Three Reasons You Should Call "Fourth Agricultural Revolution" Bluff

2023 is here and it's time to take down beloved sacred cows without causing any harm to the embattled livestock sector.

A Word from the Sponsors

Editor’s Note: I am experimenting with sponsored ads from select advertisers. If you are interested in doing content sponsorship experiments with focused 30K+ food and agribusiness audience of Agribusiness Matters, do reach out.

Noom is an interesting online experiment to rediscover health through understanding why we eat what we what. In my ongoing biological experiments to deeply understand the co-ops called human body, I have found this question extremely powerful. Some of you may want to check it out.

Dismantling A Platitude Called “Fourth Agricultural Revolution”

If you’ve spent time in the conslutting business (not a typo), you would know that management consultants (I used to be one) and analysts (I am currently one) are in the business of creating ‘platitudinous aphorisms’ that swing through crests and troughs in the marketplace of ideas.

What is a platitudinous aphorism?

Take a phrase like “Fourth Agricultural Revolution”. It fits the textbook definition of a platitude (from the French word ‘plat’, flat) - those 'which say nothing, but hide behind the weight of’ pompous words like “revolution”, drawing its sustenance from another meaningless platitude, “Fourth Industrial Revolution”

When the basis for value creation is becoming counter-industrial, shifting from physical, tangible assets to intangible assets like networks and data, how on earth can we take a phrase like “Fourth Industrial Revolution” seriously?

Of course, one wo(man)’s platitude could very well be another wo(man)’s profundity. And so before you dismiss my claims as outlandish, I present to you my evidence.

Reason #1: Agricultural Revolutions are rarely linear and unevenly distributed.

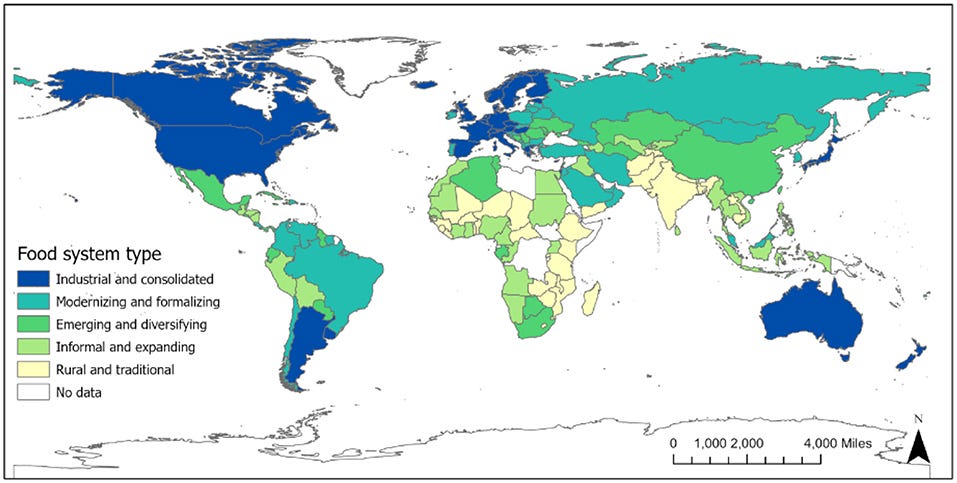

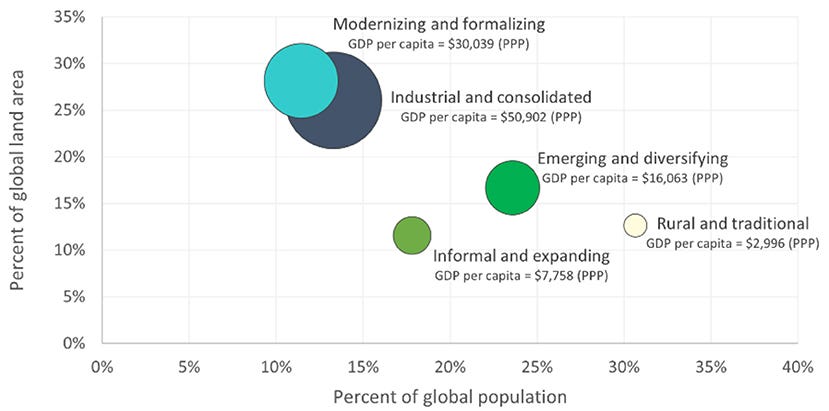

To argue my case, I am going to leverage and draw insights from a recent paper that presents a neat bird’s eye view to categorize 155 countries’ food systems (covering 97% of the world population, 93% of global land area and 97% of GDP) into five categories with four indicators.

These are the exhaustive, mutually exclusive five food system types that largely make up the world’s food and agricultural system.

rural and traditional

informal and expanding

emerging and diversifying

modernizing and formalizing

industrial and consolidated

As you can imagine, regions of the world are characterized by multiple food systems. For instance, you can find all five food systems in the Middle East; four in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Now if the tall claims of agricultural revolutions were indeed true, how did we end up in a state where Industrial and consolidated food systems and modernizing and formalizing food systems only account for 13% and 11% share of the global population respectively (despite larger share of global land area)?

If you want a snapshot of the current state of our global food system, this is a good bird’s eye-view approximation.

Let’s peel this one layer deeper.

