Saturday Sprouting Reads: 'Luxury Beliefs' and Limits to Growth in Food and Agriculture

If you are feeling sunny this weekend, play tennis or watch movies. Don't read further. I bring some old bad news.

Dear Friends,

Greetings from Hyderabad, India! My name is Venky and I write Agribusiness Matters. Welcome to Saturday Sprouting Reads!

About Sprouting Reads

If you've ever grown food in your kitchen garden like me, sooner than later, you would realize the importance of letting seeds germinate. As much as I would like to include sprouting as an essential process for the raw foods that my body loves to experiment with, I am keen to see how this mindful practice could be adapted for the food that my mind consumes.

You see, comprehension is as much biological as digestion is.

And so, once in a while, I want to look at one or two articles or reports closely and chew over them. I may or may not have a long-form narrative take on it, but I want to meditate slowly on them so that those among you who are deeply thinking about agriculture could ruminate on them as slowly as wise cows do. Who knows? Perhaps, you may end up seeing them differently.

[Subscriber-Only] Is Organic Food a Luxury Belief for the Privileged?

Considering all the data and the information I have access to, I have come to a harsh conclusion:

Organic food is now a "luxury belief" among the privileged rich who are now obsessed with talking so much about synthetic chemicals inside food, without realising how badly the economics is stacked against the farmer to grow food in the first place and gain a penny more, leave aside safe food (and genuine concerns one may have about safe food)

Pay attention to the operating word.

B-E-L-I-E-F

What is a luxury belief?

In the good old days, status-seeking apes (read as humans) showed our status with luxury goods. Today, now that China has made the idea of luxury goods redundant, we flaunt our privilege with "luxury beliefs".

In the words of Rob Henderson who coined it, they are "Ideas and opinions that confer status on the rich at very little cost, while taking a toll on the lower class".

When I look at the sleek packaging and brand positioning of D2C organic food brands that have mushroomed after the pandemic, this becomes obvious.

In case you haven’t noticed, there is now a playbook to sell packaged organic food products to reward consumers with the privilege of being stewards of the planet and saviours of the farmers.

Package the food with a knapsack or with imagery and symbolism that make the food look rustic, earthy and trustworthy.

Write a personalized handwritten note inside the packaging that assures customers of the good sustainable consumer choice they have made for the planet by purchasing organic food. Show them ways to participate in this movement forward.

Put a photo of a farmer standing with a heart chock full of gratitude.

Put a QR code which gives all information other than what is needed - an insight into how the farmer grew the food in the first place. What were the cropping practices?

In this subscriber-only post, I dig into the data that makes me conclude why organic food is largely a luxury belief, the D2C organic food brand marketing playbook and how to address the question of trust versus certification in traceability systems for food and agriculture.

Limits to Growth in Food and Agriculture

In April 1968, a motley group of scientists, intellectuals, industrialists and civil servants came together to form an informal group called “Club of Rome”, sharing a deep concern for ‘the long-term future of humanity and the planet’.

They convened a meeting in Bern, Switzerland and Cambridge, Massachusetts in the summer of 1970 to discuss the ‘predicament of mankind’.

Under the expert guidance of Jay Forrester (whom we met when I talked about bull-whip effect in agriculture), a team of researchers, including the famous professor Donella Meadows (whom we met when I wrote “Seven Lessons from Dancing with Systems of Food and Agriculture”), published a highly influential book in 1972 titled, “Limits to Growth”.

