Plantix and Jevons' Paradox Revisited

Can crop advisory startups fulfil their promise to reduce the inputs required for farming in India?

In 1865, William Stanley Jevons, a twenty-nine-year-old English economist, published the book, “The Coal Question”, when Great Britain was in the apogee of its military and industrial powers.

Fearing that the party might soon be over, with the country rapidly losing its coal resources, Jevons argued that James Watt's improved steam engine design, which made the coal-powered steam engine much more efficient as an energy source, led to an increase in coal consumption as the steam engine became more widely adopted by industry.

As he wrote,

“It is wholly a confusion of ideas to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to a diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth.”

Few years back, when Cloud Computing was at the peak of the hype cycle, Cloud evangelists held their head in the clouds when they proclaimed that IT budgets will reduce and will look greener, thanks to the Cloud.

What happened was something else.

As IT Researcher Simon Wardley pointed out,

“Whilst infrastructure provision may become more efficient, the overall demand for infrastructure will outstrip these gains precisely because infrastructure has become more efficient as a standardised component.”

What explains this counter-intuitive truth?

1) Price-Elasticity: Does the demand increase rapidly with the reduction in price? (And that’s why Jevons’ paradox is more applicable to energy than water consumption, as water consumption is inelastic)

2) Is there a long tail of unmet needs?

3) Are we seeing the birth of new activities?

4) Are we seeing the birth of new forms of data?

5) Are we seeing co-evolution to a higher-order system affecting both the evolution of practices (how we do something) and activities (what we do)?

If you pay attention to these questions, you could very well argue that as crop advisory startups like Plantix and Xarvio attempt to grab a share of the Indian market, what we are going to see is not a reduction in the usage of agri-inputs, but, an overall increase in the consumption of agri-inputs, as the underlying infrastructure evolves from the traditional model to a hybrid model that has digitized the necessary parts of the traditional model, without necessarily changing the underlying core tenets of the agri-input supply chain.