If the claims of agricultural revolutions were indeed true, it would imply that both the food systems - industrial and consolidated food systems and modernizing and formalizing systems - are indeed desirable goals for the rest of us living in, say, India, which has a rural and traditional food system.

Now, what happens when we peel this assumption layer further?

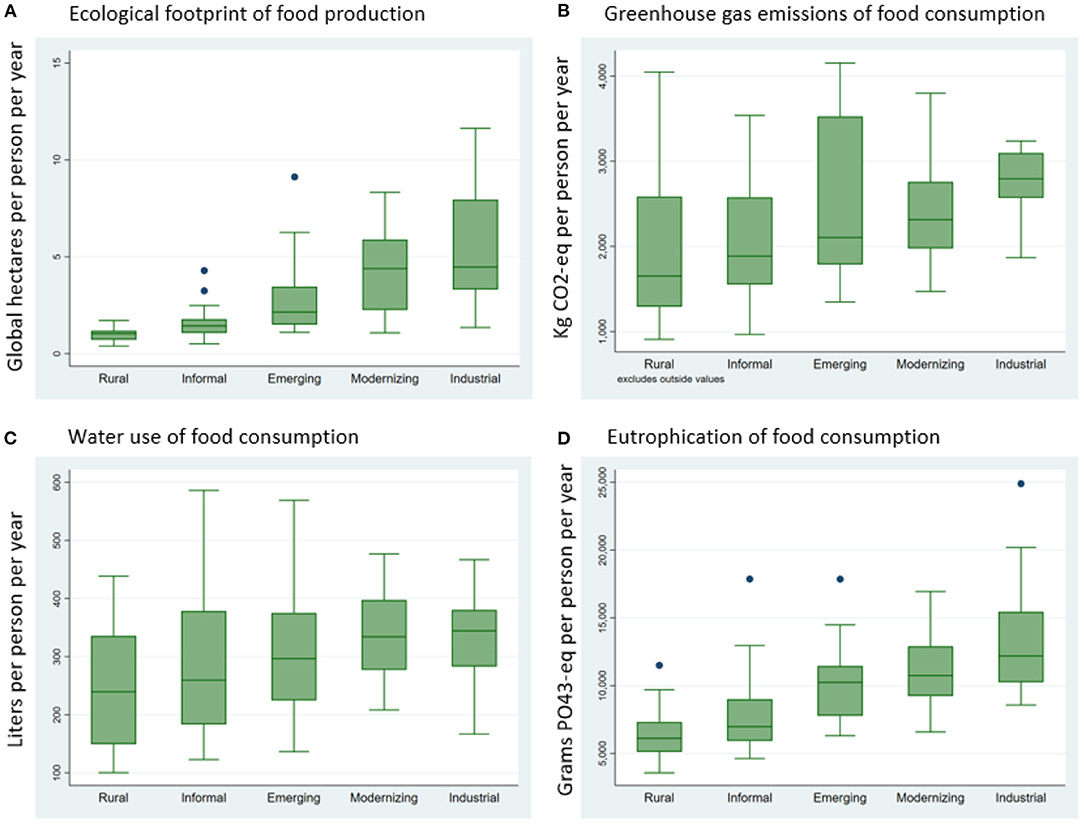

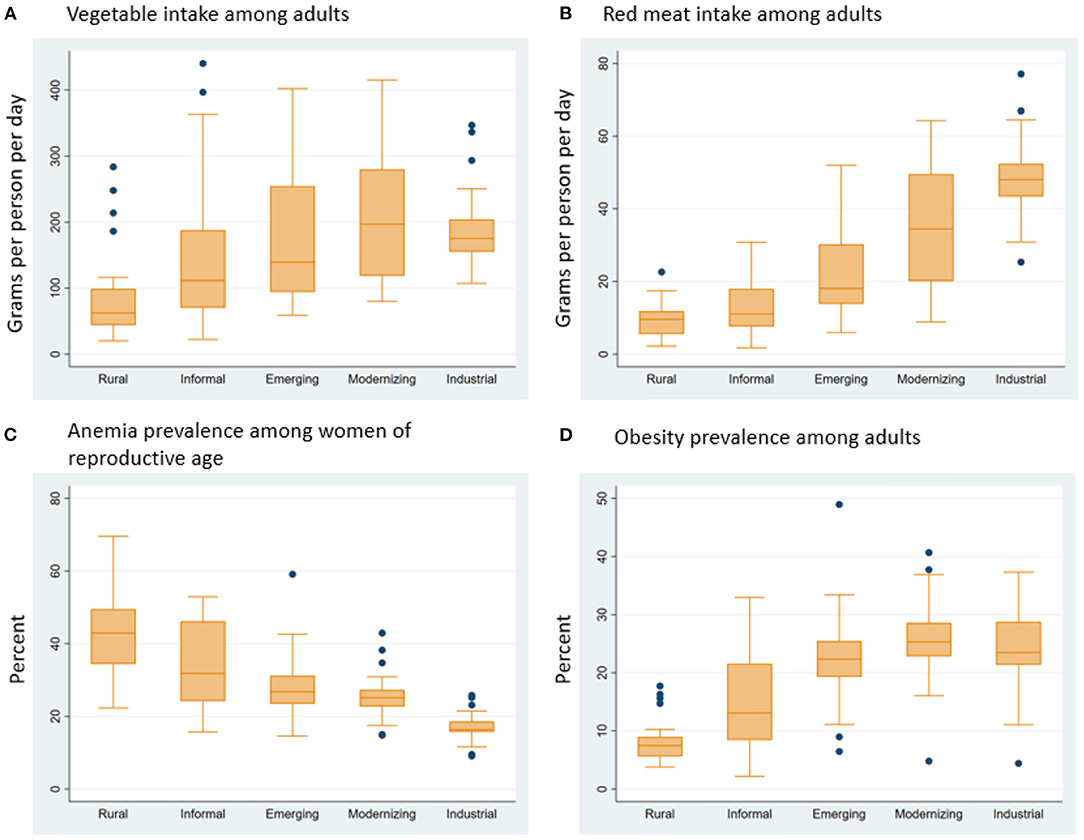

Is it worth considering the industrial and consolidated food system as a desirable goal when it has the highest ecological footprint among other food systems and there is enough evidence of high prevalence of obesity for those living in these food systems, thanks to easy access to ultra-processed foods (Gomez and Ricketts, 2013)?

Can you imagine the staggering ecological implications when ‘nearly one-third of the global population [that] lives in a country characterized as having a traditional and rural food system’ aspires towards an industrial and consolidated food system?

