Saturday Sprouting Reads (Big 6 Agritech Gameplays, A No Man's Land Named Agribiotech, Monbiot's Livestock Villainy, Pre-Colonial Rural India)

Dear Friends,

Greetings from Hyderabad, India! Welcome to Saturday Sprouting Reads!

About Sprouting Reads

If you've ever grown food in your kitchen garden like me, sooner than later, you would realize the importance of letting seeds germinate. As much as I would like to include sprouting as an essential process for the raw foods that my body loves to experiment with, I am keen to see how this mindful practice could be adapted to the food that my mind consumes.

You see, comprehension is as much biological as digestion is.

And so, once in a while, I want to look at a bunch of articles or reports closely and chew over them. I may or may not have a long-form narrative take on it, but I want to meditate slowly on them so that those among you who are deeply thinking about agriculture could ruminate on them as slowly as wise cows do. Who knows? Perhaps, you may end up seeing them differently.

[Subscriber-Only]: Goliathan Agritech Gameplays

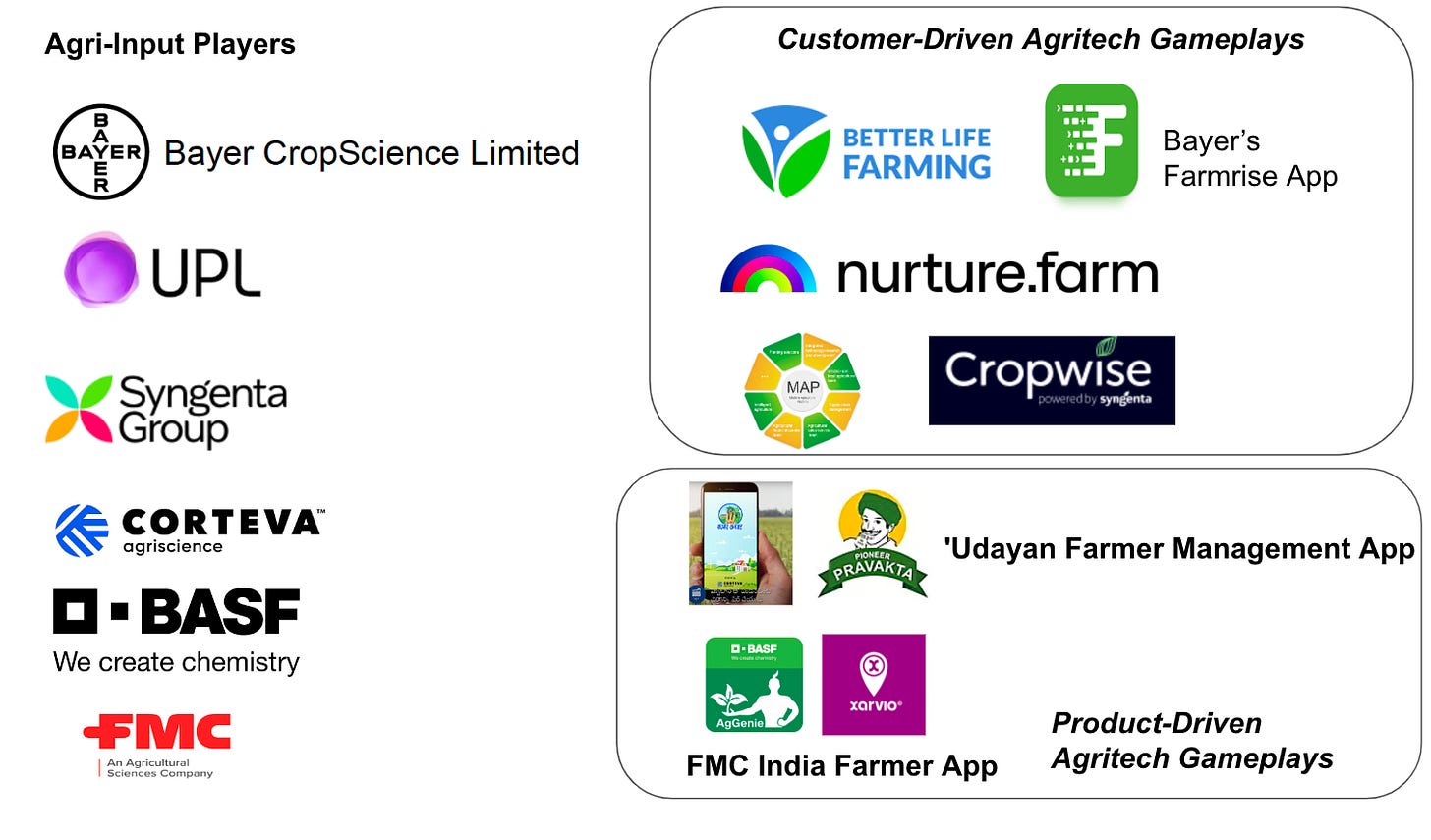

If you take a consolidated look at Indian agritech gameplays of Big 6 agri input players, you see two approaches to digital.

While Bayer, UPL and Syngenta seem to be taking a customer-driven digital approach, Corteva, BASF and FMC on the other hand, seem to be taking a more product-driven digital approach. Of these, as of now, UPL and Syngenta look promising with better digital instincts.

The difference boils down to a critical distinction between strategy and plan.

Take the recent announcement of Bayer talking of their partnership with Mastercard and Rabobank “for financial digitization of 10 million smallholder farmers in India”. While it is replete with several “digital transformation” initiatives (Bayer’s Better Life Farming, Value Chain Partnerships) and platforms (Master Card’s Farm Pass, Bayer’s Farm Rise), I don’t see the clarity of strategy with an “integrated set of choices”, to use Roger Martin’s words, that positions Bayer to win.

As I had mentioned in my earlier ($)analysis of Bayer Vs UPL, to be fair to Bayer, they had been following a micro-services approach (in contrast to a monolith) in an agritech ecosystem that is way too nascent for micro-services.

