Reflections on Indus Valley Annual Report 2025

Reflections on Indus Valley Annual Report 2025

Steve Jobs once remarked, “Maybe Thomas Edison did a lot more to improve the world than Karl Marx and Neem Karoli Baba1 put together.”. I don’t know why. This line kept hovering over my subconscious as I reeled in the afterglow of reading the 188-slide Indus Valley Annual Report 2025.

This acerbic remark came after Jobs’ direct encounter with India’s abject material poverty, which shattered many illusions he (and other Californians) once nurtured about India during the trippy counterculture sixties and seventies.

Indus Valley Report 2025 does something similar, albeit, it raises far more powerful questions through the numbers that hide more than they reveal and the narrative that remains unsaid.

This must be obvious.

Following the footsteps of the legendary Mary Meeker,

and the team at Blume have created a new category of content game through their "Indus Valley Annual Report" (IVR). In its fourth year, IVR Network Effects has now ensured that every respectable VC firm worth its salt produces kickass thought leadership.For starters, check out the second edition of India Insights by India Quotient 2025 that was launched days after IVR || Ankur Capital, I am told, is launching their generalist Climate Report soon ||I find it deeply fascinating to observe the flywheel that has now kicked in with their "Content-First VC Playbook" - curating startups and their proprietary data sets that get the status of being featured (on the supply end) while providing scalable founder guidance to startups poring through their report (on the demand end)

Much like the Hindu Lord Ganesha who embodies a beautiful amalgamation of the macro (he is gana, lord of categories) and the micro (his vaahan (vehicle) is the humble mooshika mouse), the report bridges the macro -India - with the micro -Indian startup ecosystem denoted by the catchall moniker ‘Indus Valley’.

So what is the India and Indus Valley Narrative that the authors construct with data?

Section 1 - India:

Over the past five years, India’s economy saw a sharp pandemic-driven contraction, followed by a stimulus-led recovery fueled by government spending and low interest rates, which triggered a credit and consumption boom but also rising inflation and deficits. The RBI’s tightening slowed growth as consumption weakened amid stagnant wages. Structurally, India remains a consumption- and services-led economy with weak manufacturing due to land, labour, and capital challenges. Household debt is rising, savings are declining, and gold remains a key asset due to poor land collateral systems. A small affluent segment, India1, drives most consumption, investments, and market growth, deepening economic divides as the broader population lags in income and consumption.

Section 2 - Indus Valley:

The Indian venture ecosystem, or "Indus Valley," is showing signs of revival after a funding slowdown, with early-stage deals stabilizing but late-stage capital still scarce. Seed rounds are fewer but larger, driven by experienced founders, while MicroVCs are rising to fill early-stage gaps. India’s unicorn count is inflated, with only 91 of 117 truly valued over $1B, and startups are increasingly flipping back to India to list as IPO activity hits record highs—especially in the booming SME market. Venture debt is growing as equity tightens, bringing new risks.

Quick Commerce has exploded, reshaping retail with rapid growth, expanding SKUs, private labels, and ad revenue, though its long-term sustainability faces TAM limits and competition. Meanwhile, India eyes building foundational AI models, backed by talent and growing GPU access. Startups are also innovating for India2 with voice, microtransactions, and culturally tuned JTBD playbooks. Return-to-origin (RTO) challenges push new strategies in e-commerce, while diaspora marketing emerges as a focused growth lever for Indian brands globally.

For a report that embodies the Ganesha, it strangely leaves the Elephant in the room: Agriculture and Agritech’s glaring absence has been a major disappointment for me in the entire Indus Valley Report series.

To be fair to the Blume Team, in this ‘generalist’ report, "rural" appears five times while “Agriculture” appears thrice in the context of GDP share by sectoral split, % Share of Gross Value Added (GVA) Agriculture and disguised unemployment in agriculture. Agritech makes a unintended solo appearance (through Bharat Agri) while talking about how startups are addressing “Return to Origin” in e-commerce.