Of course, if you meditate on the above chart slowly, you would realize that the truth is much more complicated than passing moralistic climate ethics judgment on countries with industrial and consolidated food systems.

“Water withdrawals in more traditional food systems are primarily directed toward grains, though poor irrigation technology can result in higher evaporative losses, which may explain why many countries in rural, informal, and emerging food systems still have high water use per capita from food consumption” (Jägermeyr et al., 2015)

When countries talk of their aspirations for global food systems, more often, they imply the GDP per capita typically associated with that system, even though the relationship between ‘income growth and structural changes affecting the food system is not as straightforward as they may seem’.

Sure, Agricultural Revolutions are rarely linear, but how unevenly distributed are they?

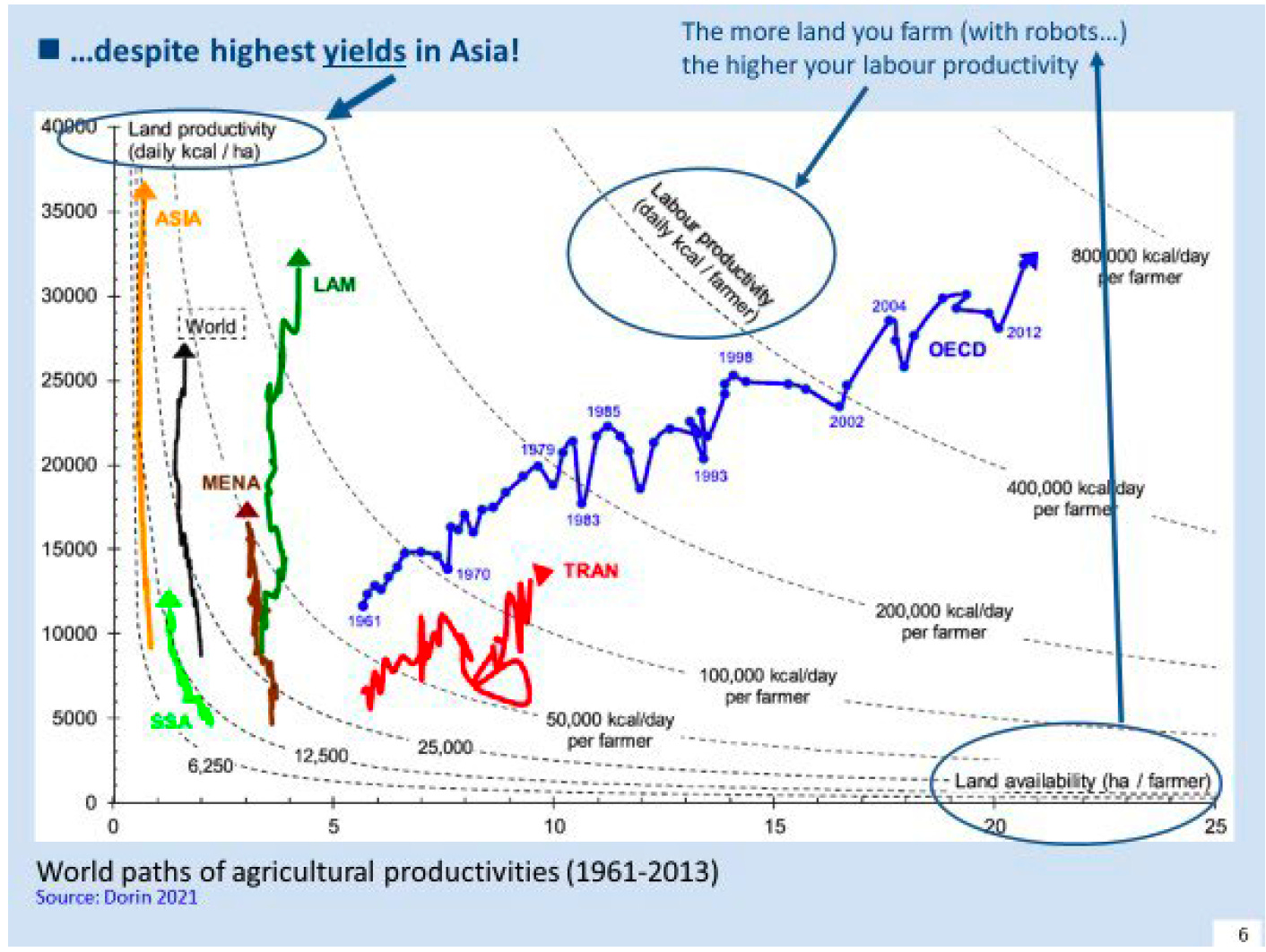

And as I have explored in greater depth earlier, agricultural revolutions have further increased the gap in labour productivity, despite high yields and overuse of agricultural technologies.