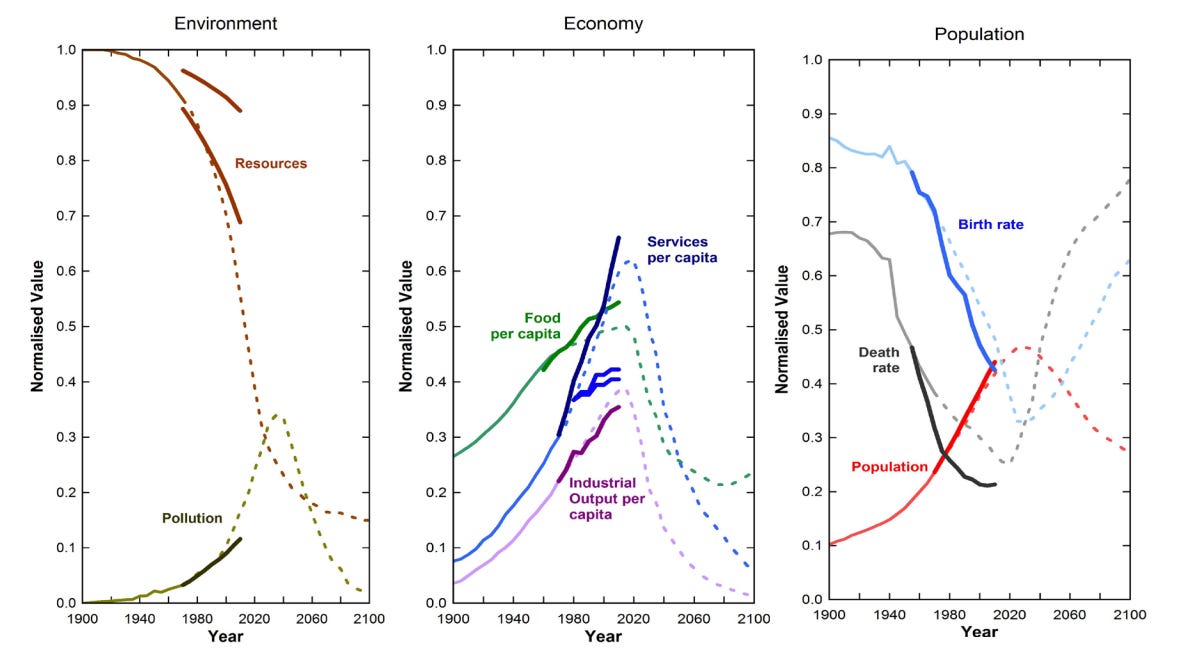

Essentially, the research was built on the famous World3 computer model (birthing the nascent domain of System Dynamics) that showed how five fundamental factors of our civilization interact with each other (thanks to this magical phenomenon called exponential growth) and ultimately, limit the growth of the planet.

Population.

Agricultural production.

Non-renewable resource depletion.

Industrial output.

Pollution.

The model outlines 12 scenarios and funnily enough (of the black kind) all scenarios end up in the collapse of civilization by 2100.

In 2000, investment guru Matthew R. Simmons published a paper titled “Revisiting The Limits to Growth: Could The Club of Rome Have Been Correct, After All?

Assessing the predictions, he wrote,

“For a work that has been derisively attacked by so many energy economists, a group whose own forecasting record has not stood the test of time very well, there was nothing that I could find in the book which has so far been even vaguely invalidated.”

In 2014, Dr. Graham Turner updated the model with the latest data that was available and plotted them alongside the “Business As Usual” scenario mentioned in the book.

He found that the model is on track with reality.

“It is evident …that the data generally aligns strongly with the BAU scenario (for most of the variables); while the data does not align with the other two scenarios (Turner, 2012, Turner, 2008)”

In 2021, Gaya Herrington further updated the data and concluded

“From these graphs and two quantitative accuracy measures, I found that the scenarios aligned closely with observed global data, which is a testament to the LtG [Limits to Growth] work done decades ago. The two scenarios aligning most closely indicate a halt in growth over the next decade or so, which puts into question the usability of continuous growth as humanity’s goal in the 21st century.”

When I am looking at the developments happening in global food and agricultural systems in 2022, I feel compelled to assume that the model’s predictions which were made fifty years ago, will likely come true in the next fifty years.

Supply chain crises have become the norm and businesses are in knee-jerk reaction mode, leading to an inevitable cycle of short-term glut followed by long-term scarcity.

Food prices are skyrocketing. FAO predicts that 46 countries (33 from Africa, 10 from Asia, and 2 from Latin America) will need food assistance.

“Unlike any time in recent history, India is facing double-digit inflation rates at the wholesale level for two consecutive years (since April 2021). In June 2021, wholesale inflation rate was already 12.1 per cent. Inflation rate of 15.2 per cent in June 2022 builds on this higher base.” (Source)

And if you remember, we witnessed something similar during 2007-08 (which was blamed on “excessive speculation” )and subsequently during 2010-12.

In case you are unable to see the forest from the trees, what these disparate data sources are pointing out is this

Cheap food will become an old relic. As food prices skyrocket, countries with surplus will disconnect from the global food supply chain ( 21 countries including India have export bans) to feed their population and prevent the kind of disasters we saw unfold in Sri Lanka.

As I am writing this, I hear a mental voice probably from some of you reading this.

“Wait a minute. You are cherry-picking research that neatly validates this foregone conclusion. What data have you independently found that could validate or invalidate this?”

Fair point.

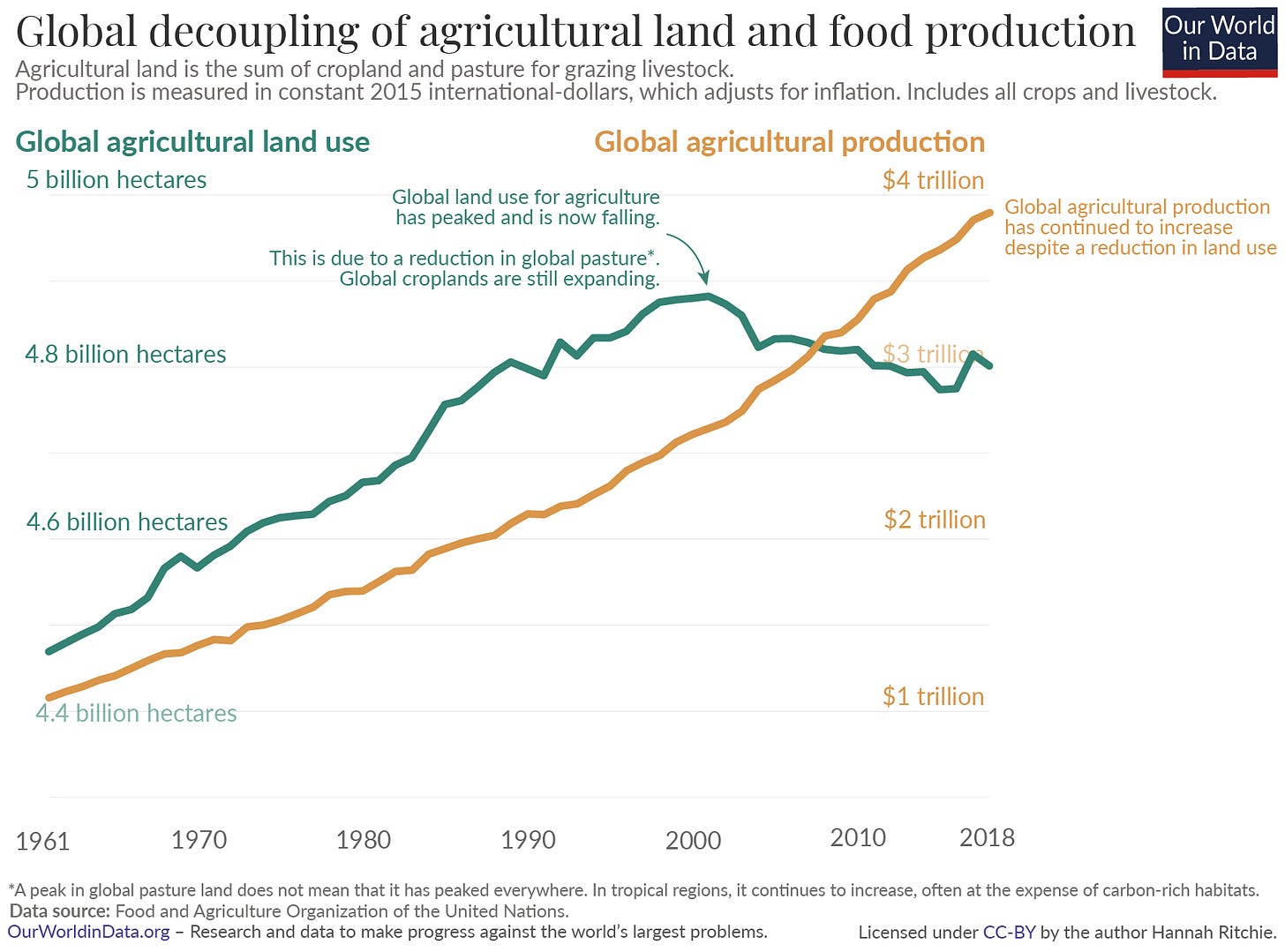

I did find data points that might challenge some parts of the argument in the book. Central to the argument of the book is decoupling physical growth and economic growth. While it is plainly obvious that we haven’t done so globally, in the case of food systems, one could argue against this to an…extent.

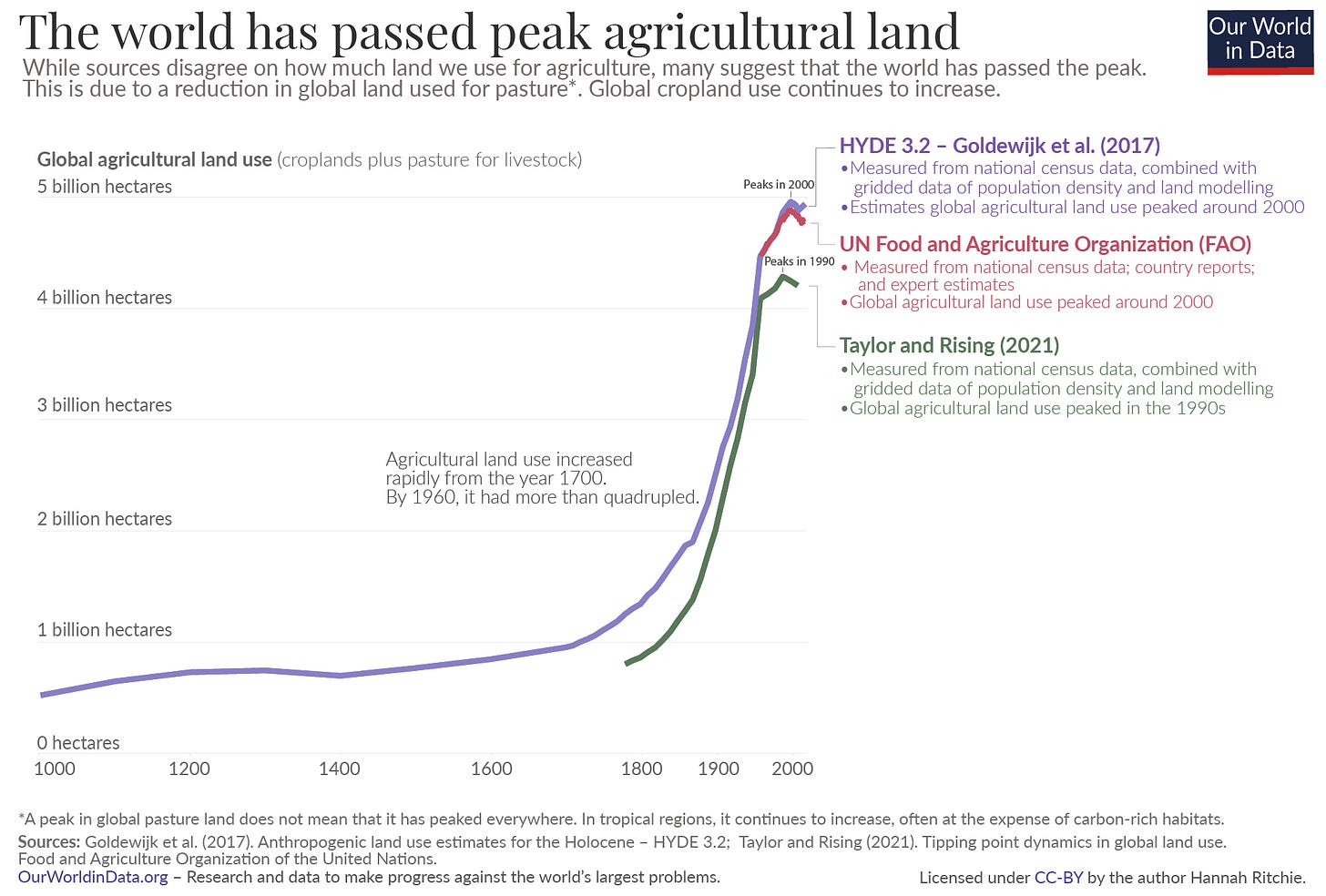

Three different data sources claim that the world passed peak agricultural land use around the 1990s and 2000.

However, there has been a decoupling of agricultural land and food production.

“While global agricultural land – the green line – has peaked while agricultural production – the brown line – has continued to increase strongly, even after this peak.” (Source)

This naturally comes with a price tag of environmental stresses. If you are able to read between the lines of the argument posed by Hannah in this article, it follows the mainstream false binary of land sparing and land sharing.

How do we combine agricultural production-producing food, fibre and biomass- and biodiversity conservation simultaneously in the lands we have got is now the real challenge that confronts us if we are serious about “Limits to Growth” in our food and agriculture system.

Pursuing this question gives me 1% optimism. And that is more than enough to continue writing this newsletter:)

We will explore this further.

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Agribusiness Matters”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend