Three things They Don’t Tell You About Digitising Food Quality

Plus! My idiosyncratic mapping of the Indian agritech players (Intello Labs, Agnext, Zentron Labs) involved in digitising food quality.

Dear Readers,

Hi! My name is Venky. I write Agribusiness Matters every week to help us make sense of vexing questions of food, agribusiness, and digital transformation in an era of Climate change. Feel free to dig around the archives if you are new here.

This essay owes a lot to many enlightening conversations with VS Vivek (CEO, Subjiimandi.app), Anurag Duddu, (CEO, Farmrevv), Sivam Krish (CEO, GoMicro), Vikas Birhma (CEO, Gramhal), and many farmers with whom I’ve had the pleasure of interacting during my travels.

If you stir a big pot with all the problems that are plaguing Indian Agrculture and let the pot simmer for a while, it will be obvious to you eventually that quality is the deep rooted sediment layer - the filtrate of most problems that make up the agrarian crisis we see in our midst.

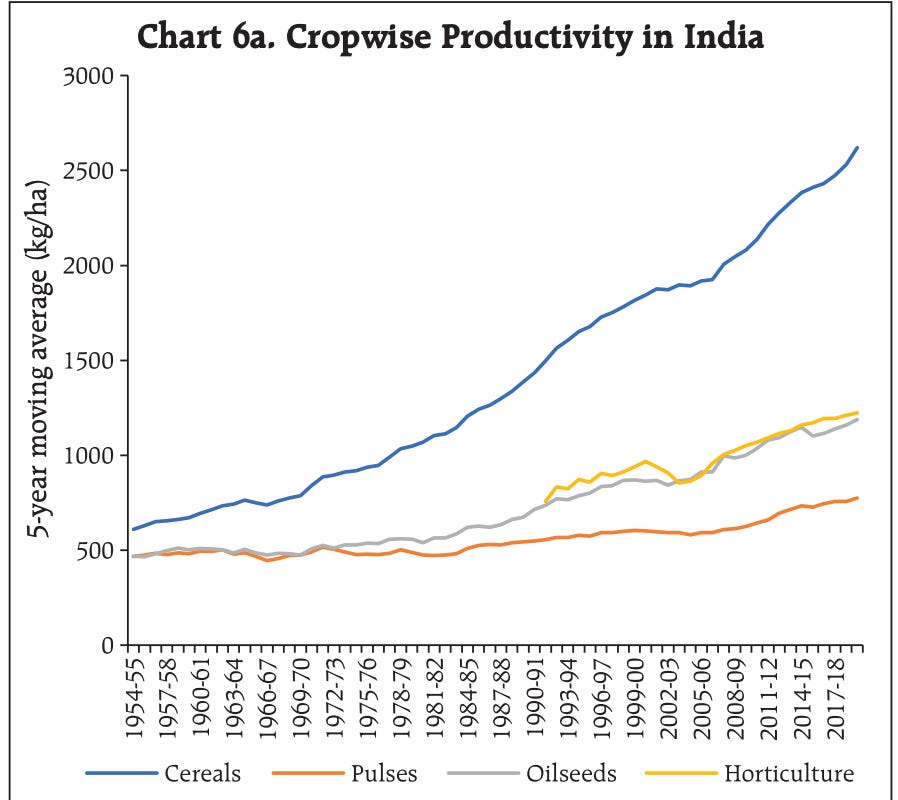

01/ Why do Indian farmers continue to grow cereals, chasing assured incomes, despite obvious “policy level” evidence that those diversifying into horticulture are earning much more?

