Saturday Sprouting Reads: Crouching Dragon, Dancing Elephant

Whenever economists want to talk about farmers exiting farming without sounding offensive, they talk about structural transformation. Can China and India pull off Structural Transformation?

Dear Friends,

Greetings from Hyderabad, India! My name is Venky and I write Agribusiness Matters. Welcome to Saturday Sprouting Reads!

About Sprouting Reads

If you've ever grown food in your kitchen garden like me, sooner than later, you would realize the importance of letting seeds germinate. As much as I would like to include sprouting as an essential process for the raw foods that my body loves to experiment with, I am keen to see how this mindful practice could be adapted for the food that my mind consumes.

You see, comprehension is as much biological as digestion is.

And so, once in a while, I want to look at one or two articles or reports closely and chew over them. I may or may not have a long-form narrative take on it, but I want to meditate slowly on them so that those among you who are deeply thinking about agriculture could ruminate on them as slowly as wise cows do. Who knows? Perhaps, you may end up seeing them differently.

Programming Note: I missed sending last week’s edition of Saturday Sprouting Reads. I hope you missed it as much as I did:)

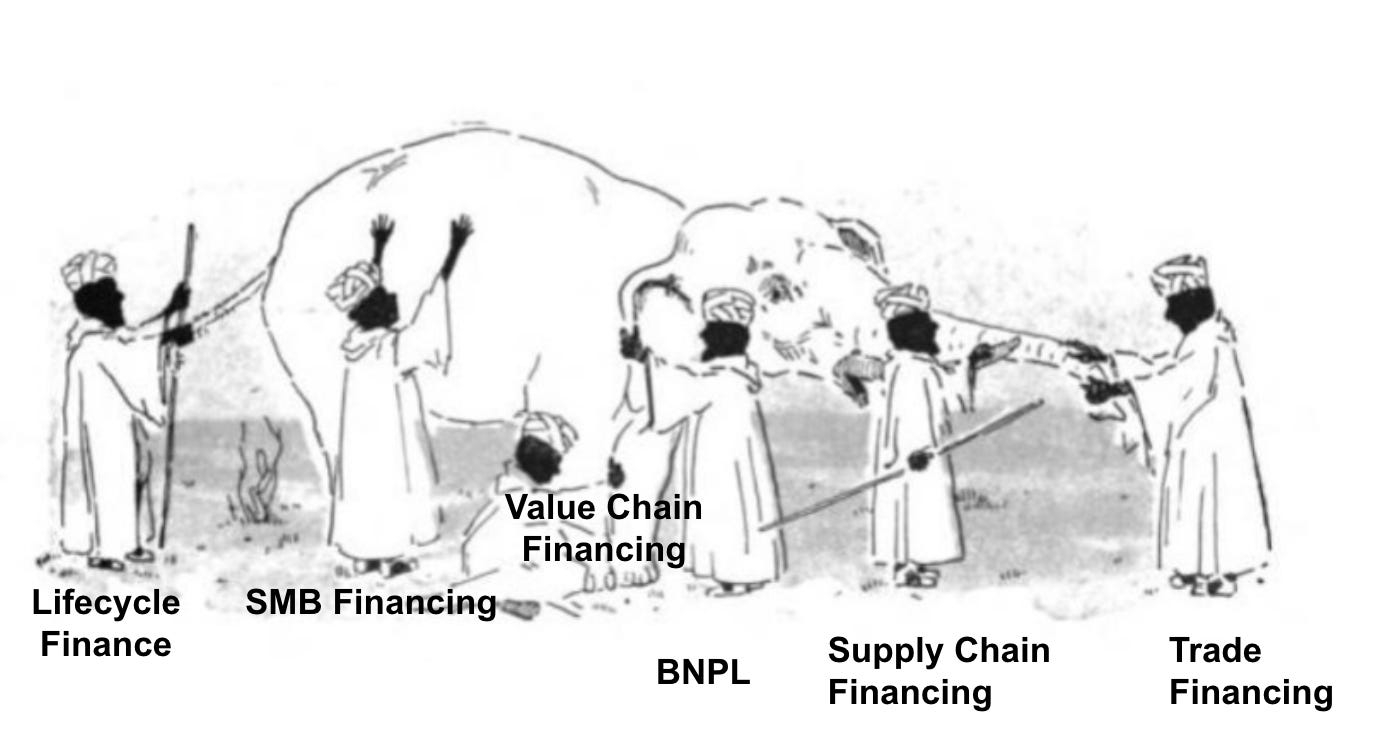

[Subscriber-Only] Blind Men and the Elephant called Rural Finance

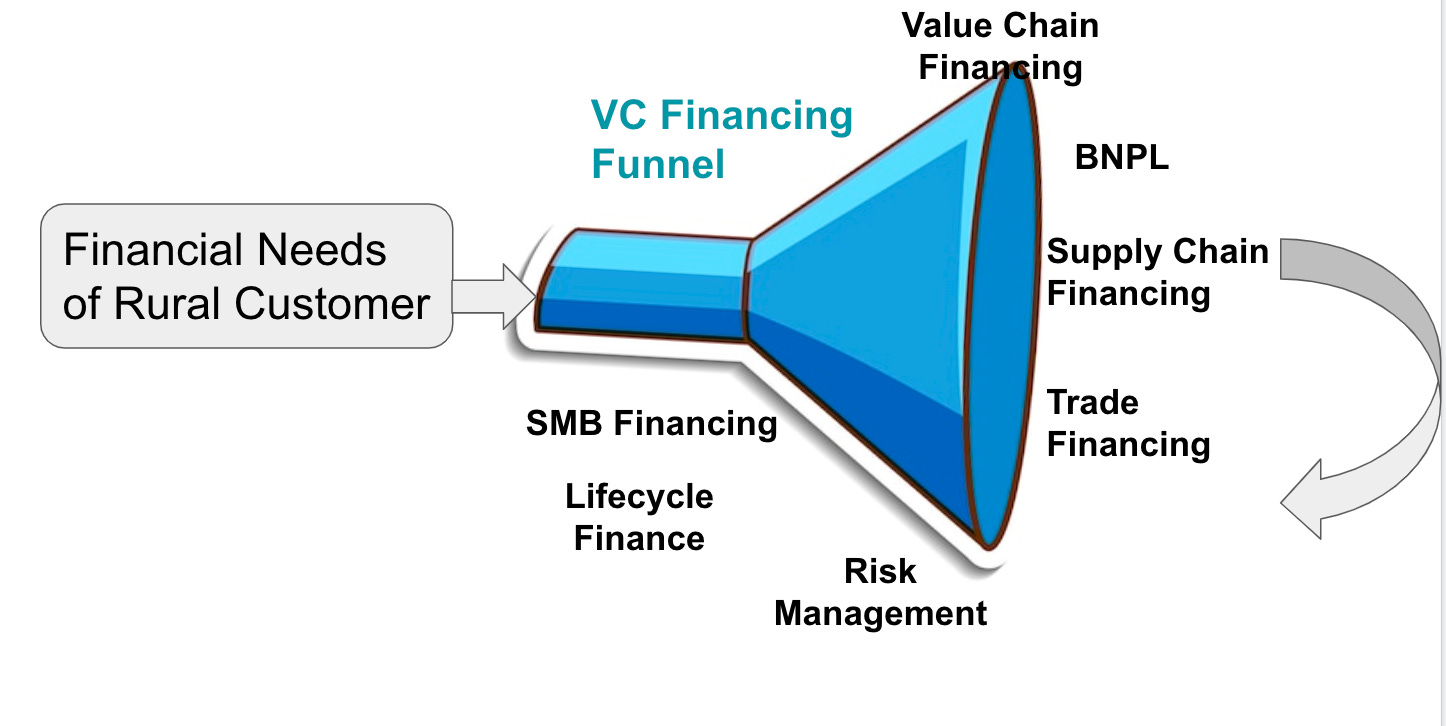

Last week, I was on an investor due diligence call for an agrifintech startup. In my futile attempt to explain to him the complexity of the rural finance landscape, I discovered an obvious truth about the feedback loop of VC financing. The feedback loops in my head roughly look like this.

The ones on the output side of the funnel have survived the VC financing acid test. The ones in the periphery have either partially succeeded or failed.

Of course, not all financing workflows have to go through the VC financing funnel. However, the ones that tend to go through have a tendency of cannibalizing those that cannot. Last week, I spoke of how agrifintech platforms are eating agritech platforms ($) in order to keep the VC funding pipe active.