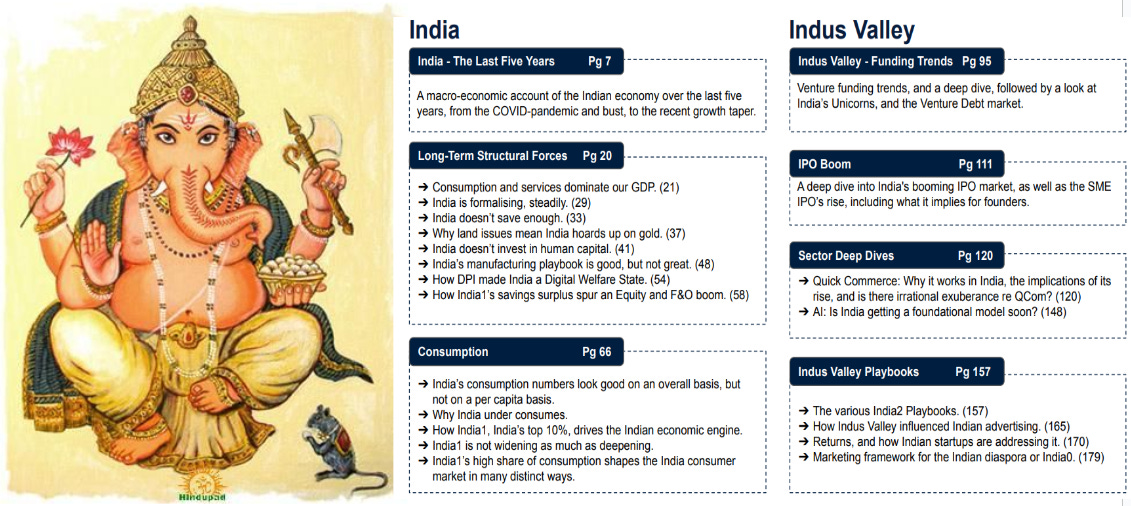

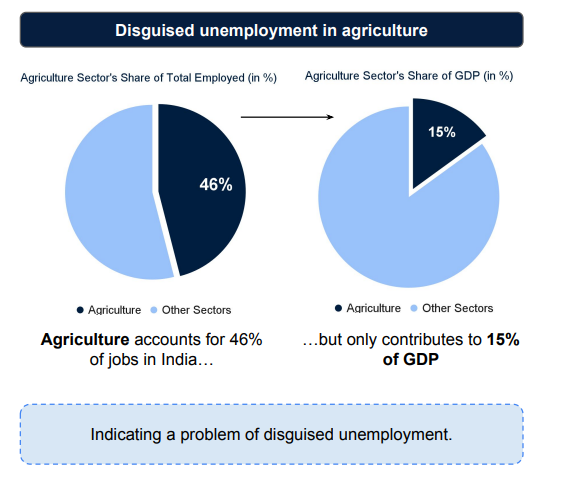

In contrast, ‘Bharat’ appeared twice and ‘agritech’ went missing in the 2024 Indus Valley report. In the 2023 Indus Valley Report, ‘agritech’ murmured through a lone mention of ‘Waycool’ under B2B e-commerce platforms, and in the 2022 Indus Valley Report, it purred through a lone mention of eNAM under Public Digital Infrastructure. In July 2024, Blume released a separate “Building Agritech for India” under “niche topics”. I am here looking at the omission of agriculture from a generalist India narrative. Sure Services sector dominates the Indian economy. But why ignore Agriculture’s Labour Force Split, especially when it contributes to 46% of Labour force?

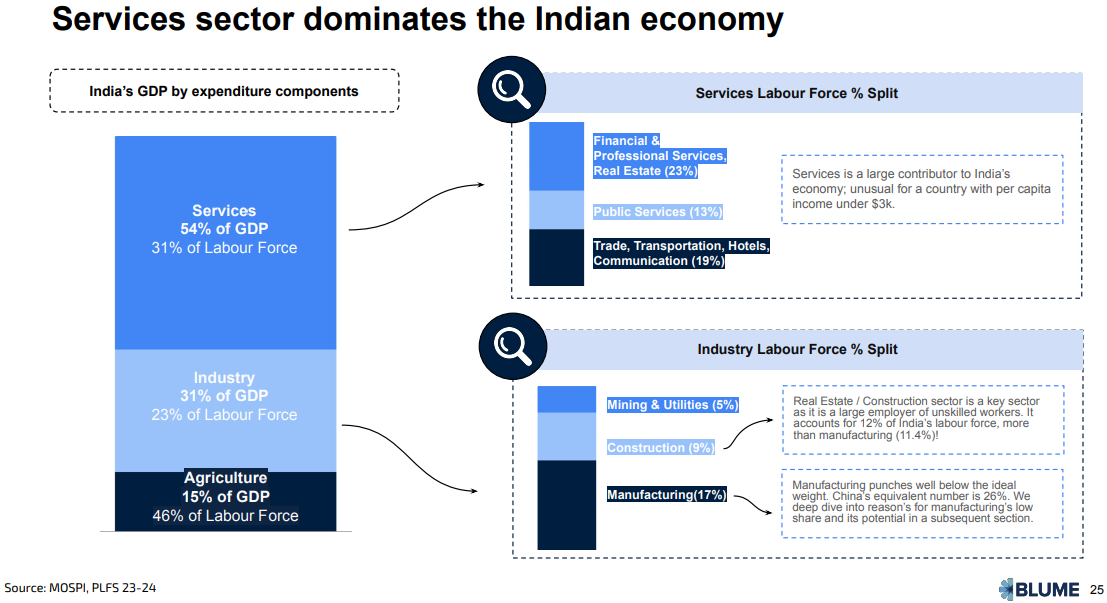

Had Agriculture been included within the scope of Indus Valley Report, it would have perhaps added a lot more nuance to IVR’s broad stroke narrative that “India is formalizing steadily” captured through a) Increasing share of income captured in direct tax filings and b) Growth in registered GST payees.

As

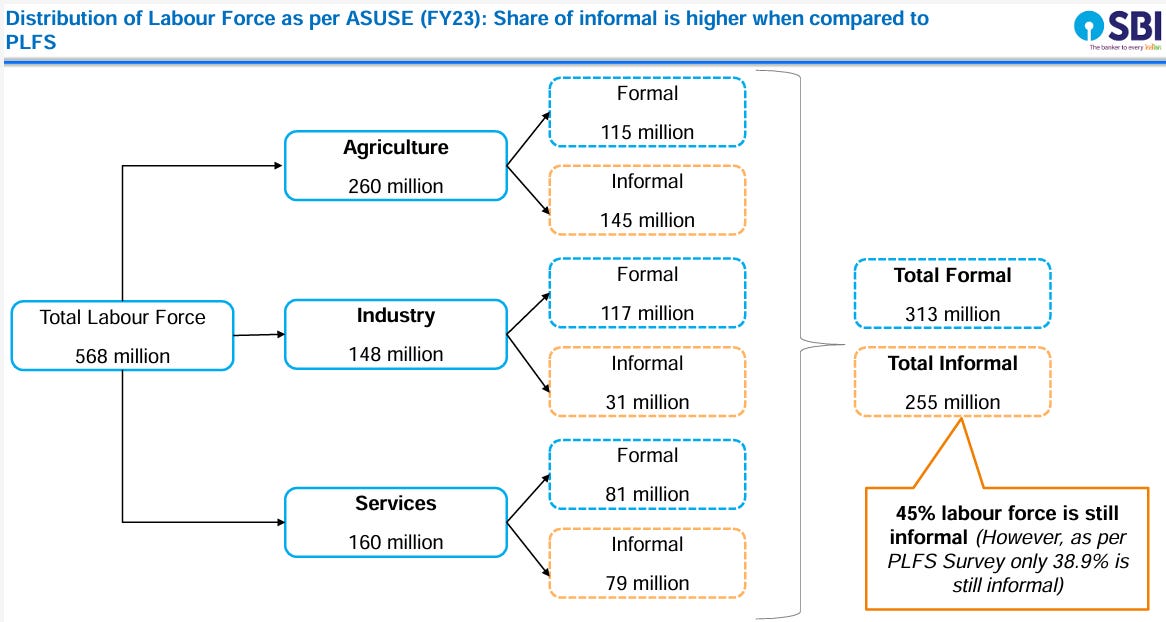

of Whole Truth Foods is perhaps wont to say, “It’s the truth. But, not the whole truth.”How can we argue that India is formalizing steadily, when 45% of the labour force2 is informal, with ‘agriculture (25.5%) and services (13.9%) accounting for 40% of the total workforce / 88% of informal workforce’?

Can we conclude that the economy is formalizing steadily when the economy is formalizing at a faster pace than labour economy?

Although Blume does acknowledge PLFS - Periodic Labour Force Survey 2023-24 (which reports 38.9% labour force as informal) while covering India’s Labour landscape, when you look at the 2021-22 data and 2022-23 data from ASUSE (Annual Survey of Unincorporated) Survey Enterprises, the messiness of India’s tryst with the formalisation of economy and labour force starts to reveal itself.

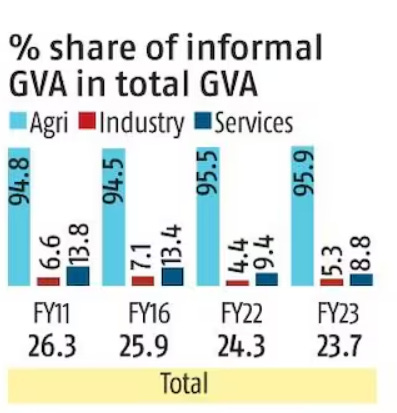

If we put this messiness into perspective, we discover an unsettling narrative backed with data: While the share of Industry and Services have formalized steadily, agriculture has more-or-less remained the informalized elephant, with the share of informal agriculture in total GVA rising from 94.8 per cent in FY11 to 95.9 per cent in FY23.

This has radioactive repercussions in how we understand India. If agriculture stubbornly remains informal economy despite seven decades of agrarian reform, what on earth is happening?

Why have seven decades of agrarian reform failed to formalize agrarian economy? Or is the nature of beast such that it would always remain an informal beast at large?

How would have the Indus Valley Report turned out, had they included the informal beast of Agriculture within their research scope? Thanks to my occupational bias, this question kept running in my head as I pored through the 188-slide report.

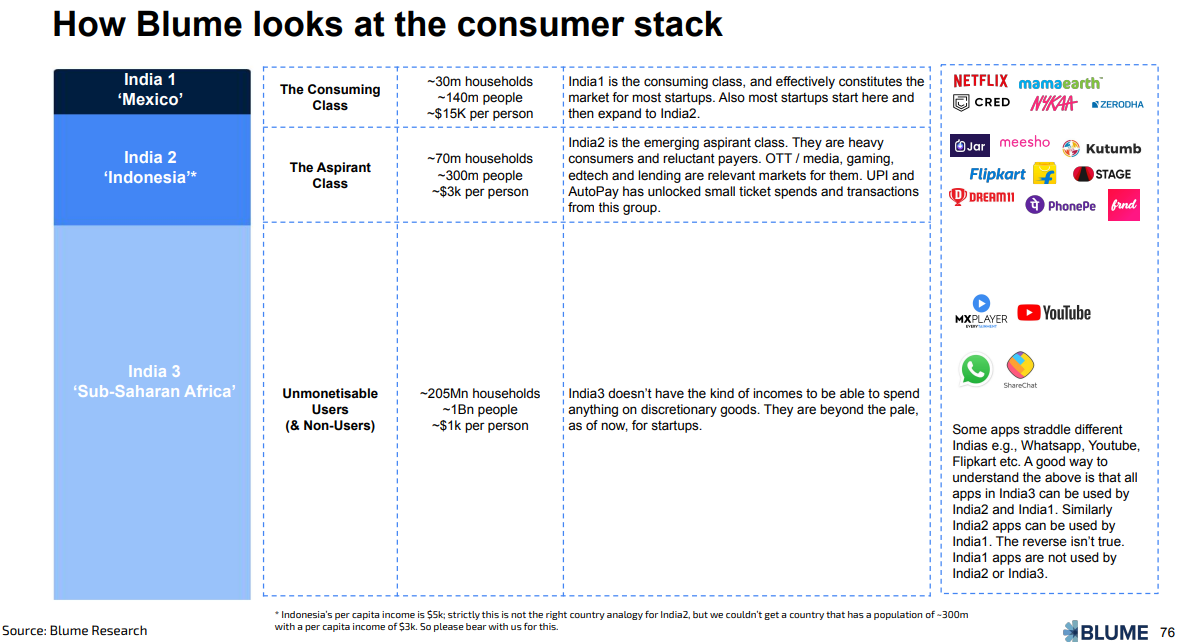

The fulcrum of their report is the classification of India’s consumer stack into three Indias.

While the report goes into greater depths about India 1 and India 2 playbooks, the report goes silent about India 3, lapping them under an uncharitable ‘Sub-Saharan Africa’ label.

Although Sajith has made it categorically clear that “India3 is not Rural”, India3 triggers subconscious association bias with Agriculture and my biggest concern is the disservice such generalist VC narratives do in influencing LPs and other fund managers about the incredible wealth possibilities that remain in Indian agriculture.

With the omission of Agriculture in the IVR scheme of things, besides highlighting ‘disguised unemployment in agriculture’, it brings in my mind a fundamental question: What constitutes development? Is development a linear path from India 3 to India 2 to India 1?

As I’ve written earlier, if this were indeed the case, India’s farmers wouldn’t be cross-subsidizing the low-cost food we take for granted, keeping food inflation at check at the cost being eternally trapped in India 3.