“Over half a century, you can see that the labour productivity of OECD farmers has risen from 66,000 to 658,000 kcal/day on average, a tenfold increase, while in Asia it has only increased from 7,900 to 25,000, barely three times.”

Now, why did we let this happen? Allow me to present my second reason.

Reason #2: Agricultural Revolutions have willy-nilly created the Agritech Death Cycle in the traditional agricultural value chain.

As an agritech consultant who makes a living advising agritech strategies to my clients, what I am doing in these spaces to take down sacred cows of techno-optimism might seem masochistic.

Let me be honest. My relationship with technology is thermostatic.

Just as it is the job of a thermostat to ensure the stability of the temperature in a room by introducing heat in response to too much cold or vice versa, my job as an agritech consultant is to dampen hype in the agritech room of irrational expectations towards technology and pitch for technological solutions in another agricultural room of political agricultural economy.

With that disclaimer put, let me get to the core of my attack against hollow claims of agricultural revolutions.

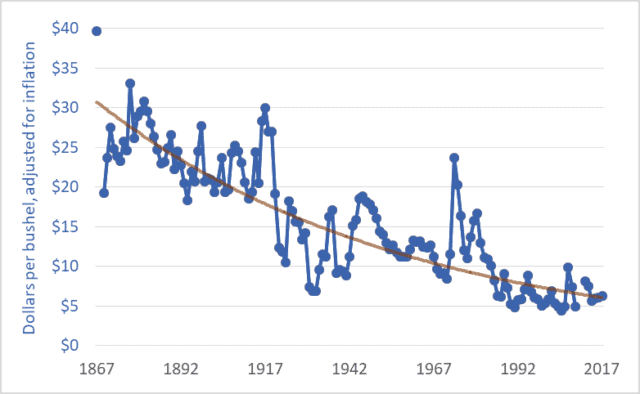

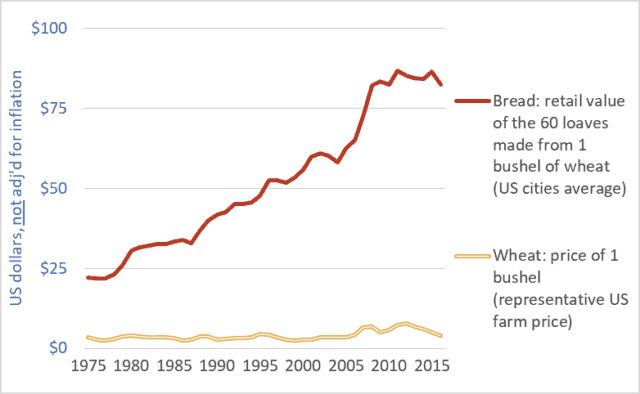

If you want to understand what agritech death cycle is, why it happens and how we can overcome it, first take a look at how wheat prices have been declining over the past 150 years.

I am selecting wheat here as there is more data .You could very well present a similar case using rice or maize. There is enough evidence of how rice and wheat monocultures have replaced rice-pulses intercropping system in India and other countries

The central question is WHY.

