Will the Real Agritech Platform Please Stand Up?

If actions really speak louder than words, now would be a good time to take a hard look at how we define agtech.

Many moons ago, the legendary investor Paul Graham fired off a tweet which set off tea-cup outrage among entrepreneurs dreaming of platforms and marketplaces.

The problem is as old as the hills.

We are wont to define what we do based on word currency stocks which trade high in the hype cycle of emerging technologies.

Naturally, everyone who uses technology in agriculture love to call themselves an agritech startup which, in a feverish world dreamt by technophiles, could very well be “the last resort for farmers to keep their farm cycles running and their lands sustainable”.

I promise. I am not making this up.

I found these and more dramatic words of phantasmagoric wisdom in Inc42+’s seventh playbook titled, Farming 3.0: India’s Mission Agritech.

When I first stumbled upon this playbook, I perked up reading the following lines,

“Many startups such as Aibono, CropIn, and AgroStar took the leap of faith early on, even though the sector was not considered profitable. And they proved that agritech could help solve crucial issues such as wastage, land utilisation, market linkage and credit availability while turning a profit. These startups, along with others, not only built economically viable models using tech and data but also scaled across geographies in a short period.”

My apprehension over the playbook’s hoity-toity title, which sounded like a love child of a Gartner Report and the script of an upcoming Akshay Kumar movie, rang true.

(For non-Indian readers, Akshay Kumar is a popular Bollywood actor who loves to make formulaic “social message” movies that tell powerful stories of social change happening in India.).

Dear Bollywood script-writers,

If you ever find yourself out of ideas, go ahead and read this playbook. In fifteen minutes, I can bet you will be all set to write a mass-appealing agricultural “social message” entertainer movie script for Akshay Kumar.

In fact, I will go a step further. Allow me to spoonfeed you.

Here is the rough treatment of the script, using golden insights from the playbook.

Akshay Kumar is fired from his IT job during Corona times. He decides to go back to his native village to pursue his dream occupation of farming, which also happens to be the “resilient sector” during the times of the pandemic. As he fumbles and bumbles his way through, he finds himself ridiculed and bullied by his evil “sahukar” (middle man) father-in-law who dismisses this urban bloke out of touch with the ground realities of farming.

During the interval time block, Akshay Kumar meets smallholder farmers and wakes up to the painful realities of farming.

Seeing “farm incomes depleted at the hands of several middlemen in the food supply chain”, Akshay Kumar decides to start an agritech startup, and over the course of a rah-rah rousing song towards the climax, he changes the face of Indian Agriculture through the magical intervention of tech and data.

If anyone reading this is feeling excited to pitch this storyline to Akshay Kumar or any other Bollywood producer, do consider hiring me as a script consultant. I have more ideas:)

Jokes apart.

