Great Expectations: Setting the Context for Farmer Producer Organisations (FPO)

FPO stocks are trading high in the marketplace of hope. How do we make sense of this promise without losing touch with ground realities? I speak to FPO Expert Dr. Venkatesh Tagat to find out.

A lot of attention is being lavished currently in India on the promise of Farmer Producer Organisations - the intrepid love child of private companies and cooperative societies. So much that Spiritual Gurus like Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev (SJV) are now talking about it. And if you know anything about how urban India works (mind you, we are not talking about rural Bharat), that’s a big deal of attention.

In one talk addressed to agricultural students, SJV had this to say to beaming young minds and bright eyes filled with promise.

“Young people can go out and form “Farmer Producer Organisations” and aggregate 1000, 2000, 10,000 farmers, depending on your capacity. And if you aggregate irrigation and marketing, and the farmer just does farming, you will make a miracle happen in this country.”

Going by the amount of public money that is being diverted for FPOs, one thing is for sure. A lot are betting on this collectivisation-of-farming miracle to happen.

The central government recently launched a new scheme "Formation and Promotion of Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs)" to set up 10,000 new FPOs with a budgetary support of ₹ 6,865 crore INR from FY20 to FY28. And more recently, as per the new operating guidelines, the government announced that they will provide financial support of upto ₹18 lakh INR to new organisations for the first three years.

While critics have argued that such grandiose plans are bound to fail without adequate funding reforms that take into account the time it takes for FPOs to grow and mature, I don’t see several fundamental questions being asked in our rush to bet on FPOs.

How do we make sense of FPOs as it is imagined in the rose-tinted world of optimism AND as it is in the real world where the rubber meets the road?

This is a vast topic, and I plan to cover FPO in greater depth.

To set the ball rolling, I want to begin with an interview I did with Venkatesh Tagat few moons ago. Special thanks to Emmanuel Murray for introducing me to Venkatesh Tagat.

Venkatesh’s deep immersion and vast experience in this space is extremely useful to set the context for our future exploration on this hairy topic.

And mind you, this is a topic that is not just relevant in an Indian context.

Even in countries like China, the rise of youtube stars like Li Ziqi clearly point towards the vision of People’s Republic of China to encourage millennials to leave overcrowded cities and go back to their native villages and start farmer cooperatives, leveraging the power of the technology they know at the back of their hand.

Now please allow me to introduce our guest.

Venkatesh Tagat is an independent consultant and wears many hats. He currently sits on the Board of Samunnati as an Independent Director.

I analysed Samunnati’s central promise for smallholder farmers many moons ago incase you wish to delve deeper. He has had a fascinating journey in Agriculture.

Starting from a research career with Coffee Board in Karnataka, he got recruited by the Reserve Bank of India, joined NABARD [National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development] in its early halcyon days 35 years ago, and before his retirement, was actively involved in enabling credit for Farmer Collectives: Co-operative Society, Farmer Producer Organisation, Farmer Producer Company, Mutually Aided Co-operative Society [in states like Andhra Pradesh that have passed a liberal co-operative law on the principles of mutuality).

Now whichever institutional model route we take [and we will explore the trade-offs for each route at some point in the future], the core objectives for farmers to setup Farmer Collectives are simple and straightforward.

Can farmers get access to inputs at cheaper cost?

Can farmers get support for marketing?

Can farmers get a “little better price”[In Venkatesh’s words] for their produce?

What drew me into this conversation were precisely these words of cautious optimism from Venkatesh. And I began this conversation from there.

Edited excerpts from the interview.

Venky: What makes you say “a little better” prices for farmers. Where does this grounded optimism come from?

Venkatesh: This is very difficult for FPOs and institutions which are managing FPOs. Markets are still not developed for many products. I often give this example. Out of total 250-275 million tonnes [MT] of food grains in our country, more than 200 MT comes from two crops: Rice and Wheat.

For both of these crops, the major player is the government and they are MSP[Minimum Support Prices]led. That leaves very little scope for FPOs to play around. They can only play around with other minor crops like pulses, oilseeds, and of course, millets. Since most of these crops have better MSP than wheat and rice, farmers are looking at these.

One of the other reasons why I say this is because governments can impact the whole process. To give you an example, if the prices of onions rise in the market, government says, "Let's import and bring the prices down". The concern of the government is more for the consumer than the producer. It's only when the prices fall down, governments open the gates for exports.

As far as vegetable and fruits are concerned, the vegetable market is dominated by Potato, tomato and onion[POT], though they're typically not vegetables - Onion is a spice and potato is more a starch crop. These three form the bulk of the vegetables consumed in the hotel sector. The prices of these three commodities fluctuate so badly. Stubborn farmers grow this year after year, despite knowing that prices can take a hit.