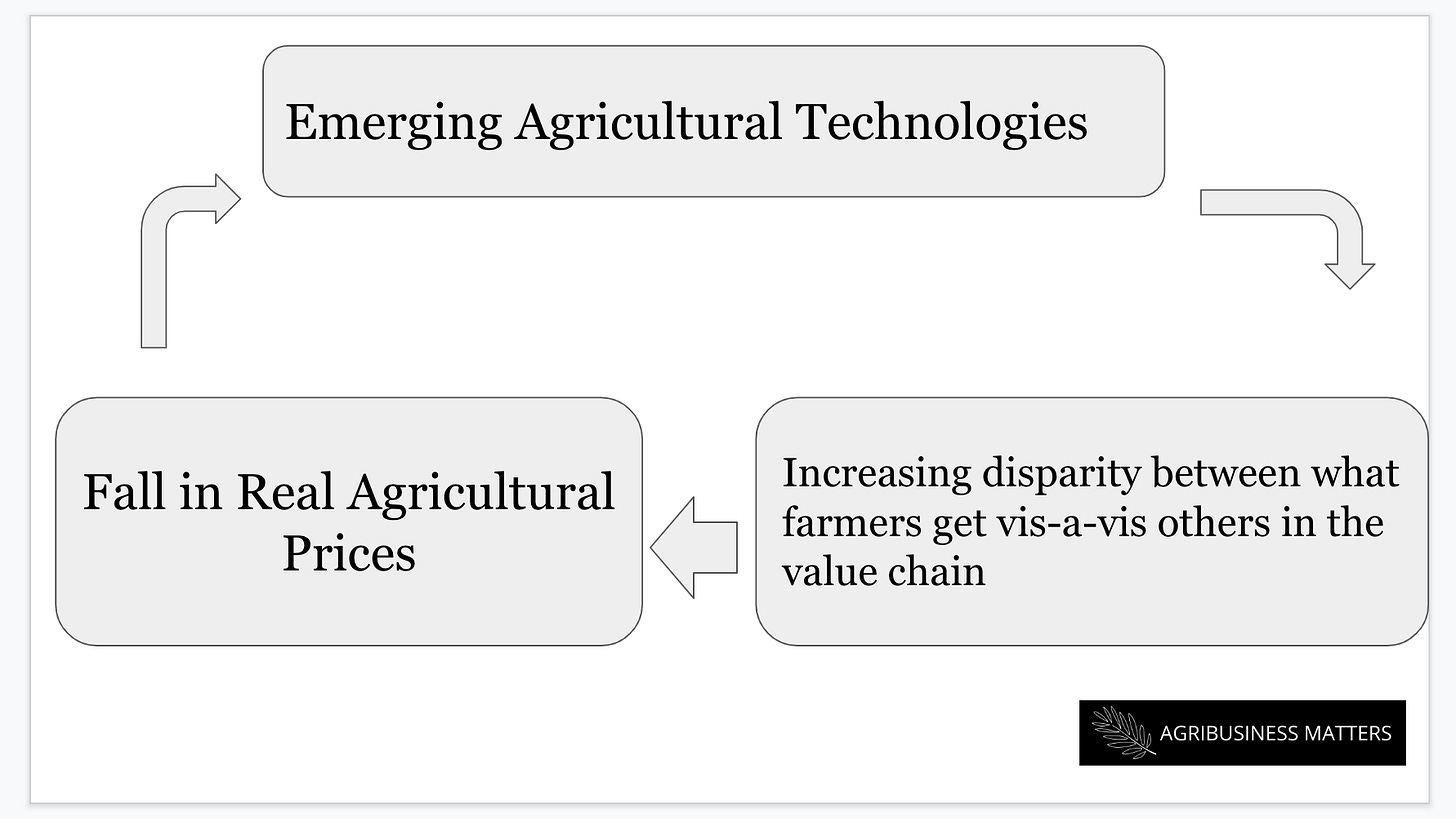

Whether we like it or not, emerging agricultural technologies that birthed the green revolution have led to increasing disparity between what farmers get for their produce vis-a-vis other actors in the food value chain, which further led to a decline in agricultural prices leading to a vicious cycle.

This is the Agritech Death Cycle.

Before we understand how to come out of agritech death cycle, it is important to understand the disparity between what farmers get vis-a-vis other food actors in the value chain. This disparity is unfortunately a global phenomenon. It is happening in the US,

It is happening in the EU.