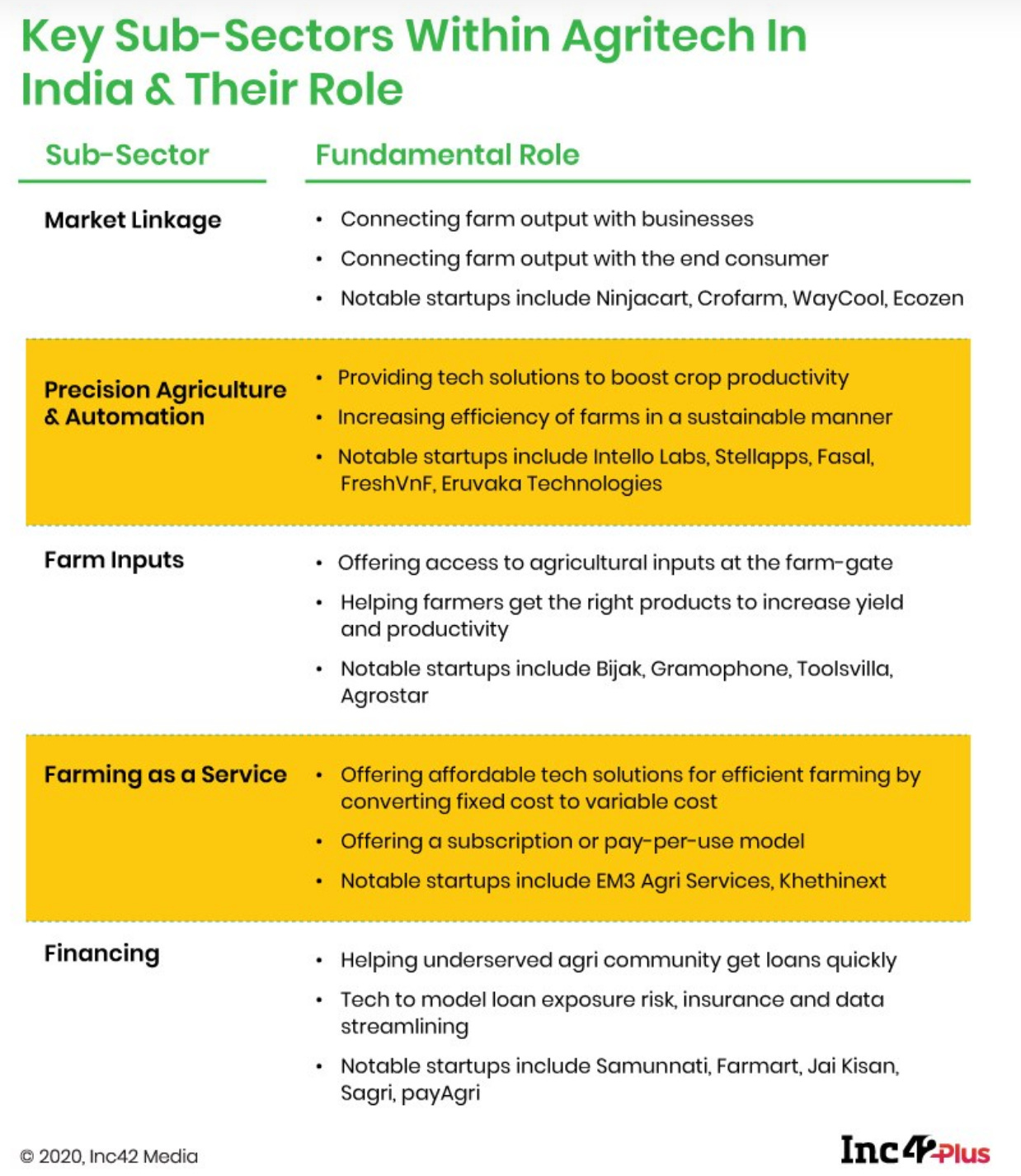

Here is *their* depiction of Indian Agritech Landscape, which serves as an excellent showreel for movers and shakers investing in agritech and their darling startups.

To be honest, I have no qualms about subjective depictions of agritech landscape, which perpetuate cliched trickle-down economics myths from developed countries to developing countries.

To each their own, really!

I have also gotten used to the naivete often seen in such mainstream startup media in painting middlemen, who provide hyper-local ‘expertise in credit, storage, transportation, quality assessment, and counter-party risk reduction’, as “evil”.

What really pains me is this.

Is it too much to expect a playbook, which purportedly tracks the evolution of agritech in India, have some iota of clarity in defining agritech in the first place?

Think about it.

If you are in the business of selling agri-inputs through free-but-biased agronomy content advice, can you really call yourself “agritech” player?

If you are in the business of transporting potatoes, onion, and tomato (POT) from farmers to food grocers in the country with an assured delivery period of 12-15 hours, can you really call yourself an “agritech” player?

The problem is further compounded by the fact those who originally started off with agronomy advice and selling agri-inputs are now looking at buying produce from farmers and creating subsequent market linkages.

And those who originally started with facilitating reverse-auction of farm produce among farmers and traders are now looking at selling agri-inputs.

In such a case, who on earth would you call a real “agritech” player? Anyone and everyone?

At the end of the day, It doesn’t help anyone to treat the word “agritech” as an umbrella term, which can include anything from financing to market linkages to farm inputs to precision agriculture and automation.

If you think deeper, perhaps, there could be a reason behind this “agritech as an umbrella-term” narrative.

If you consider the ambition that most agritech startups have to be a new kind of technology-driven middleman between consumers and farmers, it makes sense why playbooks would drive an umbrella-term narrative, in the earnest hope that agritech startups would one day grow up to replace the multifaceted services middle-men offer currently to farmers - credit, storage, transportation, quality assessment, and counter-party risk reduction- and more importantly, own the critical principal risk involved in an occupation like farming.

