The Reports of Food Security Fears Are Greatly Exaggerated

Would Climate change trigger food security fears? The answer is much more counter-intuitive than you think.

<Advertisement>

After the success of four Agri-founders' retreats in West - Nashik(Jan 2024), South -Bangalore (May 2024), North-Jaipur (Aug 2024) and East - Chilika Lake (April'25), we are now hosting the fifth Agripreneurs retreat for Agripreneurs on July 11-12-13 in Coimbatore. More details here.

</Advertisement>

The Reports of Food Security Fears Are Greatly Exaggerated

The other day an acquaintance shared his anxiety about food shortages and how Climate Change could further accelerate them. He had heard about the recent rice price crisis in Japan and the food security emergency in Philippines. Are we entering a new wave of food shortages? Would this be the new normal?

If I want to instill mindless nihilistic fear about the future and sing hosanas of climate doomerism, my answer could be an emphatic YES. If I want to instill ecumenical faith about the magical wellsprings of techno-optimism that ensures the party will continue despite living in a finite planet, my answer would be an emphatic NO.

If I were to be honest with you, my answer would YES and NO.

Before I delve into the YES and NO parts, I must admit that my climate posture has been undergoing a quiet shift over the past few months, with conscious double-clicks on nuance rather than mindless doomsday prognostication and unconscious perpetual progress.

Let’s start with some fundamental facts.

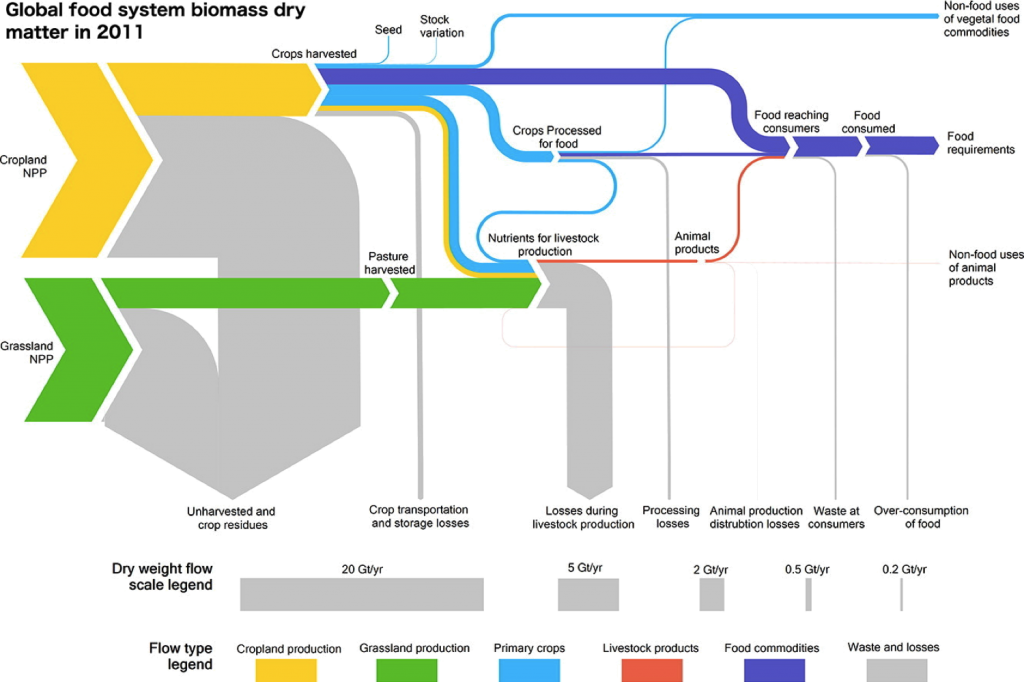

In ‘How to Feed the World’, Vaclav Smil points out that the global food production now averages about 3000 kcal per person while daily global food waste is about 1000 kcal per person. Vaclav asks a powerful question in the light of this fact: Why are we content losing one third of our income?

But, before you go further on this train of thought, let me warn you of a potential danger that lurks six inches below.

Everyone working in the food and agriculture systems think Food Waste is a massive problem worth solving.

But here is the thing.

If you think about it deeply from system lens, you would discover that this is a problem not worth solving. Yes, you heard me right. Not worth solving.

Solving for Food Waste reminds me of the scientist Masanobu Fukuoka talks about in his classic tome, One Straw Revolution:

"It is the same with the scientist. He pores over books night and day, straining his eyes and become nearsighted, and if you wonder what on earth he has been working on all that time - it is to become the inventor of eyeglasses to correct nearsightedness.”

Why do you want to be this scientist solving for food waste ?

Why do you want to solve Food Waste if there is a better way to tackle how we produce food in the first place? Granted. Food Waste sounds sexy and important in the climate scheme of things. Don’t get me wrong. Some of you might have raised millions attempting to solve this problem. But if you are really serious about solving Food Waste, you wouldn’t be solving it where the problem manifests itself. You would be solving it where the problem originates so that you can be done with it once and for all.

Sure, you could argue that food and agriculture systems are trapped in a web of incentives that will continue to feed the entropic energies that keeps the tentacles of this problem alive while purportedly investing on the other side of the value chain, in earnest attempts to solve the problem. And that's the wicked problem we have to model and a figure a way out, if we are serious about solving this problem once and for all.

And so if you are consciously wondering whether we need to be anxious about food shortages, let me assuage your anxiety with a simple question that you can validate it for yourself: If Climate Change is likely to cause food shortages, why do we give subsidies to make food cheaper and ensure that farmers continue farming?

Until that day comes when countries use policy tools to make food dearer, we don’t need to be a cassandra when it comes to food shortages. But does that mean everything is hunky and dory? Not quite.

As of June 1, India’s food grain stocks looks good enough —60 million metric tons (MMT) of rice and 37 MMT of wheat - until you look at China’s reserve stocks -about 126 MMT of rice and 105 MMT of wheat.Historically, whether it is Irish Potato famine (1845-1852) or Bengal famine (1943), the problem didn’t lie in crop failures. Both Bengal and Ireland were exporting rice and potatoes during the crisis. Both suffered from colonial regimes that couldn’t care less about the real price of hunger and took callous decisions with gross bureaucratic mismanagement fully knowing the stakes at hand.

“What happened after the famine is revealing. Between 1849-1854, landlords evicted ~50,000 Irish families and transformed their plots into productive cattle farms. This rapid conversion proves the land could support diverse agriculture under different institutional arrangements. The Land Acts (1881, 1903) provide the conclusive evidence. By facilitating tenant ownership, these reforms transferred ~9M acres to former tenants by 1914, fundamentally restructuring Irish agriculture without any significant technological change.

The lesson is clear. Ecological resilience requires appropriate institutional frameworks, not just technological capacity. Ireland's catastrophe stemmed from designed vulnerability, not agricultural limitation - Sam Knowlton

And this pattern more or less continues today with mismanagement and corruption significantly contributing to Japan’s Rice Price crisis (further buttressed by Gintan system, acreage control system) and Philippines’ Food Security Emergency respectively.

“Decades of falling per capita consumption, farmers aging rapidly, no new growers added, planted area dropping, and most importantly the government stored stock in the form of brown rice - while people consume white rice. Processing takes time and free capacity of units, which doesn’t happen instantly just because the government wants it. There is a lead time for delivery. So even though they have ‘buffer stocks’ they can’t intervene in the market effectively immediately.” - During a conversation with an Agripreneur friend on Japan’s Rice Price crisis.

And so the question we ought to think about is this.

How do we accurately model the impact of Climate Change on food systems in our head? Among the sea of papers that float around this topic, a recent paper gave me an aha moment of insight.

It provided many clues that corroborate with the evidences I’ve come across in my independent study of this problem.

The landmark study published in Nature by Hultgren et al. (2025) represents the first global empirical analysis to systematically quantify real-world farmer adaptations to climate change and project their effectiveness in mitigating agricultural losses. The research delivers sobering findings: even accounting for adaptation measures, global food production will decline by 4.4% per degree Celsius of warming, equivalent to 120 kilocalories per person per day. This challenges previous analyses that suggested adaptation could largely offset climate damages to agriculture.Unlike other studies which assume that farmers would go for the most ideal rational adaptation responses suggested by experts (duhh!!!), the paper measures three components simultaneously: 1) Crop production responses to climate change, 2) The degree of farmer adaptation 3) The effectiveness of those adaptations.

What endeared me to this paper is stronger evidence that aligns neatly with one of the core systems thinking principles that I’ve covered extensively in Agribusiness Matters system thinking canon.

Faustian Bargain of One-Dimensional Success: Agriculture is a fascinating multi-dimensional, multi-agent domain that penalizes you for one-dimensional success and you end up being trapped in a perverse game of incentives.

The paper gives strong evidence for Faustian Bargain of One-dimensional success manifesting in the form of Breadbasket Paradox.

What is Breadbasket Paradox? Modern day bread baskets - wealthy regions with moderate climates and limited heat adaptation experience—will experience disproportionate losses.

The U.S. Corn Belt, Eastern China, Central Asia, Southern Africa, and the Middle East show projected maize yield losses of approximately 40%. For soybeans, U.S. yields could decline by 50%

Typically, when we talk about Climate Change’s impact on food systems, we tend to think that the the countries that experience material poverty would be far more affected than the rich. But if you look closely what’s happening now and what will happen, you will discover quite the opposite.

With the exception of Africa which will suffer significantly, thanks to its excessive dependence on Cassava (as documented in the paper) and gross institutional mismanagement driven by colonial hangover regimes.

Climate Change is going to exact a heavier toll on the countries that look successful in today’s lens. Those who have benefited from one-dimensional yield success metrics in the current broken design of the food systems will pay a heavy price, thanks to climate change.

“We estimate average losses of 28% in the lowest-income decile but more moderated losses of roughly 18% across deciles 2–8. In the highest-income deciles, average losses increase to 29% (ninth) and 41% (top). This result is partially because lower-income populations tend to live in hotter climates, in which present adaptation rates are higher, and in the tropics, in which high average precipitation reduces warming impacts” - From the Nature Paper we have been discussing so far.

To understand why this is the case, we have to understand the contradictions that are driving the existing food systems towards weakness. There is a fancy word that I learned many years ago and has been living rent free in my head: Catabolic collapse.

Catabolic collapse of food systems

Real world is not what we dream in Hollywood. Food systems aren’t going to collapse one day leading to widespread panic and shortages. The impact is going to be protracted but steady erosion of food system resilience.

What is catabolic collapse?

The word ‘catabolism’ comes from the biological processes of metabolism. Anabolism is how larger, complex molecules are formed, requiring energy input and catabolism is how complex molecules are broken down, releasing energy.

When does complex food systems break down and start cannibalizing its own components? Take the case of rising temperatures and let us run through a worst case scenario