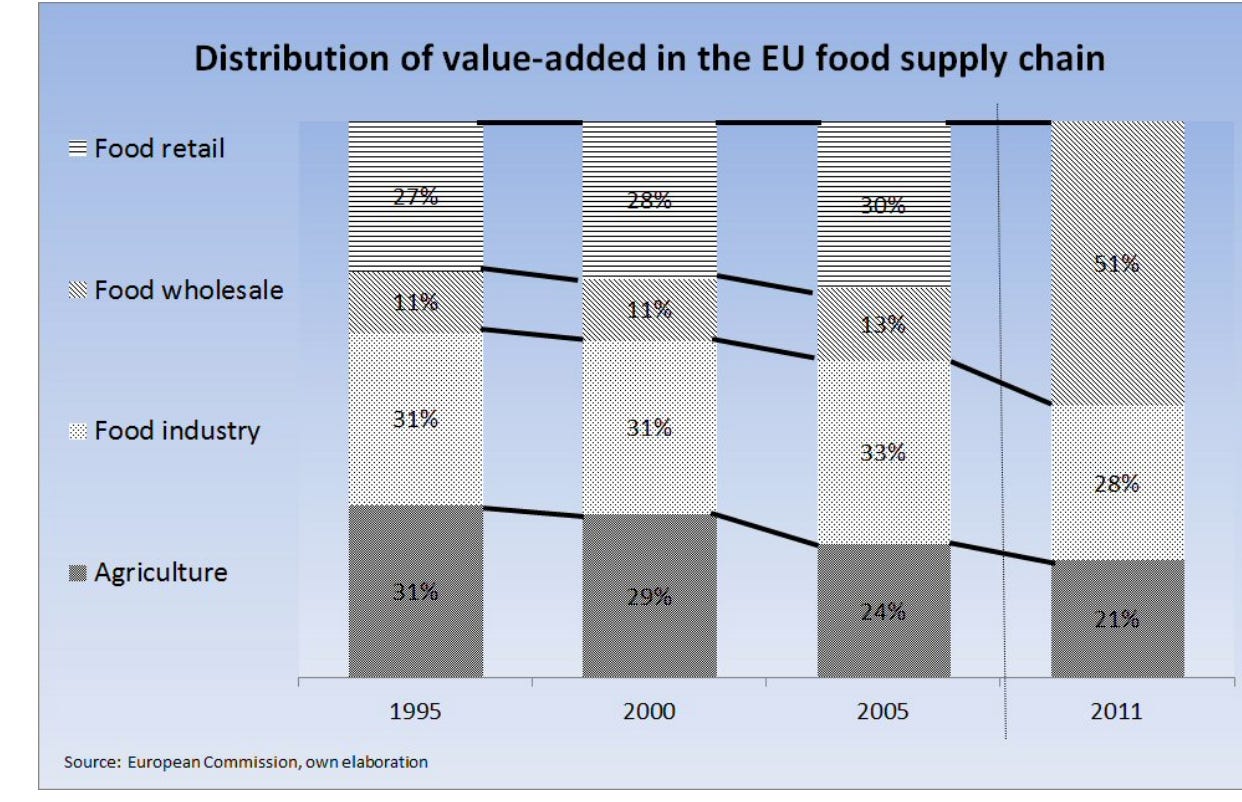

When the European Commission was asked in parliament to provide details on the average share/percentage of the final price that farmers receive for their produce, relative to the share/percentage received by other actors in the food supply chain, they found that the value-added for agriculture in the food chain dropped from 31% in 1995 to 21% in 2011, mainly in favour of other food chain actors.

If you contrast this number with 28% for the food industry and 51% for food retail and food services, it is evident that the highest value addition occurred in the supply chain far away from the farmer.

When this vicious cycle continues with newer emerging agricultural technologies that don’t change the entrenched underlying value chain structures, we sadly see the agritech death cycle repeating.

How to break out of the agritech death cycle?

To find a way to break out of the agritech death cycle, it is important to understand the idea behind ‘Farmers Share of Consumers Price’. Because, as you can see, the only way to break out of the agritech death cycle through technology is to disintermediate the traditional value chain and build newer value chains that connect farmers directly to market through technologies of logistics and automation.

And that’s hard and is precisely the bet of investors worldwide trying to crack this problem..

Let’s now look at the third and final reason.

Reason #3: Naive claims of agricultural revolutions are errors in understanding Goodhart’s Law

Before you dismiss me as a sensationalist cherry-picking data to sut my narrative, it is important to give due credit to agricultural revolutions where it is needed.

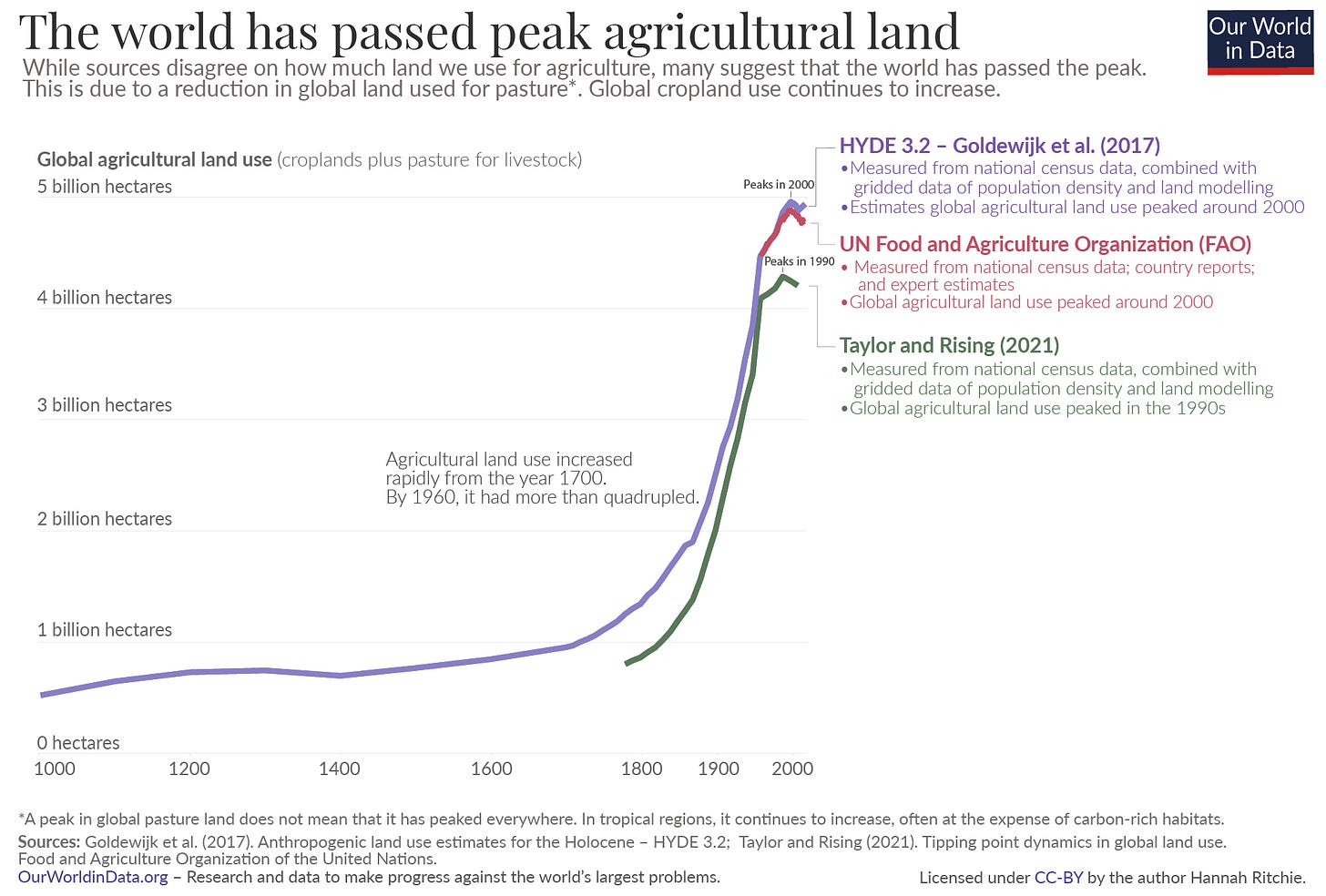

Three different data sources claim that the world passed peak agricultural land use around the 1990s and 2000.