My bone of contention with umbrella-term narrative is this: When you obfuscate what agritech is, without a deep understanding of the domain, you perpetuate confusion and groupthink among the minds of agritech founders and investors.

Case in Point: Read this honest admission from an agritech founder who decided to return his investors’ money after struggling with an output market linkage marketplace model for 22 months.

Brief — A solution suggested most of the time is “eliminate the middleman or de-layer the supply chain”. What we learned, it is easy to de-layer the chain but not easy to de-layer the costs.”

And if you go one step further, you would realize that these playbooks perpetuate another dimension of confusion.

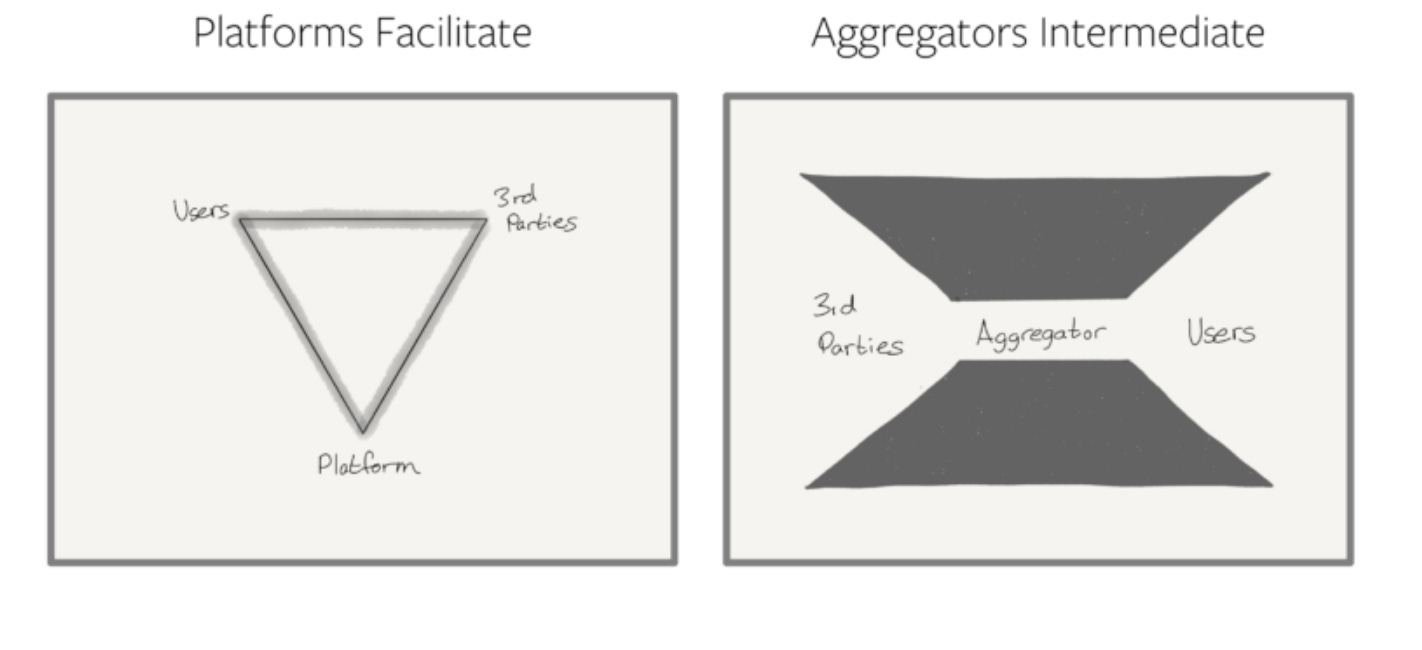

They conflate platform with aggregators. They sound similar no? And lest you think, how does it matter, remember this. Many anti-trust battles worth billions have been fought over this "academic" distinction between Platforms and Aggregators.

Here is how Ben Thompson, in his blog post, distinguishes a platform from an aggregator.

In Ben's words,

Platforms are powerful because they facilitate a relationship between 3rd-party suppliers and end users; Aggregators, on the other hand, intermediate and control it.