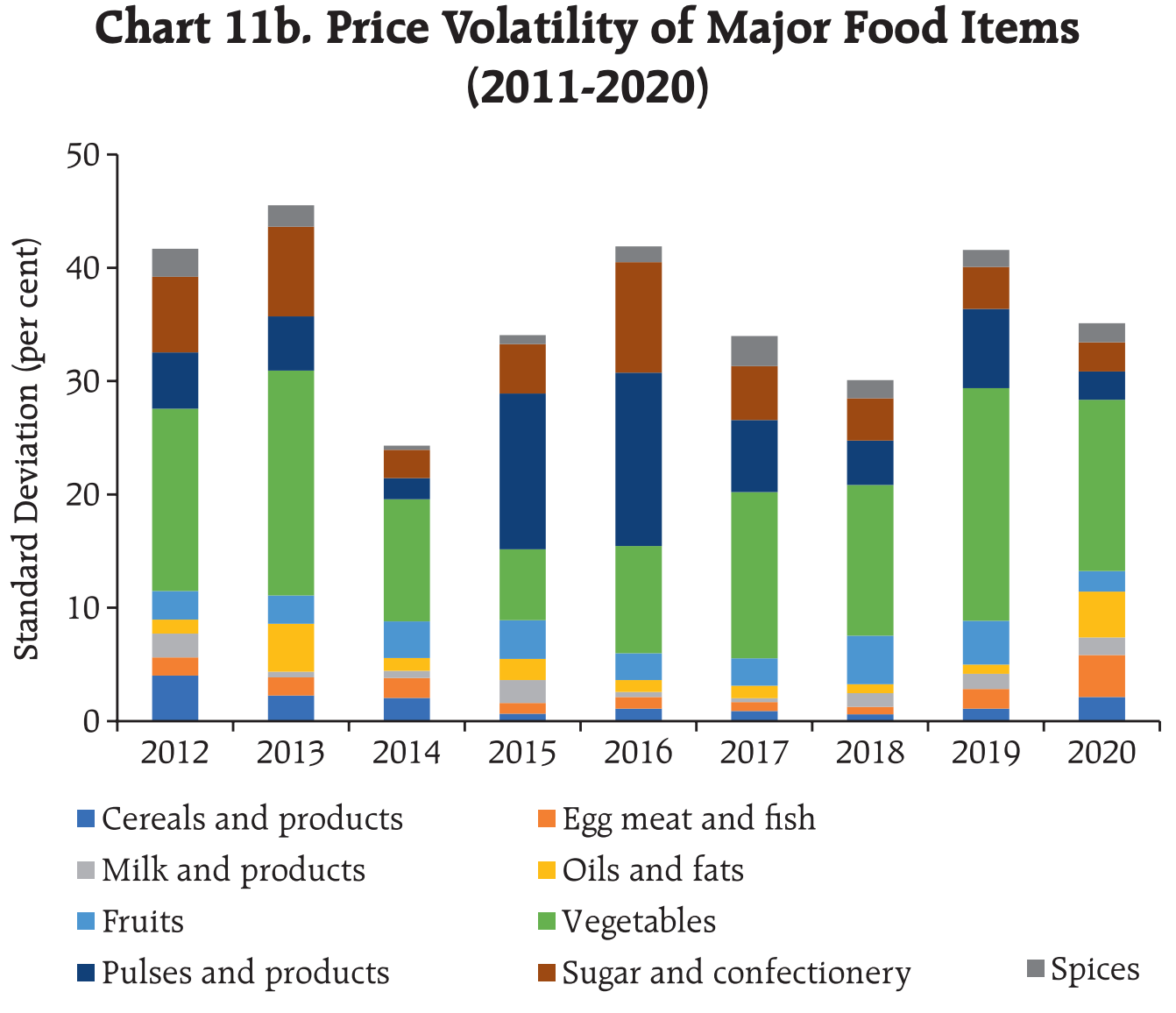

02/ Indian farmers may not be interested in writing opeds about lesser price volatility for cereals, when compared to fruits and vegetables. But their cropping behaviours clearly reflect their nuanced understanding about ground realities.

**Thing 01**

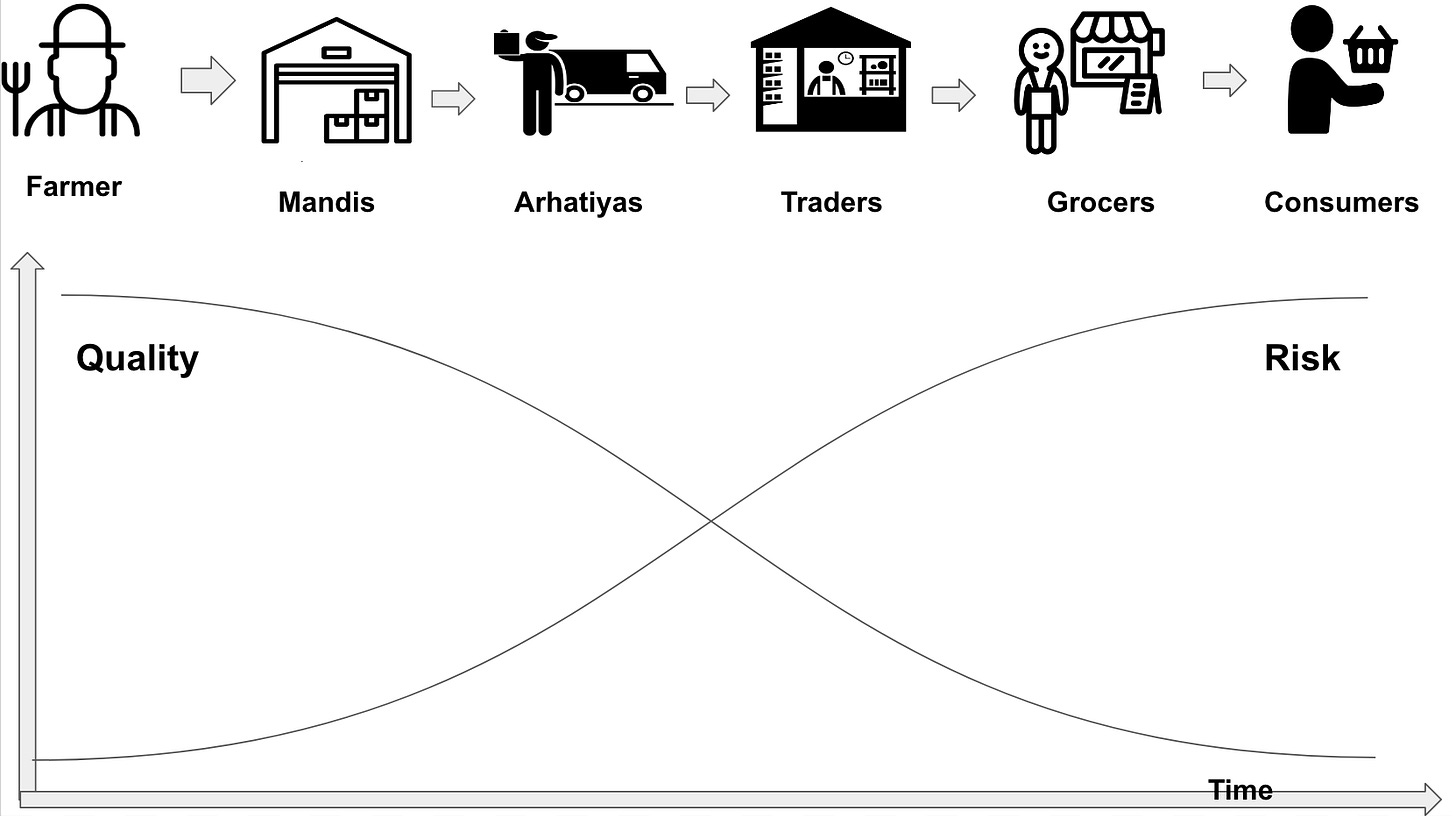

In theory, “Grow Quality Food = Earn Money” may sound appealing to agritech startups and investors betting on the future. In practice, those who grow F&V, alongside buyers and traders who take them to the market, understand the price volatilty at stake, where the brutality of “Time= Money” is painstakingly obvious.

03/ If you look at the data, the glass is half full: “Horticulture production has outpaced food grain productions since 2012-13 and currently accounts for around 35 per cent of total value of crop output in the agriculture sector.”.

04/ And so the nagging question remains: What is the current bottleneck that is coming in the way of faciltating this behavioural change among Indian farmers to move past “India’s obsession with food grains”, as one pro-market bias economist had once put it?

If you browse through most opeds that analyze the agrarian crisis and the interrelated problems in supply chain in a developing countries context, in response to such problems, most of them talk about the need to increase the capacity of warehouses or the capacity of cold storages.

However, when you peruse the data, what you see is something else.