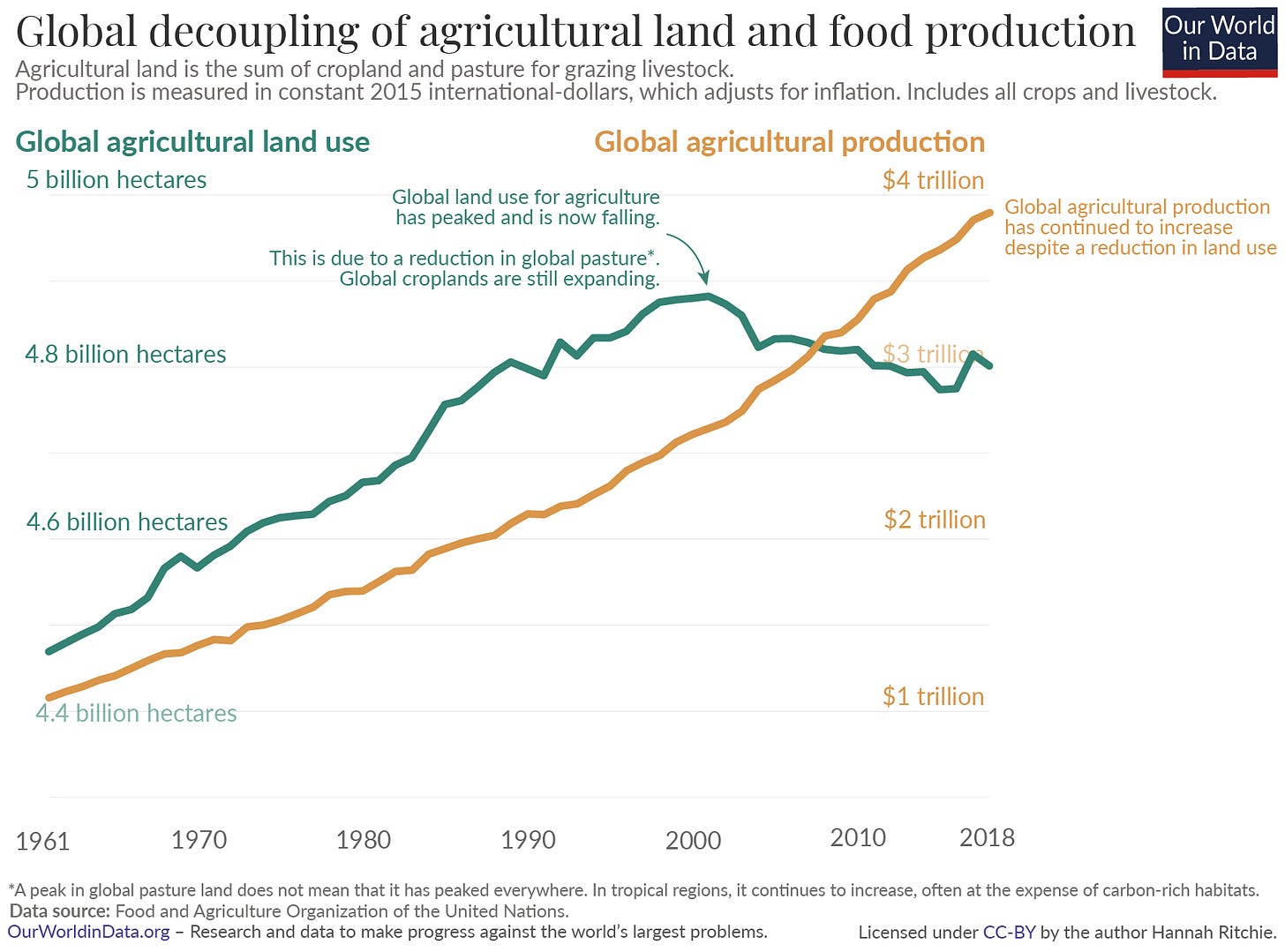

And despite that, there has been a decoupling of agricultural land and food production.

“While global agricultural land – the green line – has peaked while agricultural production – the brown line – has continued to increase strongly, even after this peak.” (Source)

All of this couldn’t have happened without agricultural revolutions and the underlying agricultural technologies.

Today, circa 20233, when Climate Change is a mainstream concern, with 2023 promising to herald an era of famine and food insecurity, when we have already crossed five out of 16 climate tipping points, the crucial existential question remains: What is the price we are willing to pay for this global decoupling of agricultural land and food production?

In the year 1975, British economist Goodhart coined Goodhart’s law in response to Margaret Thatcher’s trigger-bound monetary policy.

Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.