Let’s go back to the Agritech Landscape graphic I shared above. How many of you can discern Platform players from Aggregator players among the agritech startups in ndia?

Probably, some of you might be sneering, in response, “What use does all of this criticism serve, if you don’t offer constructive alternatives”

Fair point. I will address two questions which have been shoddily addressed IMO in the playbook.

1) How do you track the evolution of agritech landscape in a developing country like India?

2) What constitutes a fair definition of agritech, when you think from first principles?

Let me start with the first question.

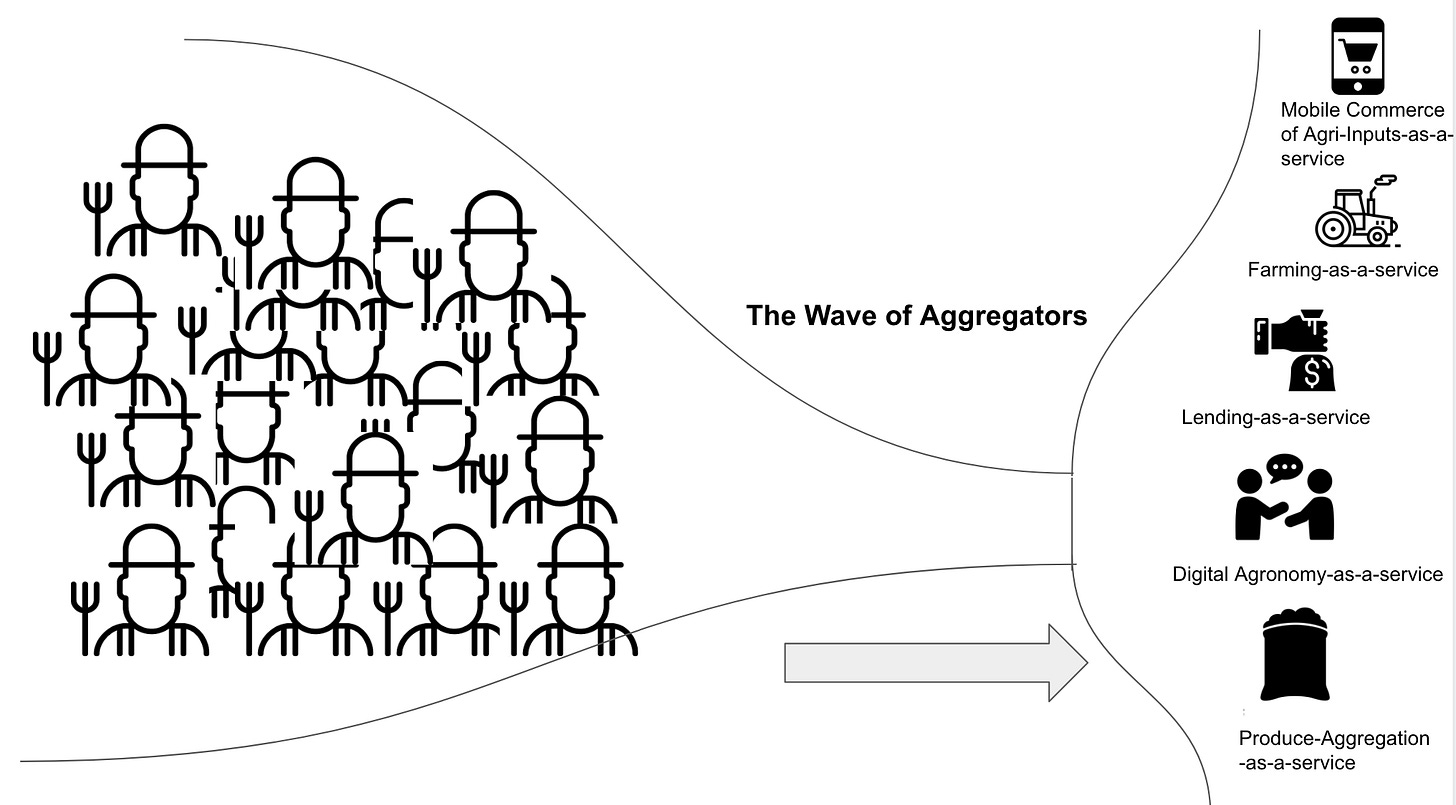

If you really cut down the chaff and focus on the essentials, you would realize that we are in the second wave of agritech.

