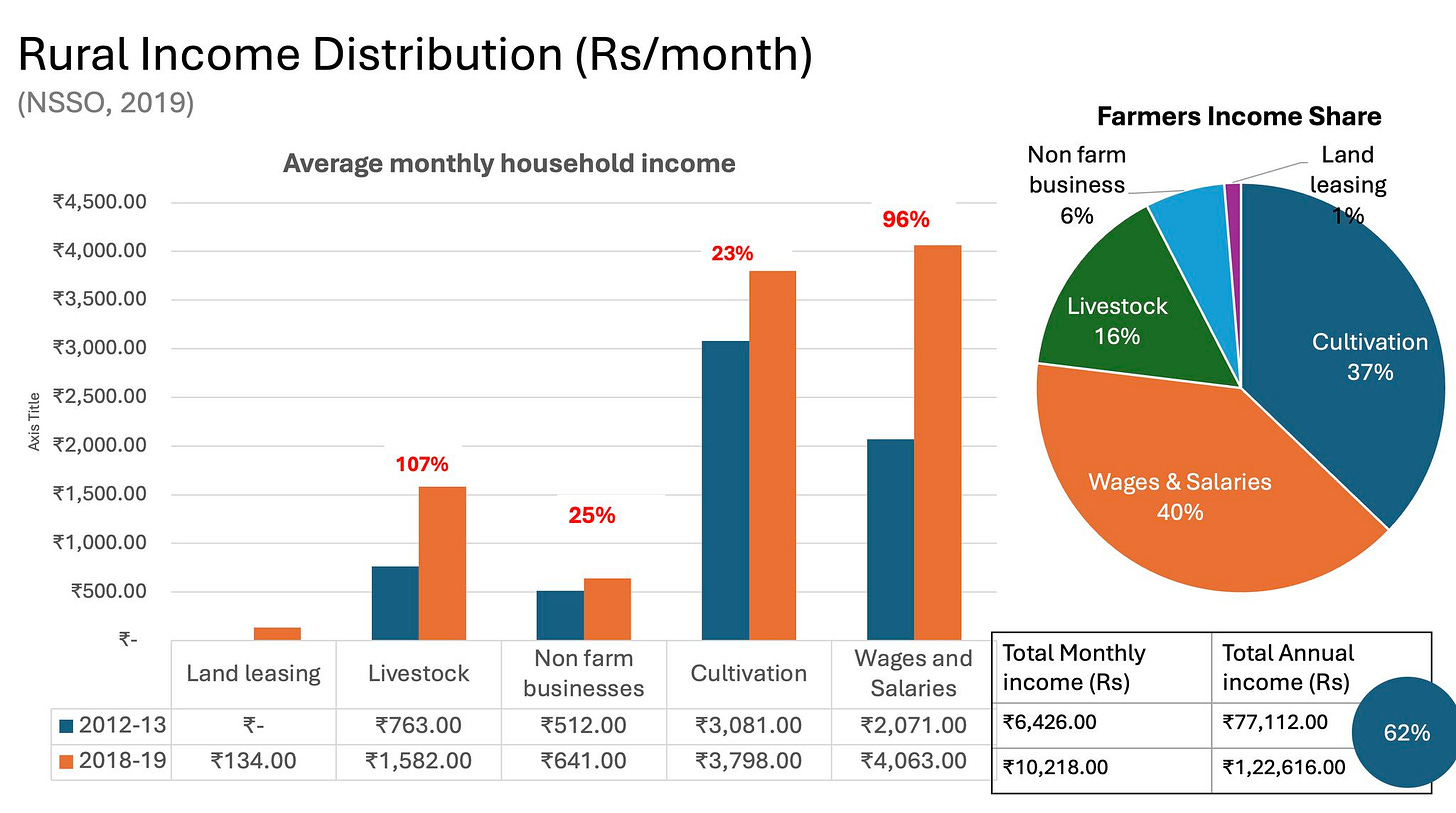

In an Indian context, when income share from crop cultivation is just around 1/3rd of the total house hold income, a strong empirical case for economies of scope (with much stronger focus on non-farm incomes) becomes plainly obvious.

There is a reason why economies of scope hasn’t received enough attention as opposed to economies of scale in the history of economic thought.

It goes back all the way up to Adam Smith.

“In his book Wealth of Nations, Smith (1776) discusses the notion of economies of scope in the light of how division of labor is limited by the extent of the market for a product or service. He observed that a person needs to engage in multiple activities because the product or service that a person offers is limited to the nearby smaller market and cannot be sold in far off and large markets. In other words, scope limited growth and for one to reach his product or service in far off larger markets, he has to specialize on a particular product or service. In the context of industrial culture and production economics, Adam Smith and the other leading economists were indeed right and rightly so, they unintentionally buried the idea of economies of scope.”

Here is the thing.

Our bases of efficiency vary significantly between agriculture and industry.

When we are dealing with open systems of agricultural production, with individual adaptations that have been tested by millions of years of evolution in improving biochemical processes like photosynthesis, we are now rediscovering that economies of scope is the natural logic that dictates the basis of efficiency and sustainability in agriculture.

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Agribusiness Matters”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.