In 1954, Arthur Lewis wrote a seminal article called Dual Economy, in which he proposed that a developing country has two sectors.

Lewis proposed this model to suggest what now in hindsight seems plain common sense. Obviously, you shift the labour into the small capitalist sector, where it is more productive, and when capitalists are able to draw from “unlimited” supply of labour, they can expand without raising wages, thus leading to higher capital returns. Assuming that the capitalists are reinvesting, this can create a positive feedback loop of growth and eventually lift the entire sector from poverty and bring them onto mainstream economic development.

Today, even mainstream economists have acknowledged that Arthur Lewis models have become obsolete, when reverse structural transformation -India’s labour force are re-entering agriculture - is happening instead of textbook models of structural transformation - where farmers are supposed to exit agriculture as the country develops.

“Official Periodic Labour Force Surveys (PLFS) show the farm sector’s share in India’s workforce decreasing from 64% in 1993-94 to 48.9% in 2011-12 and further to 42.5% in 2018-19, but subsequently going up to 46.2% in 2023-24.” - Harish Damodaran

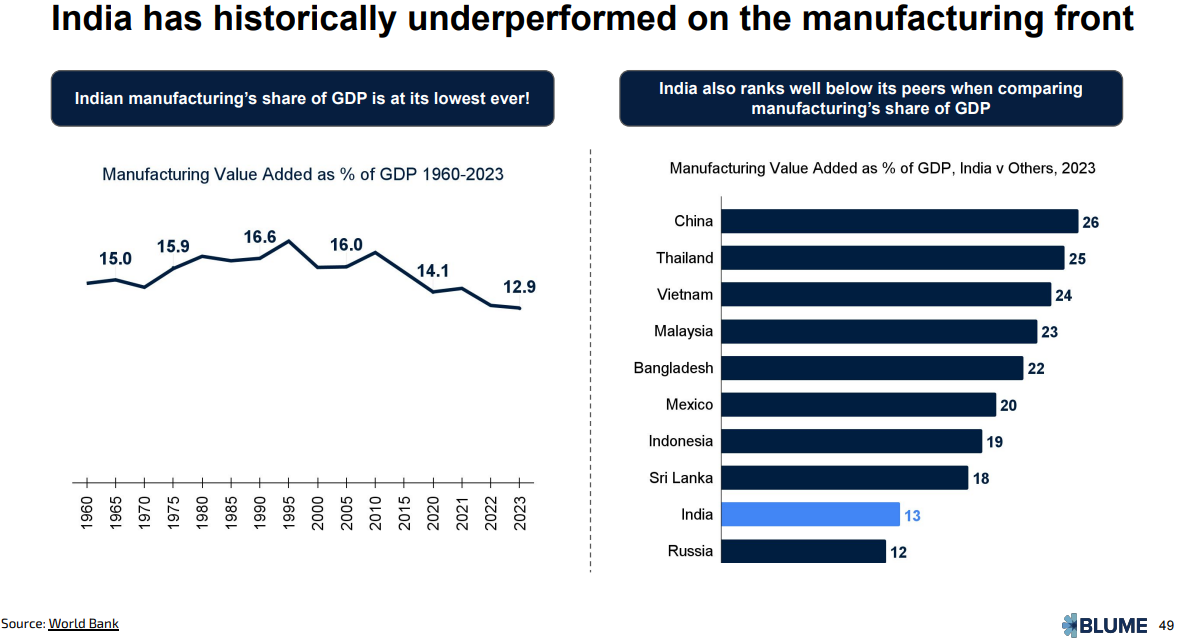

Why is Reverse Structural transformation happening in India? As IVR accurately notes, India’s manufacturing playbook hasn’t discovered its full potential.

“Manufacturing’s share climbed initially from 10.4% in 1993-94 to 12.6% in 2011-12, only to come down to 11.4% in 2023-24. The latest 2023-24 PLFS report reveals the 11.4% share of manufacturing in the total employed labour force to be below that of construction (12%), trade, hotel & restaurants (12.2%) and “other services” (11.9%).” - Harish Damodaran

