What If We Believed In Indian Agtech to solve the Agrarian Crisis?

What would happen if we were to believe in the original promise of Indian Agtech?

We’ve had several new subscribers join us here this week.

Orientation: My name is Venky. I write Agribusiness Matters every week to have straight talk on Digital Agriculture, Agritech and Agribusiness Matters. Because let's face it. Agribusiness matters. You probably signed up from here.

I am sorry for the last-minute announcement. I am doing a LinkedIn Live Event today, August 26th, 12 PM IST on this topic: What If We Believed in Indian Agtech to solve the Agrarian Crisis?

You can RSVP for the event here. The event will be broadcast LIVE on LinkedIn and Youtube. I am excited to kickstart this conversation with one of my earliest mentors in the domain of Indian Agriculture: Jagadeesh Sunkad.

Ever since I began working in Agritech, I have been having deep and beautiful private conversations on various fundamental aspects of Indian Agriculture with Jagadeesh. And I am excited to open up this dialogue with a broader audience.

If you noticed, the title carries as much wickedness as the domain of agriculture itself. And I would be remiss if I didn’t explain why I chose this title.

Allow me to set the context for today’s conversation. I think it’s important to spell this out, in context with where Indian Agtech is, where it was, and where it could be. This story is also deeply personal to me as it mirrors how my relationship with Agtech has evolved over the years.

Shall we get started? This is going to be a long piece. So, I suggest you pick up your green tea and settle down to read.

If you are familiar with Bollywood movies of the seventies and eighties, you couldn’t have missed out the time-tested story formula of lost-and-found brothers of the same family separated at the beginning only to be reunited at the end.

You remember these stories right?

Two brothers, born from the same womb; one lands up in a rich family, the other grows up poor, struggling to make ends meet; the rich sibling eventually gets into a power conflict with the poor, and during the climax, the mother intervenes and tells the truth to save their lives. The brothers are united and finally, all is well in the universe.

There was a touch of innocence in those stories of yesteryears, something which I miss terribly these days.

If I were to dramatize the story of Indian Agriculture and Indian Agtech, I feel tempted to tell one such story of two siblings who were born from the same womb, but in different eras of this vast subcontinent. The elder one discovered his youthful exuberance in Socialist Bharat. While the younger one was born in a globalized India with access to unlimited capital and exponential technologies.

The elder sibling, the good old Agriculture fellow, is now jaded and cynical to the core, having already seen three waves of agricultural innovation-

1) The Age of Mechanisation starting from the 1700s, when horse-drawn seed drill was invented by Jethro Tull. This birthed the cotton gin, combined harvester-thresher, and gasoline-powered tractor.

2) The age of Ag Chemistry, starting from the 1940s, when chemicals that were used for the war were repurposed for input-intensive agriculture

3)The age of Precision Agriculture, starting from the eighties, when the question of how to produce more with fewer inputs began to be entertained seriously. This age also birthed the biotechnological age, starting with crop breeding for traits and varieties with high yield potential, and identifying the right complementary inputs to expand the agronomic potential and bridge the gap between yield potential and agronomic potential.

As the elder looks at his sibling amidst the rise of the fourth wave of agricultural innovation, starting from the 2010s, the VC-sponsored age of UAVs, data-driven agriculture, he harbours doubt and derision, for he is still struggling with existential issues, not being able to escape from the old pieties of scarcity and food security, trapped inside cascading effects that were unleashed by a series of socialist government policies to cope up with the food crises of the sixties.