Now contrast this with UPL’s recent announcement to include insurance coverage for farmers who purchase Advanta’s Okra seeds. There is only one platform in the picture (nurture.farm) in which each of these capabilities is being added incrementally over time.

Even if you argue that platforms in agritech contexts are only vaporware ( as in, platforms are mere wrappings to make it look sexy and cool, while real transactions are happening offline), this monolith approach is extremely important if you think of digital strategies as a set of building meshed flywheel gears that eventually adds up to create a strong moat.

In this subscriber-only post, I dig into each of the Big 6 agri-input firm’s agritech gameplay and examine its possibilities and limitations.

[Subscriber-Only]: A Study of Agriculture as if Climate Change Mattered - A Dialogue with Sameer Shisodia

Venky: “Let’s make this real. Your farm is in Coorg. Imagine a farmer who is in Coorg and, for the sake of this conversation, let us imagine that he is completely convinced of the need to change. What would be the kind of trade-offs that he would be doing in that ideal scenario? I'm framing this from the sense of a farmer so that we get a better sense of how it impacts us as well. I'm not saying that they alone have to change. From a farmer's perspective, what are the kind of trade-offs that he or she would do differently?

Sameer: “I am going to go a little deeper. And this is almost the core of our thesis, in some sense.”

“If you take a farm, it's a unit of the planet-the planet is basically made of millions of such units or billions of such units. That's what it is. So when we say that the planet is unsustainable today, we have a crisis, it means that a few variables have gone off. You are right now sitting at your home having this conversation with me comfortably, because, the family's health is all right, there's electricity at home, there is some source of income, and the air you are breathing is breathable to a decent extent, there is water supply, nobody is breaking your door down and trying to get in, and a bunch of such variables, people are in harmony, there's no major anchor, otherwise you would have stopped this and attended to that. It's a bunch of variables. You didn't calculate it, you didn't measure it but you have your sense of the house.”

“Our sense of the house, at the level of the farm, village, city, the planet is broken.”