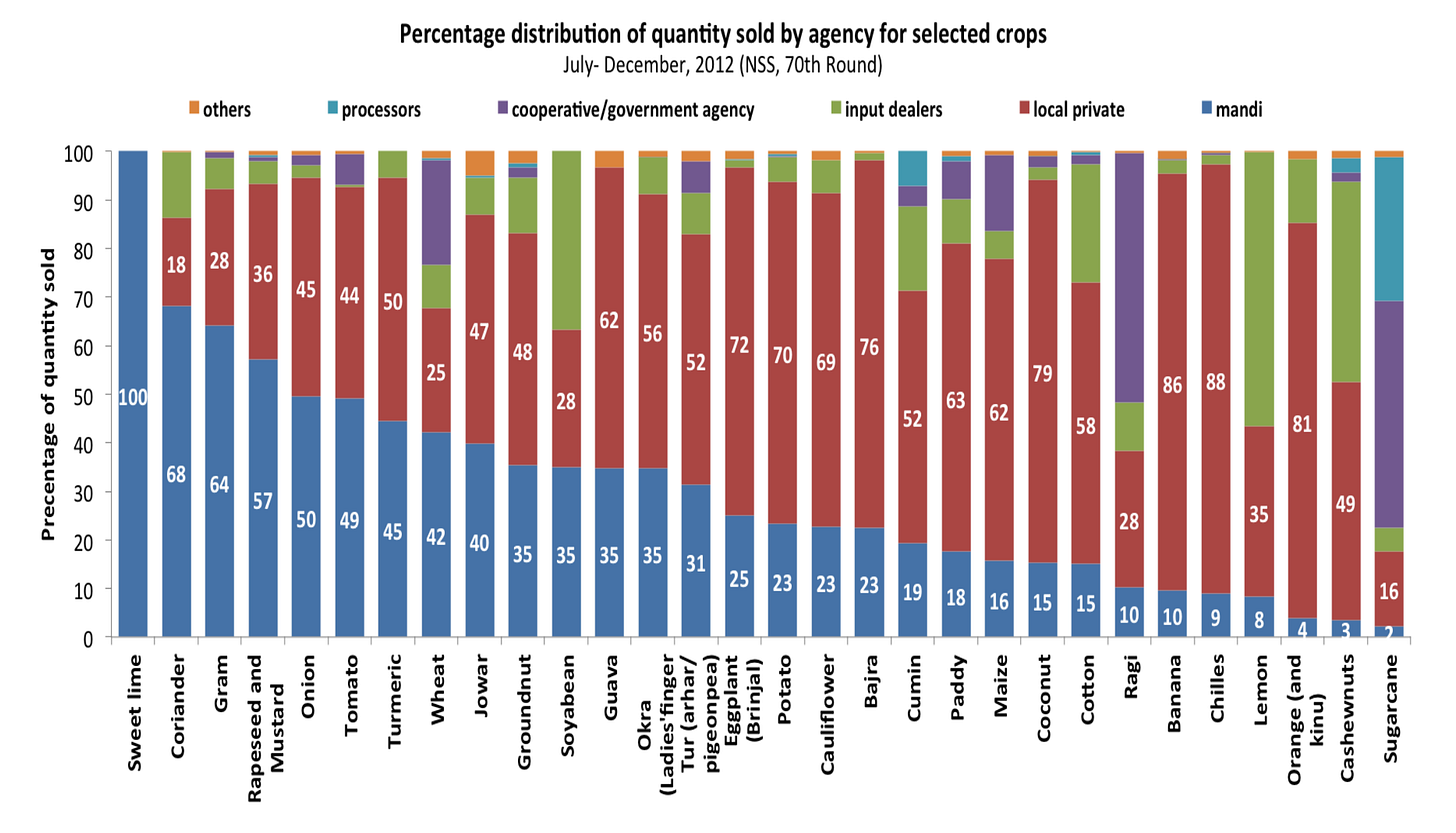

These farmers maintain that 'Once in two or three years, we will hit a bumper price. It will make a lot of money. It doesn't matter to us whether in one year we lose money and throw away tomatoes.' You will find potato farmers of West Bengal of similar nature. So is the case with the Onion farmers of Nasik. Venkatesh’s first point about markets not being adequately developed will become much clearer when you consider the percentage distribution of quantity solid by various players, based on NSS 2012 data. [Such an old data though.].

See for yourself the quantity sold by cooperative/government agency vis-a-vis mandi, and you will understand the scale of where FPO’s are in context with the traditional agency players.

Venky: If you consider today an average small landholding farmer, typically, when he or she is presented with a proposition to join an FPO, maybe by his friend or neighbour, how do you think he or she would weigh in the benefit?

Venkatesh: Basically, what we have found in our studies is that farmer thinks that he will get something. Inputs that are less than market cost. This can be arranged in such a way that he doesn't need to spend money to travel. Typically, he has to go to nearby urban or semi-urban area to buy it.

There is a perceived belief, especially in many places in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, that government will give some benefit to them in lieu of joining FPOs. They aren't sure what it is. I met many FPOs that are being promoted by the Horticulture Department. They would say that they would get access to credit, (even if they didn't say 'subsidies'). They were very clear that they would get bank loan at a cheaper rate. This whole thing balloons when it goes into the village. Everybody say that by becoming members, they get these benefits.For example, SFAC says that if your FPO is registered under the Companies Act, if your members have put in share capital up to 10 lakhs, then SFAC will do an equal contribution of 10 lakhs to equity on behalf of your FPO members.They can't invest on their own. And so it goes into farmers' equity.