If you zoom in, what is really happening underneath is this.

Financing workflows which successfully go through the VC financing funnel quickly spread like memes. When that happens, vertical agritech platforms, alongside horizontal rural tech platforms start replicating those VC fundable workflows while building newer and differentiating capabilities on top of them.

In this subscriber-only post, I dig into how Jai Kisan's offerings changed from their 2021 $30 Mn Series-A round to the 2022 $50 Mn Series-B round, how Gramophone attempts to be the Meesho of Indian Agriculture, how horizontal and vertical models look in agrifintech and more.

[Subscriber-Only] Can Syngenta build Modern Agriculture Platform (MAP) for smallholding countries?

Syngenta India HQ recently organized a digital strategy workshop with some of India’s leading agritech startups. Given Syngenta Group’s $10 Billion Shanghai IPO Plans, what could be their global agritech gameplay?

As an analyst, one of the things I try and do is to connect the dots and see what could unfold. This article is also my attempt to track China's agritech ecosystem to the extent possible.

These are challenging times, with China in the middle of a record-breaking heat wave, while facing heat over their slow growth performance and sluggish domestic consumption. Can China drive digital agriculture ahead with their red revolution approach through Syngenta's Modern Agriculture Platform?

Crouching Dragon, Dancing Elephant

When Amartya Sen explored what China could teach India then and now, many moons ago, he wrote,

“In 7th century when Xuanzang left India and went back to China after having spent about a decade in India, he asked rather implausibly the question, 'Is there anyone in India who does not admire China fully?' This is the nice 7th-century question. It is a serious question and of course, it is coming in many different forms."

When you contrast India and China’s tryst with ‘Structural Transformation’, this 7th-century question could very well acquire a different meaning and possibly change stripes.

Both are standing at similar crossroads, with India having 928.3 million working-age (working age 15-64) people, while China has 1 Billion working-age people by 2020.

By 2040 though, the lottery of demographic advantage will favour India more than China. If you go by UN statistics, India will have a 1.09 billion working age, while China shrinks to 989 million, with the fertility rate expected to decline further than what those UN numbers suggest.

Where do China and India stand in their tryst with structural transformation?

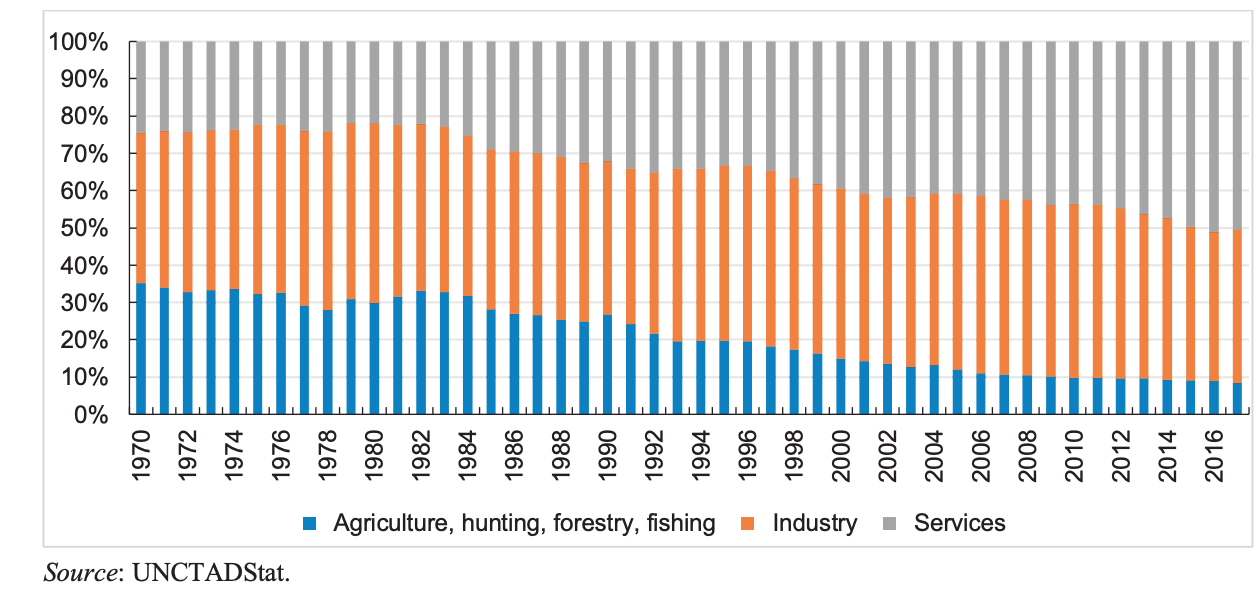

“In early 2021, China announced that it has eradicated extreme poverty based on the national poverty line. Pulling millions of people out of poverty was accompanied by other structural transformation indicators, including the declining agriculture, forestry, and fishing value-added as a percentage of GDP from 27 per cent in 1990 to 7 per cent in 2019”

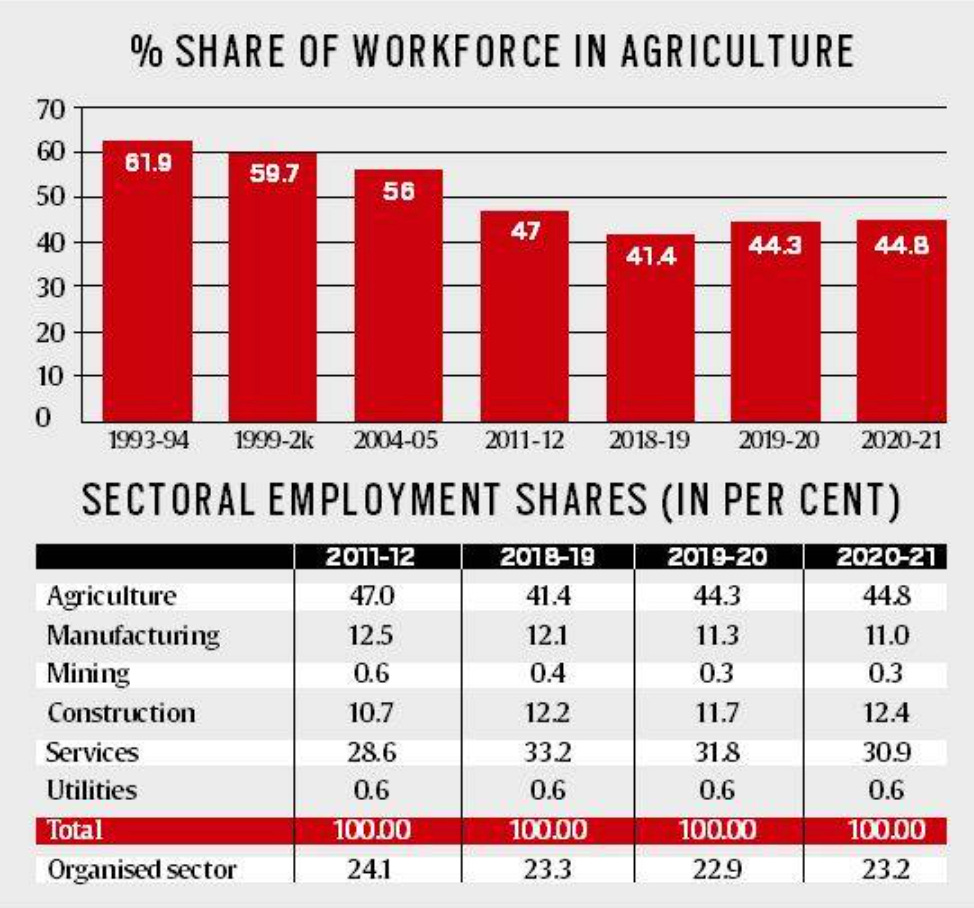

“Overall, between 1993-94 and 2018-19, agriculture’s share in India’s workforce came down from 61.9% to 41.4% (see chart). In other words, roughly a third in 25 years. That isn’t insignificant. Basole estimates that given its level of per capita GDP in 2018 – and compared with the average for other countries in the same income bracket – India’s farm sector should be employing 33-34% of the total workforce” - Explained, India’s Unique Jobs Crisis

But that doesn't explain why there has been an increase in the number of people joining agriculture for employment in the case of India. Does it?

“The CMIE analysis says that the share of the agriculture sector in total employment has increased to 45.6 percent in 2019-20, from 42.5 per cent in 2018-19.” - Periodic Labour Force Survey 2019-20

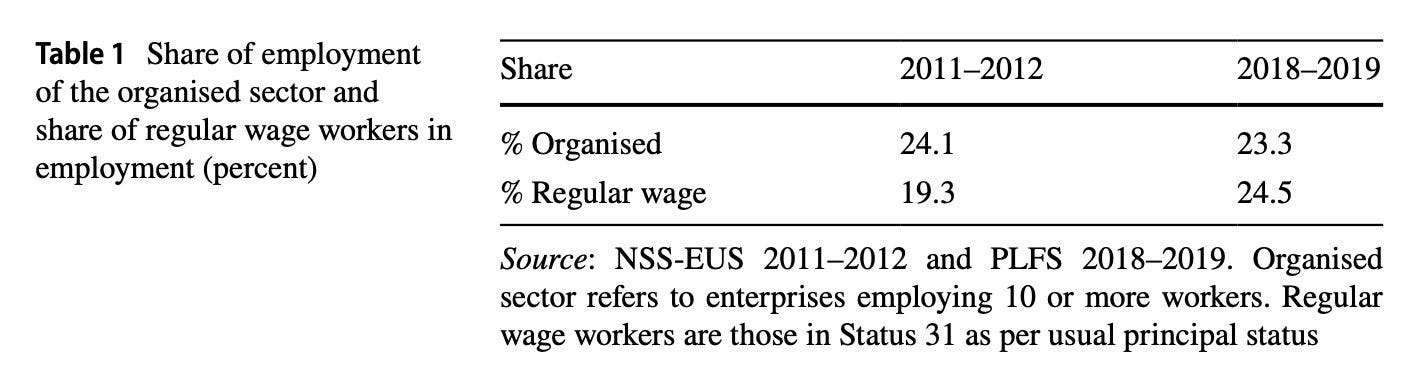

Typically, when economists talk about structural transformation, they talk of the labour force moving from lower-productivity activities (agriculture) to higher-productivity activities (manufacturing and services). In the case of India, it’s plainly obvious that it hasn’t happened. Only 23% of the Indian workforce work in enterprises employing 10 or more workers.

What about the rest?

They are working either as migrant labourers in India or abroad. As Harish Damodaran points out, “the bulk of the jobs… are in petty retailing, small eateries, domestic help, sanitation, security staffing, transport and similar other informal economic activities.”

This partly explains why smallholding farmers are holding on to their small plots of land, even though they may be earning their livelihoods from other informal economic activities, as it gives them the security that the informal, precariat sector doesn't give.

Mind you, this feedback loop further viciously affects the profitability of Indian Agriculture by making labour costs unviable for farmers who continue to farm.

Few days back, I visited farmers, scientists, agricultural extension officers, and rural bankers at Jammikunta Krishi Vigyan Kendra and Mulkanoor Cooperative Rural Bank in the southern state of Telangana in India.

Farmers shared how they are now expected to give a quarter of liquor (for men) and thumbs up (for women) along with labour costs to attract them to work in their fields.

Based on the anecdotal observations and discussions, it seems that only when a farmer owns 5 acres or more, provided he has an irrigation facility, his family is working (and offering free labour) on the land and he owns a tractor, he can make make agriculture profitable.

In other words, it is much more lucrative to be a labourer than a farmer and get stuck in an eternal debt trap.

And so, if you step back and understand the linkage between agricultural profitability and structural transformation, the central problem is this, as neatly articulated by Sridhar Vembu in a recent lecture.

The value of agricultural production alone is insufficient to pay for all the manufactured rural citizens want and need.

The nature of the structural change in the case of China and India couldn’t be more different.

As Shenggen Fan and Ashok Gulati put it in their 2008 paper, “China started off with reforms in the agriculture sector and in rural areas, while India started by liberalising and reforming the manufacturing sector."

However, both have to pursue a dual strategy of leveraging technologies to make agriculture pursued by small-scale farmers profitable while encouraging the rest to leave agriculture and pursue job opportunities outside agriculture.

Given India has a demographic advantage (which China doesn’t) , when the bulk of this transition happens, India might have an edge, due to its larger younger population who might be better placed to train and adapt to non-agricultural sectors.

What will a bull case and bear case look like? We will explore further.

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Agribusiness Matters”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.

Great one