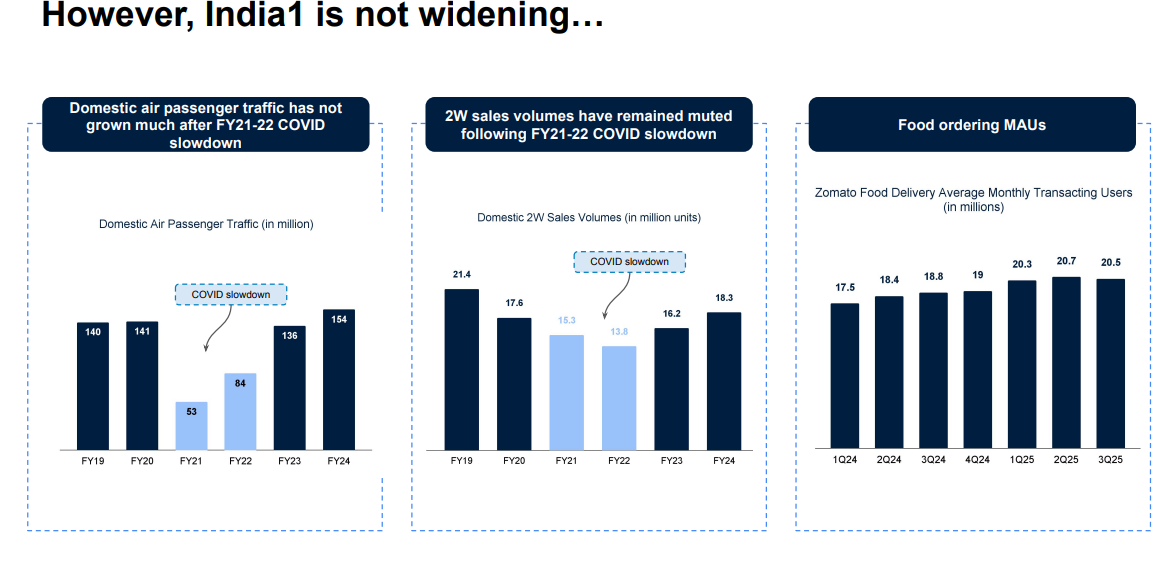

Although the team at Blume make a perceptive observation that ‘India 1 is not widening as much as it is deepening’, the underlying nature of their India 0-1-2-3 model seems to suggest inevitability of ‘structural transformation’ when there is evidence on the ground for the same.

What happens when we rethink the inherent assumption encoded in IVR that agriculture is a burden in this country? What happens when we rethink “Agriculture accounts for 46% of the jobs in India, but constitutes only 15% of GDP” as an opportunity?

Had Sajith and his team included a slide on India 3 playbook, they could have pointed out, as I’ve written earlier at length, Diversification as a key strategy in how a significant section of India3 is moving towards India 2.

At a macro level, you can categorize Indian Agriculture into four buckets a) Field Crops (Cereals, Oil Seeds, Pulses, Cotton, and Sugarcane) b) Horticulture Segment c) Livestock Segment d) Fisheries.

Between 2011-2023-24, a) Field Crops have grown at 1.5 % b) Horticulture has grown at 4% c) Livestock Segment has grown at 6-7% d) Fisheries have grown at 9-10%. (Data Source: Ramesh Chand, Niti Aayog at the recent NABARD Post-Budget Webinar).

In other words, India 3 Farmers are diversifying from their traditional cropping patterns towards horticulture, livestock and fisheries and slowly moving towards India 2.

With the 45% India’s labour force still remaining informal labour force, we see a peculiar paradox of India suffering from massive labour shortage, despite agriculture constituting 46% of the jobs in India.

Walk around any farm and ask any Indian farmer what is her biggest challenge? She will point out the burgeoning labour costs and how difficult it is to find skilled labour, leaving the women and the elders in the family to work as unpaid labour to cope with the labour shortage.

Agriculture and India 3 has its share of challenges and opportunities and, if not for anything, for its sheer damn size, cannot be written off if we are serious about India’s future and our collective aspirations to become the third largest economy in the world by 2030 with a growth rate of 6-7%.

Would Climate Change throw a spanner at this plan of becoming 5 trillion economy by 2030? Can we expect to see adequate coverage of Agriculture, Climate Change and India 3 in the generalist 2026 edition of Indus Valley Report? I hope:)

IVR has inspired me enough to put out the macro and micro view of Indian Agriculture and Indian Agritech. I will publish “State of Krishi” Report soon with proprietary datasets of Indian agritech startups. The wheels have been set in motion. Watch out for this space!

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Agribusiness Matters”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.

Neem Karoli Baba was a spiritual guru Steve Jobs was eager to meet. This quote is from Steve Jobs’s biography written by Michael Moritz.

The data comes from SBI Research’s Excellent Report The Dichotomy of Formalisation based on ASUSE Report 2022-23