This also acts as an incentive to join.

Venky: So, when they share this, do you clarify the organisation’s objectives? What I am trying to get a sense is that, would there be a valid reason for someone to be deterred from joining an FPO?

Venkatesh: No, I think it’s more of a thing where everybody says, "Please Join. Please Join." A lot of them get convinced and join. These are more like farmer interest groups and those members start getting driven to become members of FPO. Many promoting agencies use this methodology where they create groups of, say, 20 farmers in two villages, and then start pushing them to become members of FPO. Venky: Earlier, I was looking at few data points on the interest rates charged by FPCs from NBFCs. Considering the fact that while credit is obviously pooled in, how does the cost of credit typically fare on the ground?

Venkatesh: Many of these people feel that access to credit is more important than the interest rate per se.If they go through the traditional agriculture input dealer route, the interest rates are very unclear, because that guy gives everything on credit and then buys the final product, which is not transparent. Compared to that, the farmer here says, "I am paying something less than that". These interest rates can normally be at 2% per month, vis-a-vis NBFC rates, can be seen lesser in terms of interest burden.

And also I think the way NBFCs look at this is that they usually give it for short term. Farmers repay very quickly. They don't need to wait for the crop to be harvested. They can pay back before that.

And also, it is the way it is presented to them. For example, some of them will try to help FPOs to get inputs - bulk rates from, say, manufacturers of fertilisers. Some of these NBFCs directly pay the fertiliser manufacturer, which is directly delivered to FPO. And then the FPO account is debited as loan from NBFC. To that extent, handling of money or mismanagement is reduced to a large extent.

Venky: Yes, and that’s where the technology could have a good role to play. Now that we are talking about technology, today, most farm-to-fork players have been working closely with FPOs for their supply. Digitising farm lands are also happening more smoothly in an FPO context. Now if I were to reverse the tables, how do you think FPOs view the digitisation of agriculture? Do they see it as a favourable trend or are there doubts that are yet to be ironed out?

Venkatesh: FPOs are deeply attuned to mobile apps and anything to do with mobile. Which ever is easy to understand, and mobile based, they accept it, use it more easily, and understand it little better. When we help in digitisation, we are also helping in crop planning, in an indirect way.

For example, I know of one group which was buying tomatoes for the hotel industry. They wanted me to introduce them to some producers. We had gone to FPOs in nearby areas.

The first thing the FPO member said was, "Tell us how much do you buy every week?"When they said they needed , say, a tonne every week, many of the members sat down and decided to plant tomatoes in such a way that they will have adequate production every week, rather than all of them putting it at the same time.

They can tweak planting days little bit. They also decided to buy vegetable seedlings from smaller players who have poly houses at different points of time to optimise production. Digitisation can further drive this.

In Karnataka, some of these FPCs also employ researchers to track historical prices of tomatoes to manage violent fluctuations of prices. They try to find out where the prices dips. Such kind of exercises can help marketing companies plan better. Digitisation can play a role here as well. Venky: At this point, how these digitisation scales in reach and impact is still not clear. What challenges do you think we could face in scaling these digitisation initiatives? As it is evident now, there is a flywheel kicking in with digitisation driving more FPOs and vice-versa. Do you foresee any significant challenges when we are dealing with things in a larger scale?

Venkatesh: One of the challenge which is facing FPOs sector now is loyalty. Their own loyalty to their company or collective is questionable. It is not well established. If tomorrow, a trader offers better price for their products, then they will go to him rather than to FPO - whether it's input or output. How do you build loyalty of members to an FPO?

It's like, in the cooperative movement, as we used to say, if your member of the cooperative lets you do business with a cooperative, the cooperative wouldn't benefit. At the same time, if the cooperative is not financially strong, they cannot provide services to their members. It's a double edged sword.

So on one hand, if 1000 members don't transact business with a company in which they are shareholders or members, it will affect the business of the Farmer Producer Company[FPC]. And at the same time, if FPC is not, because it is affecting their business, it cannot be financially strong and be able to help them access credit and markets. Then the members will slowly go away.

This is the point where we have to find out: How to help FPOs to gain member loyalty by giving them better services and at the same time, be financially strong? They cannot give this at low cost or at no profit. And then access to credit and markets can help them to create stronger loyal member base and financial base.

Based on this assumption, what we are seeing now in the marketplace is that technology can be a powerful driver - Can we build some systems and procedures where this can happen on a larger scale? Can we have adequate access to marketplaces and advanced farming technologies?

The key input here is to provide services to FPOs to manage compliance and regulation, because that is taking away most of their human resources and sometimes, even their financial resources.

Can these services be provided like a business unit support - Accounting, Auditing, Filing of Returns with Ministry of Corporate Affairs, GST Returns - to FPOs? Unless you have digital systems, these cannot be done so easily.

Today, banks are reluctant to provide credit. Can technology bring transparency to maintain accounts and access credit in an easier way?In the second part of this interview, we will explore deeper on the chicken-egg problem of member loyalty, the limitation of banks in providing credit, and how do we deal with the challenge of financing FPOs.

Stay tuned.