“We have optimized on one or two variables at a time. I'm not just talking about money. When we go and try to solve water, we solve water, but we accrue a debt in energy, when we solve income, we accrue a debt in livelihoods- we actually reduce the number of livelihoods in trying to expand the income. Today, a village has hardly any livelihoods left. If you ask anybody in policy, anybody in the city, if you ask most people in the village, a village is, by default, farming. A village has no production capacity beyond farming. And this was not true. My last visit to the tribal museum in Orissa was very telling. They had metallurgy, exquisite work in fabric and weaving, woodwork, you name it, they were basically producing stuff for themselves. Not necessarily in one village. In a sub-region, there were skills of all kinds.”

A No Man’s Land Called Agri-Biotech

Those who study agriculture do not study the core of life sciences. They end up reading applied sciences such as cropping, and agronomy. Who is out there to teach biochemistry, physiology, and chemistry that is needed to come up with innovations in agrifood life sciences?

And what about those plant biochemists and physiologists who come up with real solutions but don’t know how to take them to market or worse unable to diagnose if their solution is marketable in the first place?

No wonder, investment activity is paltry in India, when compared to its global counterparts.

Considering where the US, China and the rest of the world are in driving innovations in agrifood life sciences to feed the world on a warming planet, we need to bring in interdisciplinary thinking to incubate startups, provide them with relevant infrastructure and more importantly, address the albatross of “functional fixedness” that comes with outdated academia mindsets.

Monbiot’s Livestock Villainy

With voices concerned about Climate Change getting shriller, we are seeing early glimpses of eco-fascism across the world that exploit the clash of paradigms unfolding in global agriculture for vicious means.

Take the case of the Dutch Government announcing its intent to close 3000 farms, setting aside €24.3 billion as compensation for the planned seizure and closure of private property, to comply with EU rules to halve its nitrogen emissions by 2030.

Or take the case of George Monbiot who has been advocating the death knell of animal agriculture in his books (Regenesis) and in his social media feeds.

I am not the kind to get riled by acerbic tweets that sacrifice truth’s grey shades for brevity, but this one got my goat.

I can only reasonably suppose George is only talking of the Global North and not countries of the Global South like India, which has the best livestock model in the world.

While there is plenty of literature to rebut these reductionist claims, when I look at their underpinning premises, I see an intriguing pattern that points out the limits of quantification in understanding a complex domain like agriculture.

Let’s start with this graph. Can you point out what is the flawed assumption behind this graph put together by Hannah Ritchie?

Greenhouse gas emissions per kilogram of food product?

In a domain that is notorious for cheap food, measuring greenhouse gas emissions per kilogram of food output, instead of calories, is the best prescription to develop a myopic vision in our understanding of food and agriculture.

Insisting that ‘rural’ be kept artificially separate from ‘urban’, ‘land sparing’ be kept artificially separate from ‘land sharing’, and ‘microbes’ be kept artificially separate from the ‘food’ we consume, is the surest way to miss the forest for the trees.