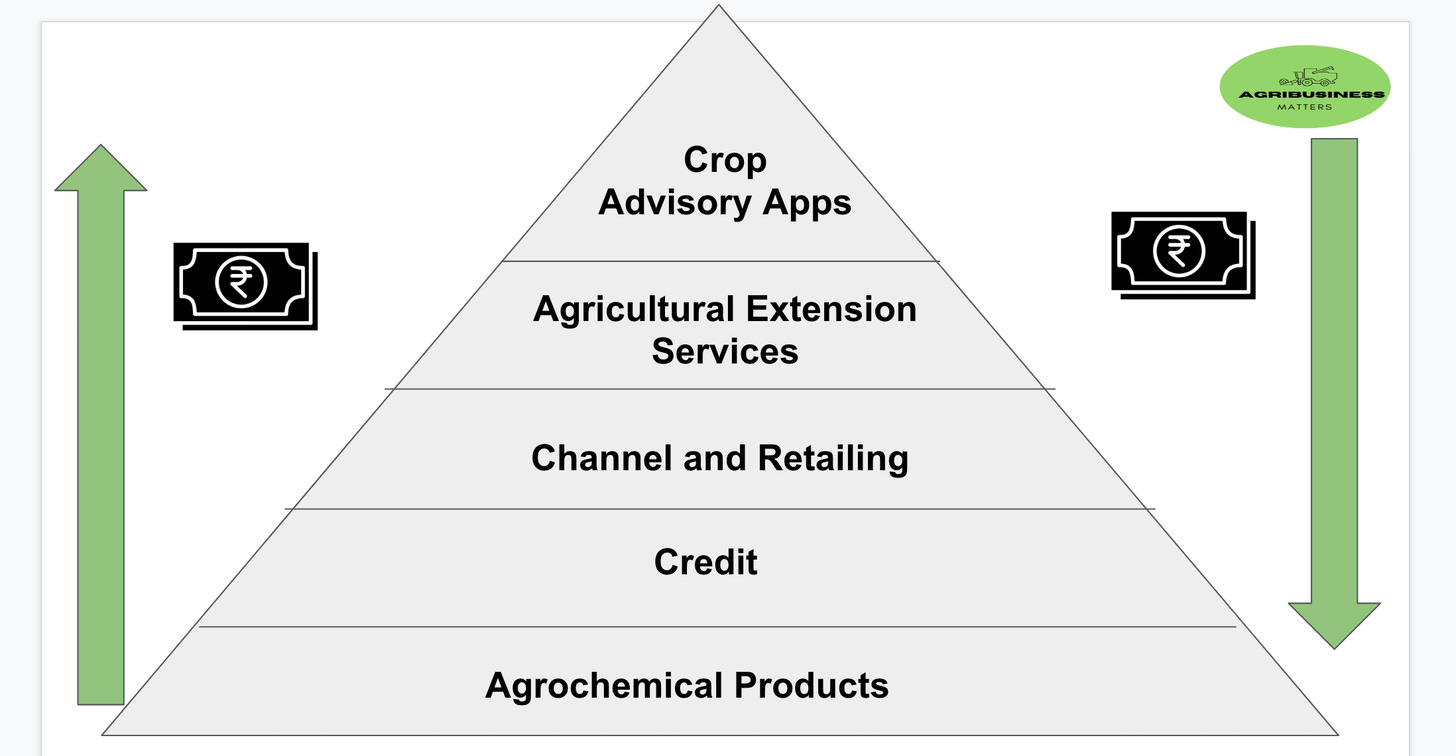

Last week, when I wrote Plantix and Two Roads to Digital Agriculture, I described the Agri-Input Hierarchy of Needs and talked about Plantix’s horizontal play, contrasting it with the vertical play of agri-input firms.

Now that Rebound effect (reduction in expected gains from new technologies that increase the efficiency of resource use) is inevitable in the case of Digital Agriculture, thanks to Jevons’ Paradox, how do we make sense of Plantix strategy?

Let’s dive in.

if you want to take Digital Agribusiness in agri-input supply chain seriously, the best place to start is the riddle posed by Betaal.

There are no easy answers to the riddle. You are going to make hard trade-offs.

This is the Digital Agri-Input Distribution Dharmasankata.

You can't serve the needs of all the three stakeholders. You have a choice to pick 2 out of 3. Whom will you pick?

You will understand this trade-off better, if you are an agri-input manufacturer.

As Jagadeesh Sunkad beautifully articulated in the discussion I facilitated on Bull-Whip Effect in Agri-Input Supply chain, what will you do when you have to produce fertilizers/pesticides all through the year, but get an opportunity to sell only in three windows (Kharif, Rabi and Summer)?

The existence of the channel in the agri-input supply chain becomes inevitable in such a case, thanks to the hyperlocal monopoly infrastructure they provide to the farmers in providing credit and agronomy support to the farmers in their respective catchment areas.

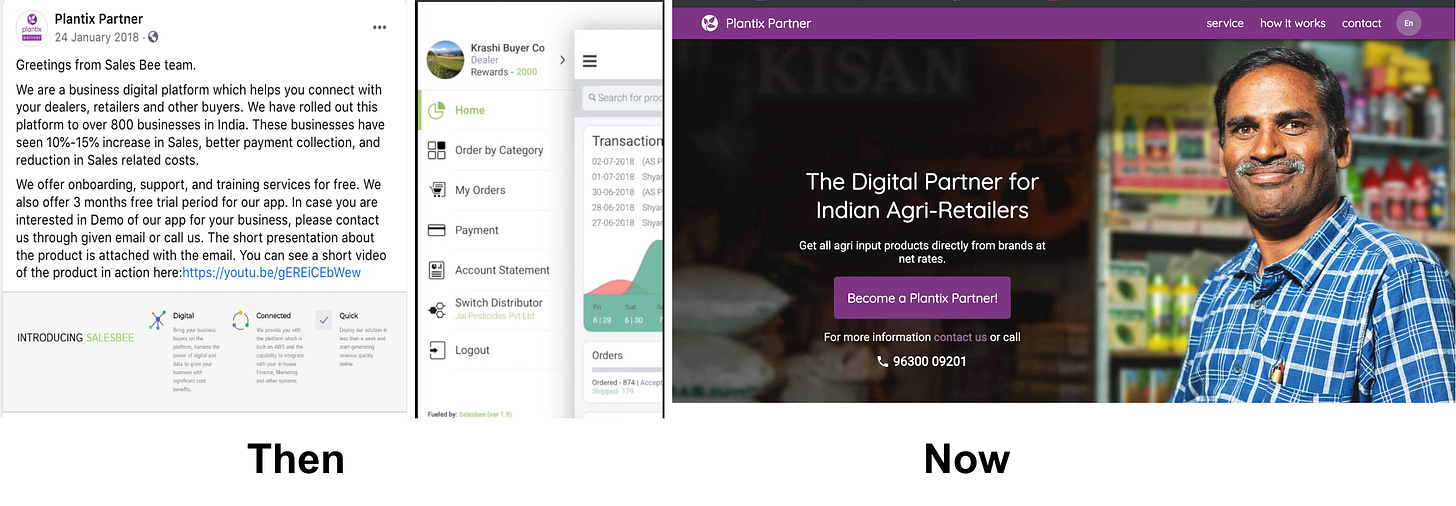

Going by their approach, it is evident that Plantix understands this well, considering the fact that they originally launched the Plantix Partner App in January 2018, not just for retailers, but also for dealers and distributors, and later, over time, smartly pivoted to focus exclusively on agri-input retailers.

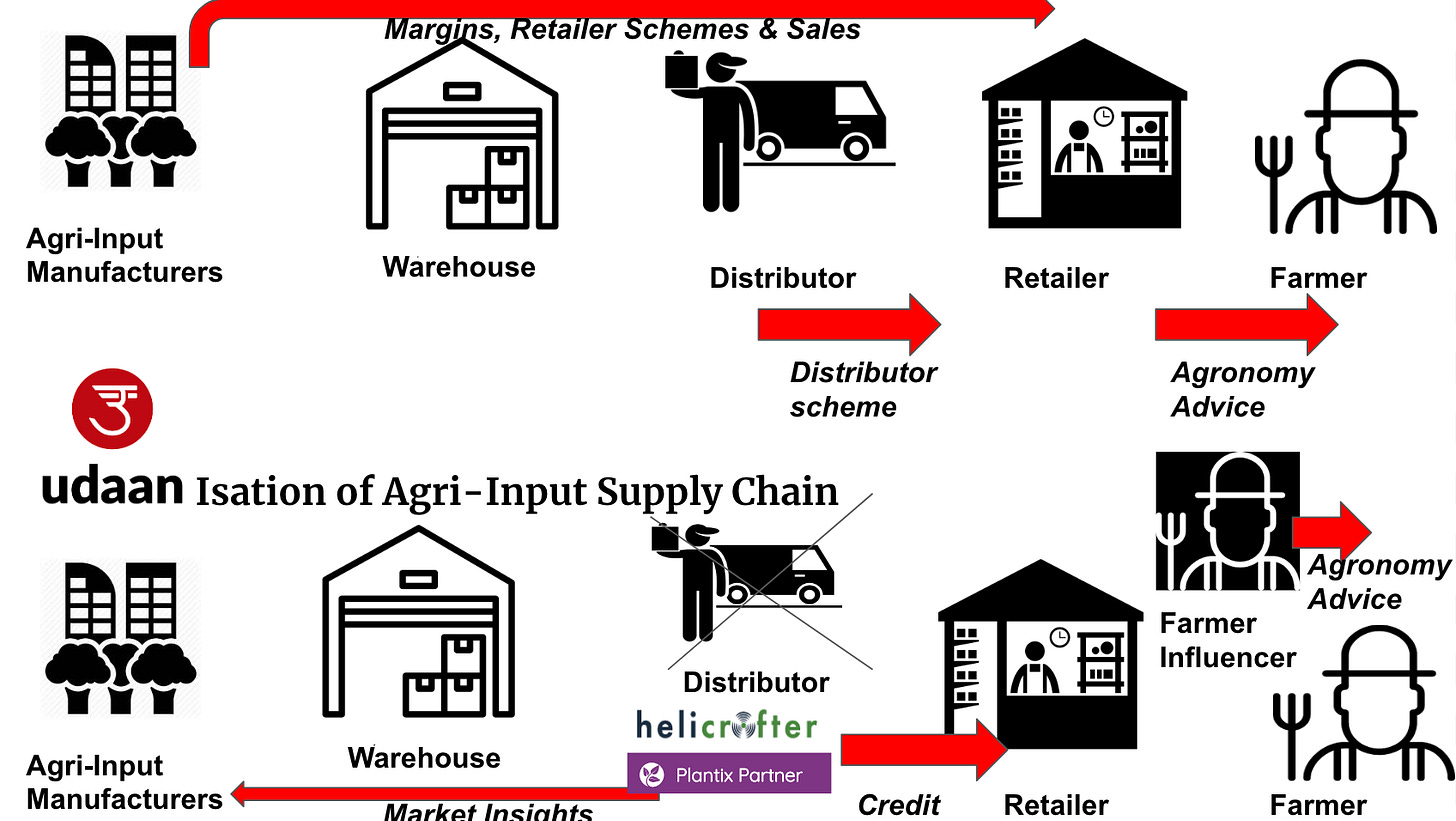

When I wrote Udaanisation of Agri-Input Retail few months back, I had observed this trend, with the birth of startups like Helicrofter, which want to do to agri-input retailing, what Udaan did to traditional mom-and-pop stores in the world of consumer products.

Of course, Udaan is also trying to get into the agricultural marketplace, and it will be interesting to see how they scale backwards and forwards, much like Agribazaar has recently done, launching their inputs marketplace, after their success of the agri-output marketplace.

What makes Udaanisation of Agri-Input Supply Chain a likely contender to shape the future of agri-input retailing are two fundamental assumptions.

Assumption-1: Traditional Agri-Input Retailers matter in the long run, as unit-economics make it impossible to serve farmers in a vacuum and ignore the complex web of relations they are enmeshed in.

Assumption-2: You can't create any long-term impact in the future of agri-input commerce without addressing the credit needs of traditional agri-input retailers.

What makes Plantix Partner similar to Helicrofter in their larger strategy approach is this: Can we disrupt the traditional distributor gameplay and go after the 10-20% of the margins that the distributor enjoy while providing access to credit to retailers and free agronomy advice to farmers?

In order to evaluate the crop-advisory startups’ gameplay, let’s contrast both the traditional and the emerging model.

Step-1: Farmer observes the plant which has been affected by the disease.

Traditional Model: Farmer goes along with the leaf/affected plant to the nearby retailer, or meets the agri-input firms’ field sales agent (who goes by the name of the extension agent, making a joke of the extension services) in his field.

Digital Model: Farmer clicks the picture of the pest and reaches out to the digital community to identify the disease and receives an automated analysis of pest and diseases

In this step, it is obvious that the digital model is far more economically efficient, as it drastically reduces the marginal cost of serving the farmers.

Step-2: Farmer receives the agronomic recommendation and is ready to make the purchase of agrochemicals.

Traditional Model: Farmer trusts the recommendation provided by the agri-input retailer with whom he has transacted for several years, buying the agri-input products on credit from the retailer, thereby de-risking his investment in his business of agriculture. Now that he has taken credit from input/output dealer, he is assured that he has offloaded the responsibility to the retailer to buy out the produce, after harvest.

You could tune into my discussion with Jagadeesh Sunkad for a deeper dive on this point.

Digital Model: Farmer reaches out to the agri-input retailer recommended, based on the geo-fencing coordinates detected by the app. The farmer now buys the product either through cash-and-carry(?) or credit sale (?) that is provided by the retailer

If you read between the lines, you would realize how much naive the digital model sounds in step 2, in contrast with the robustness of the traditional model. It throws open several questions.

1) Who is de-risking farmer’s investment through the credit sale of agri-inputs, when the farmer is matched to an agri-input retailer via an algorithm?

2) If the agri-input manufacturer is going to bear the cost of the credit that is offered to the agri-input retailer, how would the farmer be able to get the right agronomic advice that is marginally different from the incumbent traditional model, with all its flaws and unintended consequences ( Read as Bull-Whip Effect in Agri-Input Supply Chain)

3) How will the digital model disrupt the existing farmer credit equation with agri-input retailer, let alone map the existing credit inflows between the farmer and the agri-input retailer?

The key to unpacking the complexity of these questions lies in understanding the agri-input hierarchy of needs. Unless the umbilical cord that ties the agrochemical products and the credit that is offered is broken, we are only going to create incremental improvements in the name of digitization and repeat the same bull-whip effect that is prevalent in the agri-input supply chain

We will explore more aspects of the digitization of the agri-input supply chain in the upcoming editions. Stay tuned.