How do you solve a problem like agritech?

Reflections on my favourite spiel: "You can solve agritech only in ecosystem terms"

Couple of weeks ago, I took part in my first physical conference event after 2019. The event was special for various reasons. It had some of the leading movers and shakers of the Indian agritech ecosystem. It also had a few of my old friends and mentors who shaped my thinking on agritech and agriculture. More importantly, it was a powerful reminder of how complex things can get when you are trying to solve a problem like agritech.

If you go through the profile of the organizers, this will become obvious.

“ThinkAg, a not-for-profit organisation, is India’s leading AgFoodFin Tech Collaboratory platform bringing together innovators, corporates, incubators/accelerators, investors, FPO(Farmer Producer Organisations), Govts, and other stakeholders of the ecosystem to improve the outcomes in Indian Food and Agriculture. The Vision is to enable rapid scale up of AgFoodFin innovations by building a multi-stakeholder network, nurturing partnerships and creating knowledge, that will accelerate investments and adoption of technology in the sector.”

While this might sound extremely challenging (and coincidentally, over the past few weeks, I have been having private workshops/meetings with various ecosystemers of not-for-profit and for-profit kinds), this is no wishful thinking.

I can talk about myself.

I went on to quit my full-time role as a product manager in an agritech startup in 2019 and eventually founded Agribusiness Matters on the basis of this conviction.

But is there a logical argument behind this conviction?

You might as well argue that this is true even in the case of biotech which deals with an equally wicked problem of human health. What about agritech that makes it amenable to be solved in ecosystem terms?

A fairly compelling argument (in an Indian context) I have read so far comes from TCA Ranganathan which I reviewed in an earlier edition of Saturday Sprouting Reads.

“Rarely is it asked whether Indian agriculture could be suffering not because of farmers’ inefficiencies but more because of what is happening or not happening outside the framework of agriculture…”

“…A larger number of well-developed urban centres means that many more farms become closer to demand centres. Logistical efficiency improves. They thus get better prices. Also, most agricultural specialists (just like other professionals) prefer to live in cities due to living quality benefits. The extension support in nearby areas is thus better. Farm productivity is thus higher…” - TCA Ranganathan

Of course, you can also point out a few data points that farmer distress is higher around cities and countries that have witnessed high levels of urbanisation.

The underlying trouble boils down to this: When a particular income model for farmers starts to work well, overcrowding occurs among farmers and the produce prices start to take nose dive.

Since this is a newsletter that focuses on applying a system thinking lens to agriculture, I want to offer a tool that could help you think through YOUR agritech problem in ecosystem terms.

Given that there are enough signs that 2023 is likely to be an era of food insecurity, I want to offer a tool that will help you make sense of reality as you perceive it.

If I were to teach a semester course on system thinking in agriculture, the first module will be focused on understanding agrarian realities, based on Stewart Brand’s concept of Pace Layers

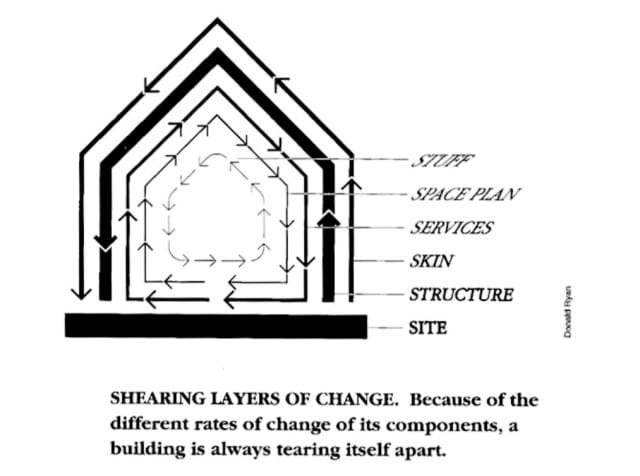

The concept originated when Stewart Brand, in his book, ‘How Buildings Learn’, describes a building having various layers that age at different speeds.

Can this insight help us design alternative food and agriculture systems?

In a continuously evolving domain like agriculture whose history dates back to the entire human civilization, some components respond faster to change and some not so fast. The key here is to understand which is fast and which is slow.

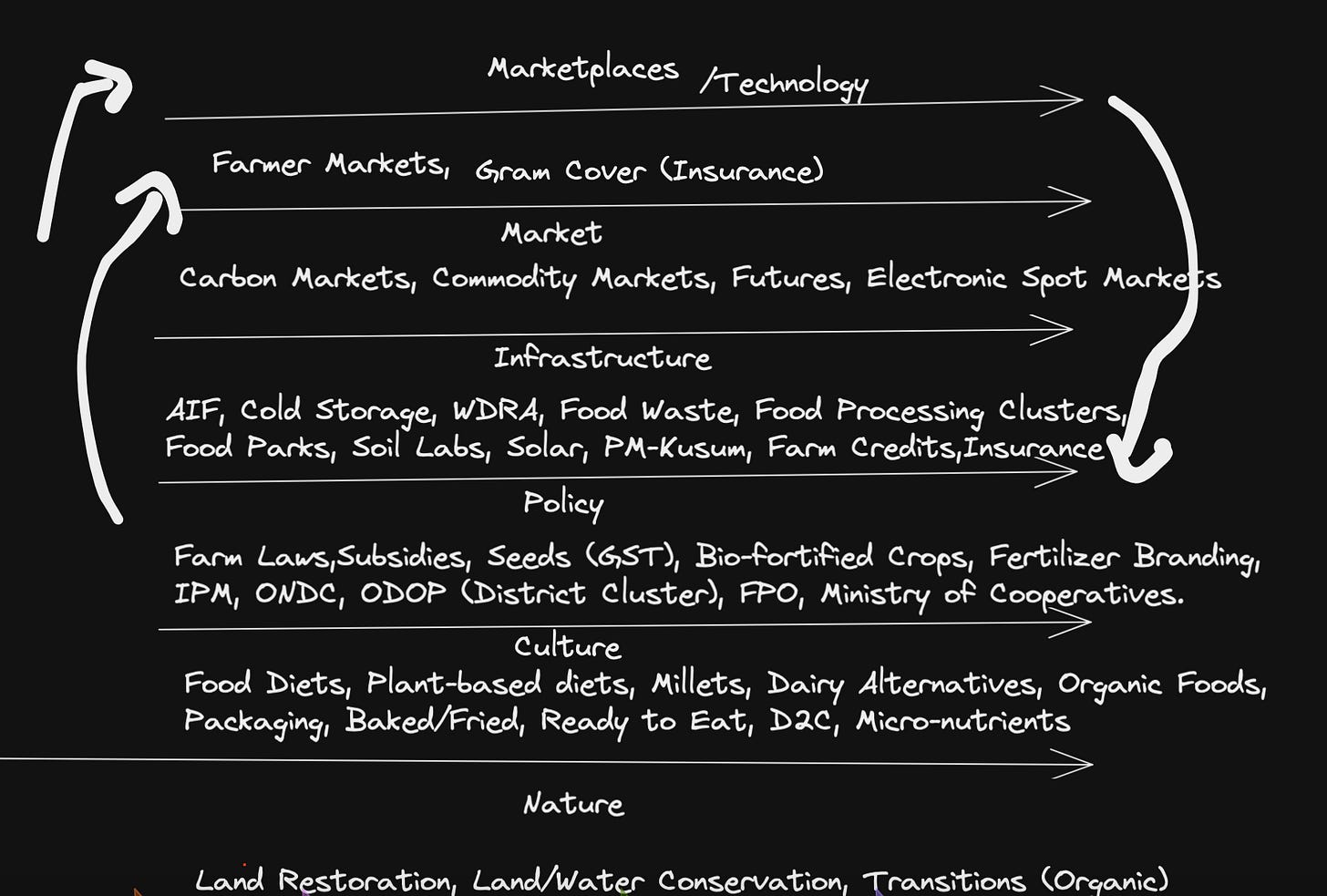

As a snowclone to Stewart’s model, I propose six significant levels of pace and size in the working structure of a robust and adaptable system of agriculture. From fast to slow the levels are:

Marketplaces

Markets

Infrastructure

Policies

Culture

Nature

Rapid changes are happening on the top layer while change is happening at a glacial pace on the bottom. And it is this combination that gives resilience to the complete system.

It is important to remember that each layer has to respect the pace of the others.

What happened in India with the repeal of farm laws is a fascinating case study of what happens when the fast-moving technological layers don’t respect the slow nature of policy layers and infrastructure layers.

My analysis of Farm Laws so far:

Part-1: Setting the Context 🔒 | Part-2: No Country for Middle-Men | Part-3: In Defense of the Government 🔒 | Part-4: Samudra Manthan in the World of Agriculture: | Part-5: "Annadata" Conundrum" And Mapping the Cultural Wars of Agriculture 🔒 | Part-6: Can I offer you a grey pill on farm laws? | Part -7: Greta Thunberg and the aftermath of Farm Law Politics in India | My TEDx Talk on the need to dialogue in context with the farm laws.

You could very well argue that what is happening in Pakistan’s agritech scene is a classic case of attempting to build fast-moving technological layers without investment in infrastructure (gross capital formation).

What is happening in Europe and US agricultural ecosystems (in my limited understanding )could be attributed to conditions when markets are completely unfettered and unsupported by watchful policies and culture.

When we are talking of agritech, we are talking of fast layers in which we are experimenting with all kinds of marketplaces, tied with all kinds of technological innovations.

And at the same time, we are also finding out what happens when each of these marketplaces is constrained by what is happening in the slow layers.

At a time when we are seeing marketplaces that either attempt to be the exporter or provide the infrastructure platform for exporters to do exporting, we saw how the Indian government imposed a ban on rice exports to allay production anxieties and calm the prices.

At a time when there is an explosion of plant-based food marketplaces, we are also seeing how many constraints are being placed by culture, and policy layers.

If you look at the global picture, the agritech revolution is currently underway at all the layers:

Here is an incomplete snapshot view of the various ecosystems (denoted by the keyword that is driving these ecosystems). This list includes those that are top of my mind right now.

Nature - > Land Restoration, Rewilding, Food Forests, Regeneration,

Culture: Politics of Protein (Also see this), Homesteading Movement/Doomer Optimism Movement, Debates around food diets

Policies: India’s Farm Laws, European Common Agriculture Policies, COP26 (Land Conservation/Land sharing)

Infrastructure: Climatetech, Food Waste Processing, Food Parks, Energy Generation

Markets: Commodity Markets, Carbon Markets, Food Markets, Futures Markets, Trading,

Marketplaces: Well, there are lots and lots of marketplaces that are being built.

Few hours ago, I did an ‘Innovation in Agriculture’ workshop based on Pace Layers with a bunch of Indian agritech entrepreneurs at various stages of maturity.

The pace layers white board looked like this at the end of the workshop

To be an agritech player in the nick of the historical moment when we are attempting to discover what it takes to do farming in a warming planet using digital technologies is to realize the onerousness of task ahead.

We have to work across each of these six pace layers of food and agriculture systems and give our best shot. Now, if that doesn’t sound exciting, I don’t know what else is.

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Agribusiness Matters”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.

HI Venky, good newsletter as always.

I felt compelled to share a couple of things as you think about your 'stack' , the non-Ag parallels, and the pace.

- Take Ag/Food as a system, in this context its really operation, execution and becomes a series supply chain activities with operational plateaus. In this context, why do know so much about a tomato or even more about a pair of sneakers than we do about our beef supply.

- The bullet on infrastructure should be split in to digital and non-digital, while the focus is agtech, it important to be connected to the physical world that enables this.

- Finally I'd argue this is the most important component to determine pace (outside of Nature) and that is a scalable business model. A scaleable business model can be a proxy for culture, like who will adopt. A scaleable business model can be a proxy for infrastructure/technology, is it ready to enable. It can obviosuly be a proxy for markets and market places. However, its not always technology that is the great limiter but the business model. A good example is execution of data rich but people intensive activities, this is a costly no-go in North America but given labor is in high supply in lets say India, this is no longer the bottleneck.

I think its worthwhile considering those as you continue to evolve your model.

We need a packaged ecosystem solution.