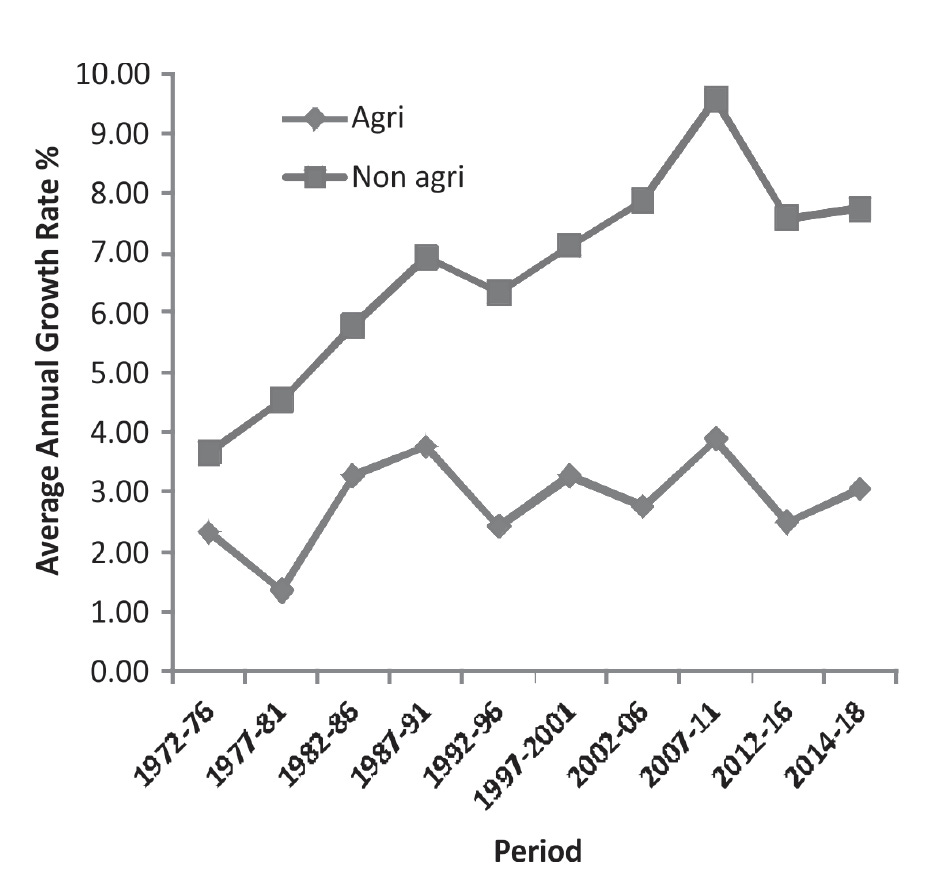

If you see the data, you would realize that this scepticism isn’t unwarranted.

Ever since the rise of the third agricultural innovation, coinciding with the bold economic reforms of the nineties in which Socialist Bharat shed its skin, thanks to the forces of Liberalization, Privatization and Globalization, the gap between the agricultural sector and non-agricultural sector further worsened. While the non-agricultural sector climbed northward on a growth path, the agricultural sector stagnated with an average growth rate of 3%

Today, as the elder looks at the younger, they are unable to relate with each other. They both talk different languages. The former either speaks Hindi or a variety of regional languages, while the latter glibly talks in fluent English.

The younger one talks about precision agriculture, flying drones and gushes excitedly about software feeding the world, while the elder one talks about subsidies, MSP price regime, unable to exercise autonomy to decide between keeping grains in the warehouse and keeping money in the pocket.

While the younger one celebrates the recent ordinances as a watershed 1991 moment in Indian Agriculture, the elder one shrugs off the enthusiasm, dismissing the new-age Agtech entrepreneurs as new-age techno middlemen who have ventured out to reduce margins and increase their profits at the expense of farmers.

While the younger one spells out a perfectly scripted, PR-approved narrative about dedicating the work they do in technology in the altar of transforming farmers’ lives, the elder one looks at the younger one with scorn, smirking out loud,

“Look at these technophiles who have the audacity to think that agriculture is simply an optimization problem.”

In 2017, when I got bored making fancy presentations, I decided to quit my seven-year consulting life. I wanted to get my hands dirty, both literally and metaphorically. I was driven by my “baptism of fire” purpose: What does it take to transform Indian farmers’ lives?

Sooner, as I started immersing in Agtech, I realized the cringe-worthiness of this purpose-driven mission statement. Even though I was damn serious about my purpose, I couldn’t reconcile what I was apparently doing - building Agtech software products - with my purpose.

I must confess this.

I once had a LinkedIn profile that looked like this. Here is the saddest part: A good friend of mine, who wrote a book on Personal Branding, featured my profile as a case-study and thus my naivete got etched in posterity.

Let me make myself very clear where this cringe-worthiness was coming from.

It wasn’t coming from suspecting the intentions of Agtech founders, who often talked about helping farmers win and doubling their incomes, dancing to the tunes of what the investors and the larger audience wanted to hear in the first place.

As I started travelling to the fields, meeting bania agri-input traders in rural markets, Ag Executives of large Agri-Input firms, studying various dimensions of the agrarian crisis, as my understanding of Indian Agriculture deepened, I could clearly sense that it took more than building a piece of software to address the gravity of the agrarian crisis.

A week ago, Shubhang Shankar wrote a fantastic retrospective piece on the 2010 Agtech scene, providing a much-needed ground-truthing (pun intended) to reflect on the promises Agtech once held and what really turned out in the end. Despite his optimism about the future, his verdict was clear: The King is naked, despite what he professes.

It resonated with my conclusions that I had independently arrived elsewhere while studying some of the leading Indian Agritech startups like Agrostar.

In the words of Shubhang Shankar, How did the “insurgents end up replicating the incumbents”?'

As he further writes,

Say it out softly – there is no disruption in AgTech. Ambitions have mellowed. Valuations will follow. AgTech in the 2010s was essentially off balance sheet R&D for Big Ag and now the prodigal son wants to return home. AgTech isn’t displacing the incumbent industry, it is replicating it.

When I decided to quit the agritech startup I was working for and become an independent Agtech consultant last year, it was primarily motivated by this understanding.

If I was serious about what I set out to do, building yet another Agtech startup doesn’t simply cut the mustard.

If one were really serious about addressing the gravity of the agrarian crisis, one has to address the problem at different levels.

From the level of policies and incentives that dictates the production patterns of Indian farmers.

From the level of productivity, which get subsequently shaped by the policies and incentives that are offered by the government. Agriculture economist Bruno Dorin has shown that rice, wheat, sugar absorbs more than 60% of public grants. In such a scenario, given the input subsidies the farmer gets for water and fertilizers, as Bruno Dorin eloquently puts it, productivity is reduced to a simple mathematical function: ‘Productivity = Irrigation + Fertilizers’.

From the level of creating national agricultural markets, which goes far beyond plugging into e-NAM via a piece of software.

From the level of understanding that unless farmers discover their autonomy to set their own prices for their produce, agricultural markets will fail to empower them.

And from the level of understanding at a deeper level that it is reductive to equate rural with agriculture alone. Agriculture is one part of the rural economy, albeit vital to create the required multiplier effect in the rural economy.

From the level of understanding that digital agricultural echnologies can empower farmers, only when the agri-input supply chain is transformed.

And to address the agrarian crisis in all these levels, Indian Agriculture needs to talk with Indian Agtech.

Despite their differences in world-view, both need to talk. The elder needs to have an open mind to entertain the experiments that are being done by the younger ones, and the younger one needs to listen to the wisdom gleaned by the elder one from the previous agricultural innovations.

Through these dialogues ( I will be doing it hopefully on an ongoing basis), I am trying to bridge the chasm between Indian Agriculture and Indian Agtech.

Beyond two different world-views, two different ontologies, is it possible to have a dialogue?

Only when Indian Agriculture dialogues with Indian Agtech, there is a glimmer of hope for us, facing a climate crisis and the possibility of hunger in an age of pandemic, and for farmers, who have suffered the economic brunt of policies that favoured us, the consumers over the farmers.

Good morning 🌞🌞🌞