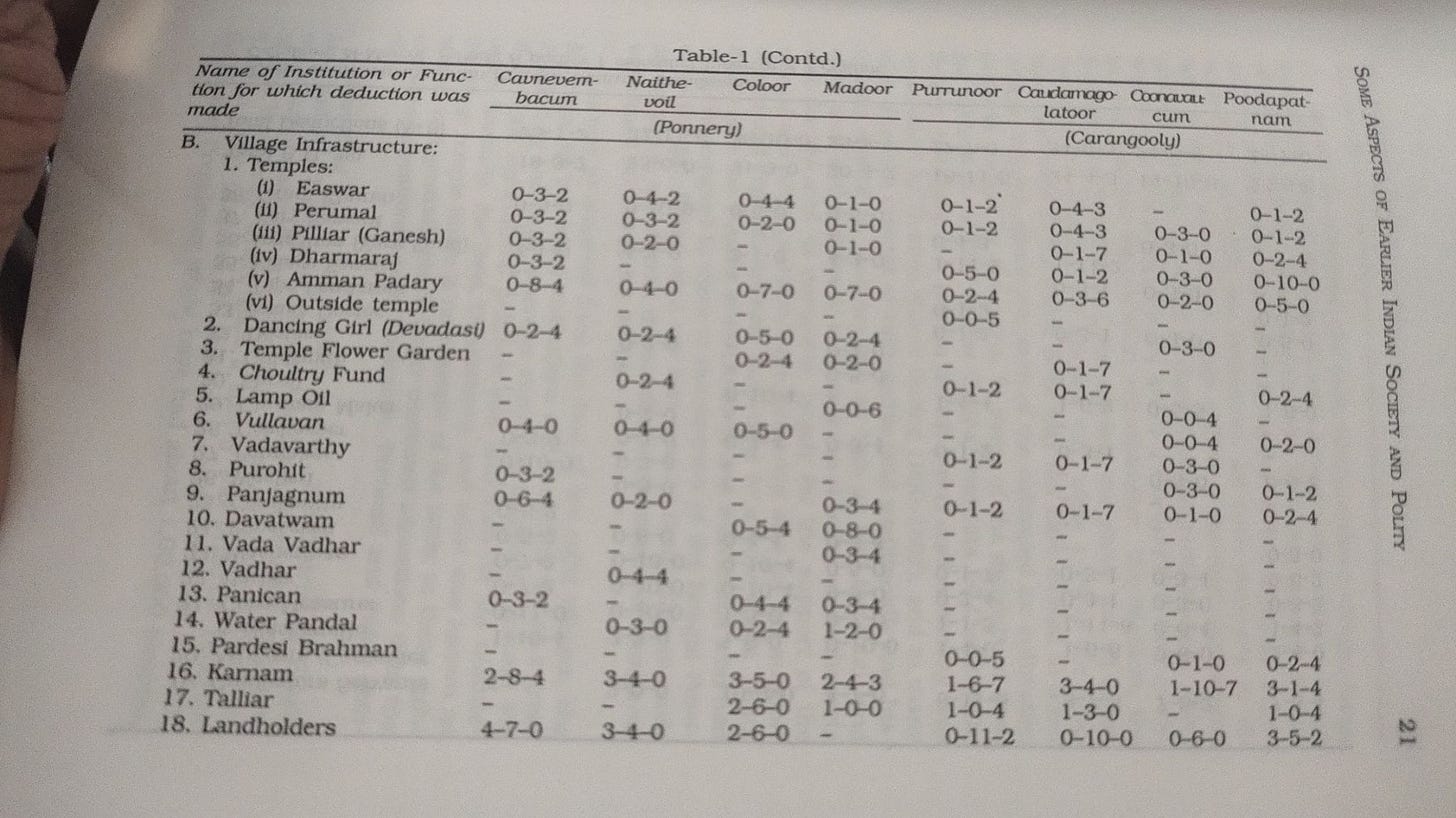

Dharampal and Pre-Colonial India

I have been reading Dharampal's works (who started researching pre-colonial India from the British archives upon Mahatma Gandhi's request) and these data points gathered from survey data of the 1770s for a few south Indian villages blew my mind.

It shows how vibrant rural India was.

The survey data from South Indian villages circa the 1760s and 1770s details how much deductions were made from agricultural produce for the maintenance of various institutions and infrastructures of the villages.

Not many understand that the vision of rural India Gandhi painted in his 1909 small booklet,' Hind Swaraj', is based on his deep understanding of pre-colonial India and the underlying framework which organised its society and polity.

Here is the most fascinating bit.

Today, if you talk to complexity researchers/designers like John Thackara or anyone who is talking about 'bio regionalism’ or anyone seriously concerned about redesigning our social and food systems in the wake of climate change, at the heart of it, you will see that what they are saying now in 2022 is almost similar to what Mahatma Gandhi wrote in 1909.

Here is the thing: The point is not about nostalgia towards the past. Can we draw inspiration and build local, resilient food systems and underlying bioregional economies in 2022 in today’s context? We will find out.

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Agribusiness Matters”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.