I would characterise the first wave as the wave of aggregators, which started from somewhere around 2015 and came to a halt during April 2020, just when the shit hit the fan, marking the arrival of the pandemic.

During the first wave, whether it was selling agri-inputs through missed-call/mobile commerce or renting tractors or aggregating produce to create market linkages, at the level of business model, all of these startups are essentially aggregators.

Back in those days, Agrostar was the cynosure of eyes among aggregators.

In a Tale of Two Algorithms in Agri-Input Retail, I summarized their game play and shared my concerns about their profitability.

Agrostar is playing the Amazon Aggregator Algorithm game, with a centralized warehouse and its dedicated fulfilment network. Which means they have to manage inventory and warehouse costs, take care of distributor margins, and sales commission and so on. Their gross profit margins will go down south until they fully optimize their fulfilment network by making further investments in logistics networks.

Today, the writing on the wall is clear.

Aggregator models can never be profitable. And I am not just talking about Agrostar.

Ninjacart, WayCool, Bighaat which are built on Aggregator models can never be profitable.

Aggregator business models require deeper, ongoing investments at the last mile to serve the marginal small holder farmer and unless you are willing to bleed red, unit economics doesn’t make sense to serve them.

Farming-as-a-Service startups, which also followed aggregator models like Oxen Farm Solutions and Gold Farm , realized that they could never be profitable and decided to shut shop.

And when surviving aggregator startups came to this painful conclusion, they decided to partner with Agri-input firms.

Earlier in 2019, Bayer and Agrostar jointly announced that they would be partnering to deliver seeds and crop protection products directly to the farmer’s doorstep. Back then, I had dissected that partnership in detail.

Plantix announced their partnership with Shriram Farm Solutions. I also analyzed that partnership in detail.

More recently, Big Haat announced a similar partnership with Bayer.

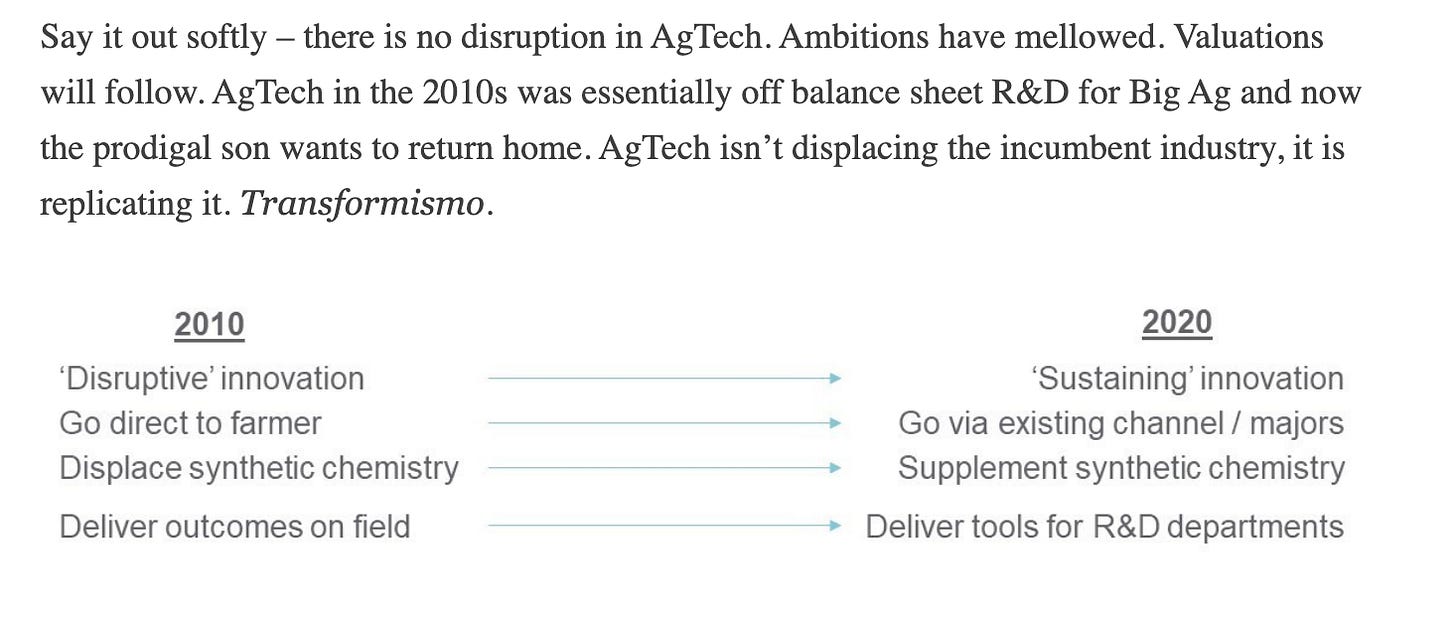

All of these partnership announcements made it clear that these agritech startups which once ambitiously aimed to serve farmers directly, now have tamed their ambitions and decided to partner with existing channels.

Shubhang Shankar, in his fascinating article on the evolution of Agtech, spelt the bigger picture in clearer terms.

The pandemic forced agritech startups stuck in Aggregator models to either evolve by partnering with agri-input firms or die.

The Second Wave of Agritech began around the launch of Vegrow around April 2020.

It also marked the ascent of Integrators like Dehaat, Gramophone coming to the fore. Agribazaar announced their foray into agri-inputs segment.

We are now officially in the second wave of agritech, the Wave of Integrators.

Aggregators Versus Integrators

As I had mentioned earlier, in my article, What the *Puranas* of Retail can Teach Us about the future of Agri-Input Retailing

"In an aggregator play, suppliers are at the risk of getting commoditised, because it is the Aggregator and not the Agri-Input manufacturers, who is building a captive relationship with the end-customers- the farmers - through customer service and fulfilling the orders at the last mile, through agri-input retailer network."

Aggregators commoditize suppliers, while integrators work on the basis of differentiation, providing personalized end-to-end services, across the agri-input and agri-output supply chain.

Aggregators seek to serve the maximum number of consumers. Integrators seek to monetize consumers to the maximum extent.The best example which demonstrates this in action is the concept of micromarkets, as defined by Gramophone. In their Co-Founder, Tauseef’s words

[Author’s Note: Tauseef is a good friend of mine]

“Since 2019, we’ve adopted a micro-market strategy similar to the OYO model. There is a common last-mile delivery network for two to three districts in a state. It helps cut costs, makes each cluster operationally profitable, and also allows us to go deeper in every geography. This model makes sense because farming patterns, weather, and soil types change every 100-odd kilometres in India.”

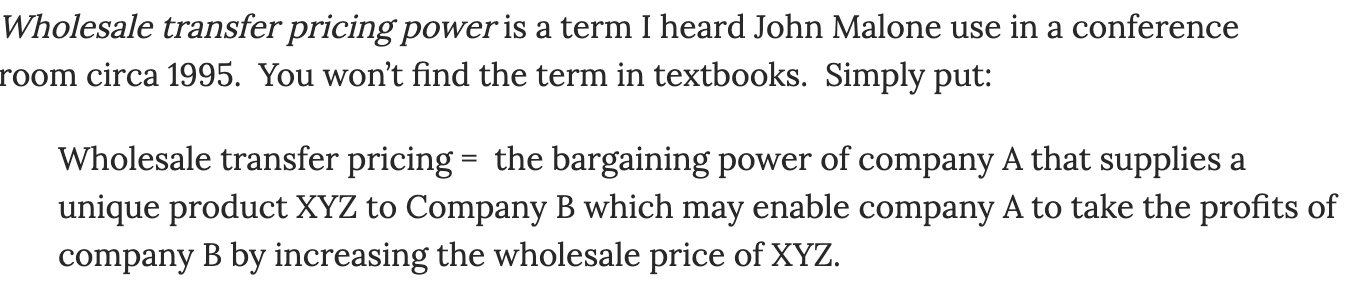

Aggregators commoditize agri-input manufacturers. Integrators disrupt the business of agri-input manufacturers.This is an extremely crucial point. Just because, integrators work on the basis of differentiation, one shouldn’t undermine the disruptive nature of their game. All integrators work to acquire whole sale transfer pricing power of agri-inputs.

In other words, by acquiring whole sale transfer pricing power, Integrators in Indian Agtech are attempting the FBN game play, which has been disrupting the industry pricing tactics and bringing more transparency to the end customer, farmers in developed countries’ markets.

Let’s now get to the second question.

2) What constitutes a fair definition of agritech, when you think from first principles?

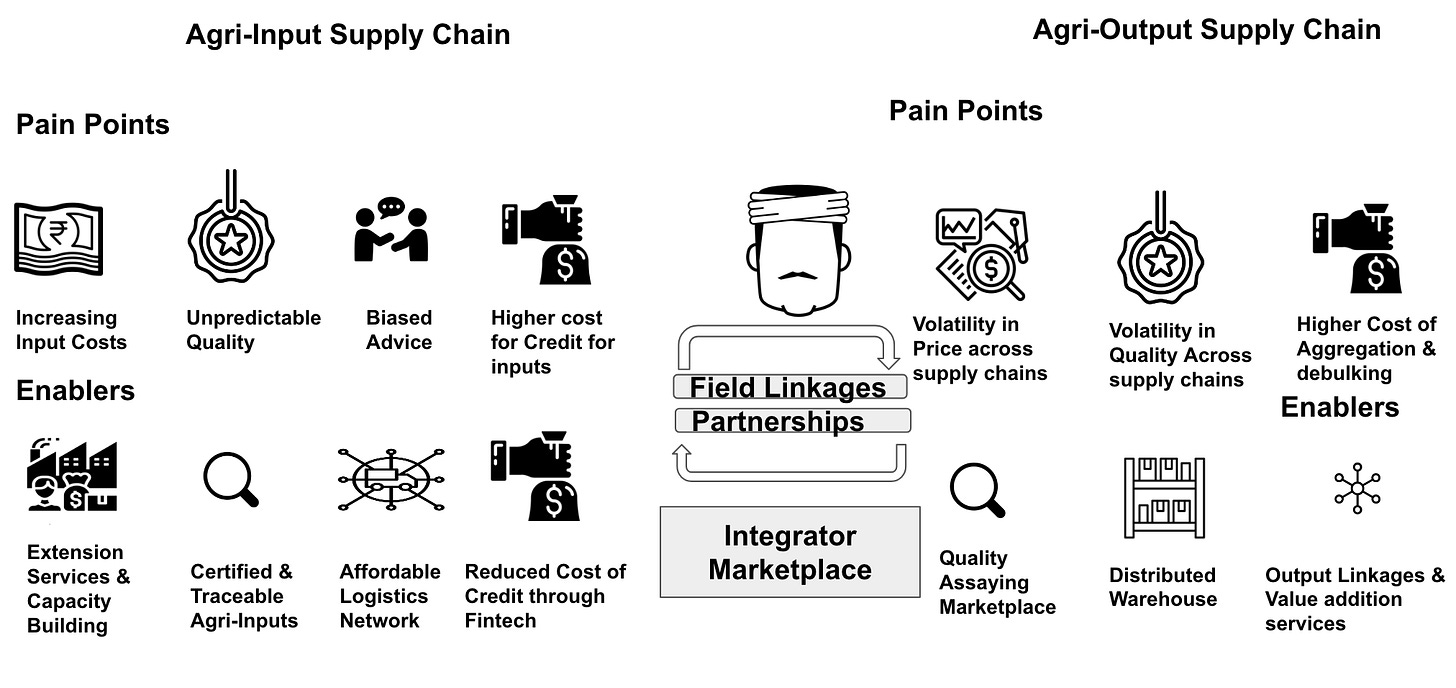

The holy grail in agritech has always been to build one collaboration platform, which brings together valuechain players from both ends, the input side on the left, and the output side on the right,

And that’s exactly what you see in Integrator Game play. The playbook, if you dig at a metagame level, looks something like this.

Integrator Gameplay will be the future of Agritech, and I will sketch out Integrator Theory of Agritech in more granular detail in the coming weeks ahead.

Stay tuned.

The important thing Jeff did was to go to investors and say "Don't ask for profits; I will only focus on growth" and he successfully did this for a long time. I don't think anybody in Indian agriculture sector has the courage to say a similar sentence. Nor would any one listen to it.

Most importantly, no startup (Indian) can deliver on such a claim; as they are yet to come to grip with the real problem.

My occurring "Indian Agritech Startup" = "We have an app/software/data, we believe we are solving a problem and someone invested in us"!