Here is a plain-speak translation: When a measure becomes a metric, it ceases to be a good measure [Strathern’s variation]

Here is a more pertinent translation for those of us dreaming of better food systems:

“Anything made explicit will sooner or later be gamed for survival purposes and that need will corrupt practice and people (Snowden’s variation)

Because green revolution focused on quantity (more yield per unit area) and not on the nutrient-density of the produce, global decoupling was possible as we produced cheap food using wheat-rice monocultures and intensive livestock farming in feedlot operations.

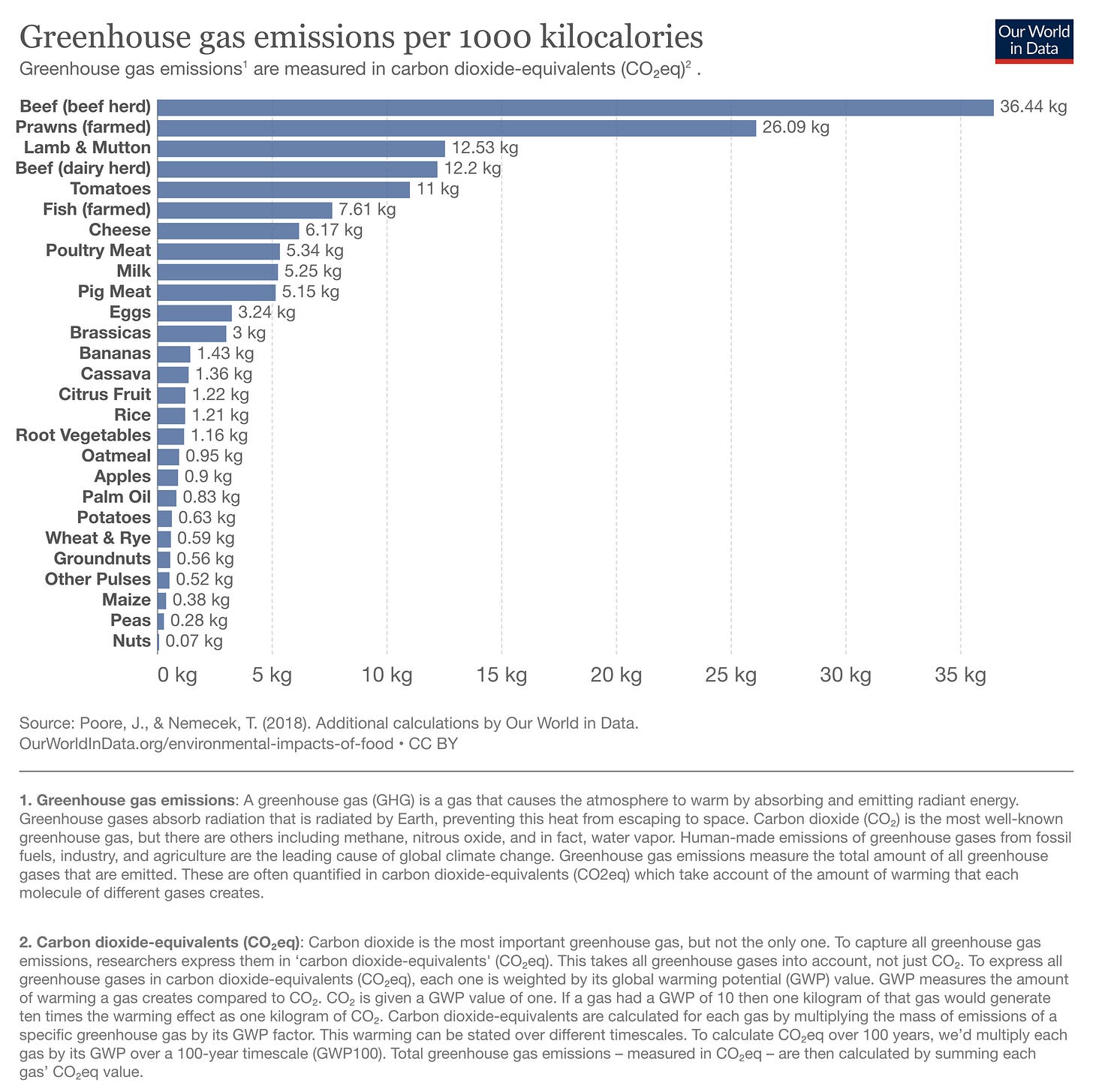

When you meditate on the graph deeply , you would notice that the solution to sustainably feed the world without eating the planet lie in the bottom parts of the chart which provide the enough diversity required for health and nutrition ,

We can’t afford to have measurement systems that only measure kilogram/output without measuring nutrient density of the food produce. When you compare diet, nutrition and health outcomes across the food system types, you would realize the complexity of the task involved.

Vegetable intake is higher in countries wth formalizing and modernizing food systems and and the same time, increase in obesity prevalence is also taking place in ‘the earlier stages of food systems’.

If we are looking at a possibility of a real agricultural revolution, we have to look at two questions seriously.

Can we make healthy diets affordable?

Can we build measurement systems that track the nutrient-density of the produce along with the quantity of the produce?

Perhaps, those are good aspirational goals to start with for those of us working in food and agricultural systems in 2023. Are we ready to start 2023 and put our heads down to work?

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Agribusiness Matters”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend