Sprouting Reads #3: Jagadeesh Sunkad on Farmers' Share of Consumers' Price

We've always dreamt of bridging the economic, cultural, and psychological chasm between farmers and consumers. Is it possible? Why don't we ask a different question: Is it necessary?

Dear Readers,

Welcome to the third edition of Sprouting Reads.

You can check out the previous editions here.

Sprouting Reads #1: Amitabh Kant's Agritech Oped, Jain Irrigation's Recast Plan & India's Edible Oil Problem.

Sprouting Reads #2: TCA Ranganathan's Opinion on Farms and Cities

About Sprouting Reads

If you've ever grown food in your kitchen garden like me, sooner than later, you would realize the importance of letting seeds germinate. As much as I would like to include sprouting as an essential process for the raw foods that my body loves to experiment with, I am keen to see how this mindful practice could be adapted for the food that my mind consumes.

You see, comprehension is as much biological as digestion is.

And so, once in a while, I want to look at one or two articles closely and chew over them. I may or may not have a long-form narrative take on it, but I want to meditate slowly on them so that those among you who are deeply thinking about agriculture could ruminate on them as slowly as wise cows do. Who knows? Perhaps, you may end up seeing them differently.

Jagadeesh Sunkad on Farmers’ Share of Consumers’ Price:

Jagadeesh Sunkad has been one of my dear friends and mentors and I take his word very seriously. Ever since I read his recent article on farmers’ share of consumer price, I have been thinking deeply about it.

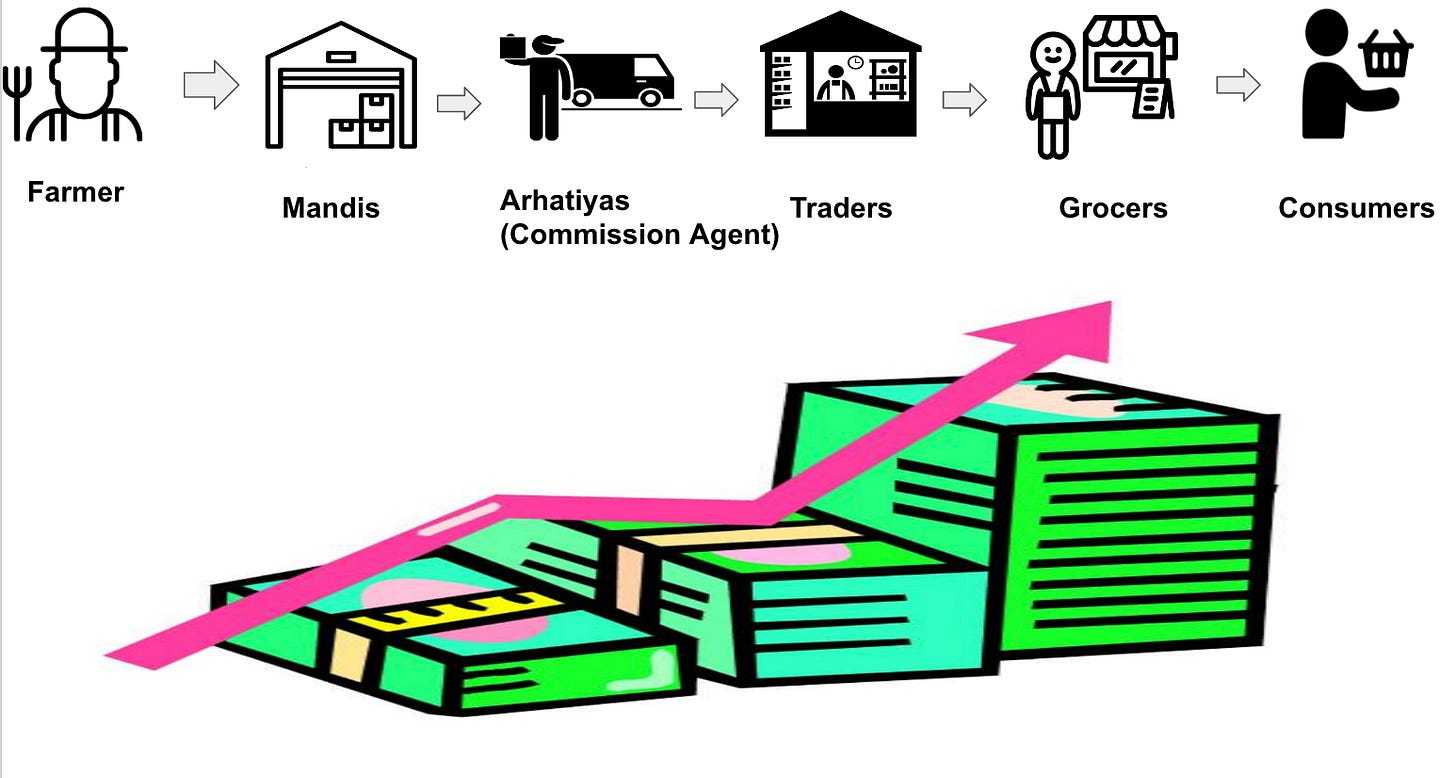

Jagadeesh makes a deceptively simple argument. He posits that the idea of ‘Farmers Share of Consumers Price’ is ‘fundamentally flawed’. As we move away from farmer to consumer, the price gets compounded on the previous person's (in the value chain) cost of goods + cost of service + cost of post-harvest losses.

Unless one wants to ignore the power of compounding, it doesn’t make sense to argue that the farmer’s price must be a function of the consumer’s price.

Jagadeesh’s argument challenges a vast array of measurement systems that have been built based on this premise: Farmers must get a fair due share of the amount consumers pay for their food bills.

Take the case of the food dollar series, which attempts to answer the question: “For what do our food dollars pay?"

In the US, in 2018, the farm share was 14.6 cents of each food dollar expenditure.

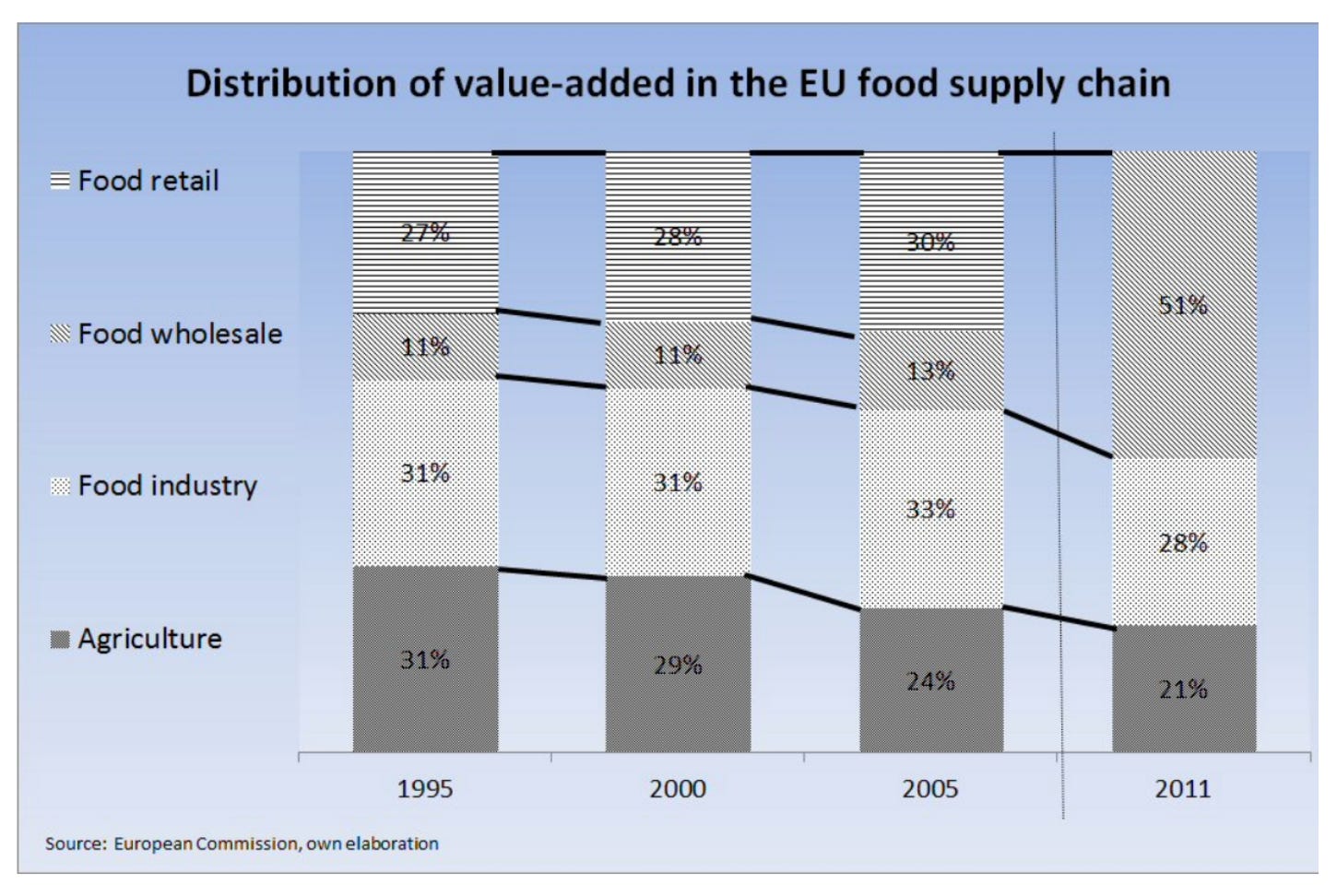

When the European Commission was asked in parliament to provide details on the average share/percentage of the final price that farmers receive for their produce, relative to the share/percentage received by other actors in the food supply chain, they found that the value-added for agriculture in the food chain dropped from 31% in 1995 to 21% in 2011, mainly in favor of other food chain actors.

If you contrast this number with 28% for the food industry and 51% for food retail and food services, it is evident that the highest value addition occurred in the supply chain far away from the farmer.

I am leaving aside the methodological concerns for now - that charts such as these reveal more the evolution of the value chain than the bargaining power of farmers. I am keener to examine the argument surrounding farmers’ share of consumers’ price, agnostic of the complexity of the methodology in place to measure the same.

Voices clamouring for farmers’ share of consumers’ prices is an extremely potent political voice, and you can hear such voices in political statements such as these:

“At the same time, we are demanding that farmers invest in more sustainable food production systems sensitive to concerns about the environment and use of scarce national resources. These demands cannot be met by relentless pressure on producer prices and their margins. The powerful in the food chain are imposing conditions on the powerless in an unfair manner, leading to reduced margins, impossible specifications demand and poor returns for investment outlay.” - Fine Gael MEP Ms McGuinness

Now let me place this data alongside the Agfunder report which stated that out of $19.8Bn venture capital that was raised in agriculture and food tech in 2019, only $7.5 Bn came from startups involved in the Upstream Journey (the boring but complex part of the value chain where the rubber really hits the farming ground); $12 Bn came from startups involved in the downstream journey (the sexy looking, but overserved parts of the agriculture value chain)

I examined this data’s relevance in my commentary on Traceability systems for subscribers of this newsletter. Net net, these data points point out an inevitable fact: Farmers’ wallet share and Investors’ wallet share on farmers’ context has been low (although the latter has been increasing if you go by previous year’s data from AgFunder) in relation to the consumers’ prices and the venture capital agritech investors are investing on consumers’ context in downstream journeys.

Central to Jagadeesh’s argument is the critical assumption that any attempt to disintermediate the agricultural supply chain is a fool’s errand. He believes that the value chain will always have some or the other intermediaries, digital or not.

If one were to unpack this argument in greater depth, one has to go back to Colin Clark, the Australian economist who made agriculture the “primary” industry and co-invented modern national income accounts. Today, we use terms like “primary”, “secondary”, “tertiary” industries sectors loosely, as a near-objective classification to talk about economic sectors. Rarely do we take time to reflect on how these classifications came to be.

For Colin Clark, development is a predestined historical arc, moving from agriculture to industry to services. He called the first, primary, the second, secondary, and the third, tertiary. Such is the impact of his theories that even though we may not be familiar with the “three-sector model”, we use these defaults, by default, in our mental models about economic structures.

Even a cursory look at the underpinnings of this model would reveal how problematic such evolutionary curves are. Take the case of hospitality. Do you call it tertiary or secondary? Or agri-input e-commerce. Do you call it tertiary or primary? Today, with the advent of technology, we are not just changing the dynamics of these value chains. We are reconfiguring the very structure of the value chains: Every Company is Becoming a Software C̶o̶m̶p̶a̶n̶y̶

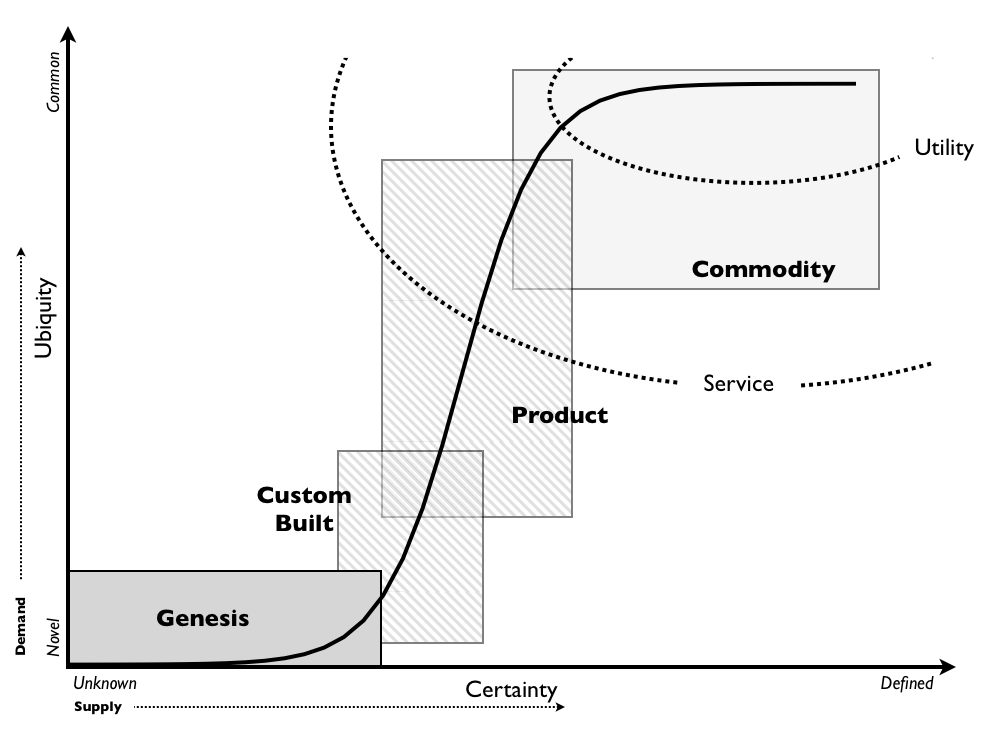

My go-to-model for understanding the evolution of a value chain ( at a meta-level) is Simon Wardley’s evolutionary graph which tracks how every system moves from genesis to custom built to product to commodity and again goes back to genesis (through a process called componentization)

Currently, we are reconfiguring food systems completely and as a result, we will build prosumer engagement models (any Alvin Toffler aficionados out here?) in which, thanks to technology, we will treat farmers as consumers and consumers as farmers.

The real question is a matter of understanding where will the bulk of profits reside in the next curve of evolution in the food systems.

We will explore this question in greater depth. For now, I will leave you with this fantastic episode on breaking down the food ecosystem which delves into this in its glorious complexity. I will cover it in upcoming Sprouting Reads.

Enjoy your weekend.

Cheers!

Venky