Unpacking the #FarmBills Controversy: No Country for Middle Men

The Final Part in Two-Part series to make sense of the political chaos surrounding the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill.

Hello friends,

My name is Venky. I write Agribusiness Matters every week to talk about Agribusiness and Agriculture in the nick of transformation.

Author’s Note:

After I had written the first part, this essay came in between a planned vacation and I had to stop thinking about this essay for a while. Well, almost. Sincere apologies for those who patiently waited for this.

I am writing this more for those outside agriculture than inside. I am hoping though it would also be useful for insiders to see the industry challenges in a new light. Regular readers of this newsletter will have to bear with me for repeating some of the points I have made before.

My deep gratitude to Jagadeesh Sunkad for the deep conversations over the last few weeks, which inspired this piece. Although you can read this article independently, I would suggest you start from First Part, where I have laid the context of my analysis of #FarmBills.

In the First Part of the series, I set the context by exploring

Why Agriculture is Politics?

How Common Man’s Perception of Agriculture belies the ground reality?

How Agriculture Works Differently in the ‘Developing’ World vis-a-vis ‘Developed’ World?

Why Free Market is a Myth in Agriculture?

How do we understand the key factors which have shaped Indian Agriculture in its present course of evolution?

Can Free Markets deliver what it promises to do in Indian agriculture?

In this second part, I want to cover

What are the problems which the FarmBills want to address?

How has it set out to address those problems? What are the reassurances it has offered?

What are the unintended consequences that could emerge from the way it is attempting to solve these problems?

Chapter-4: A Cautionary Parable from Prussia

01/ In James C. Scott’s fascinating book, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, Scott examines a particular pattern of failure that kept recurring in various domains in the first half of the twentieth century, ranging from agriculture and forestry to urban planning and census-taking. He calls it Legibility.

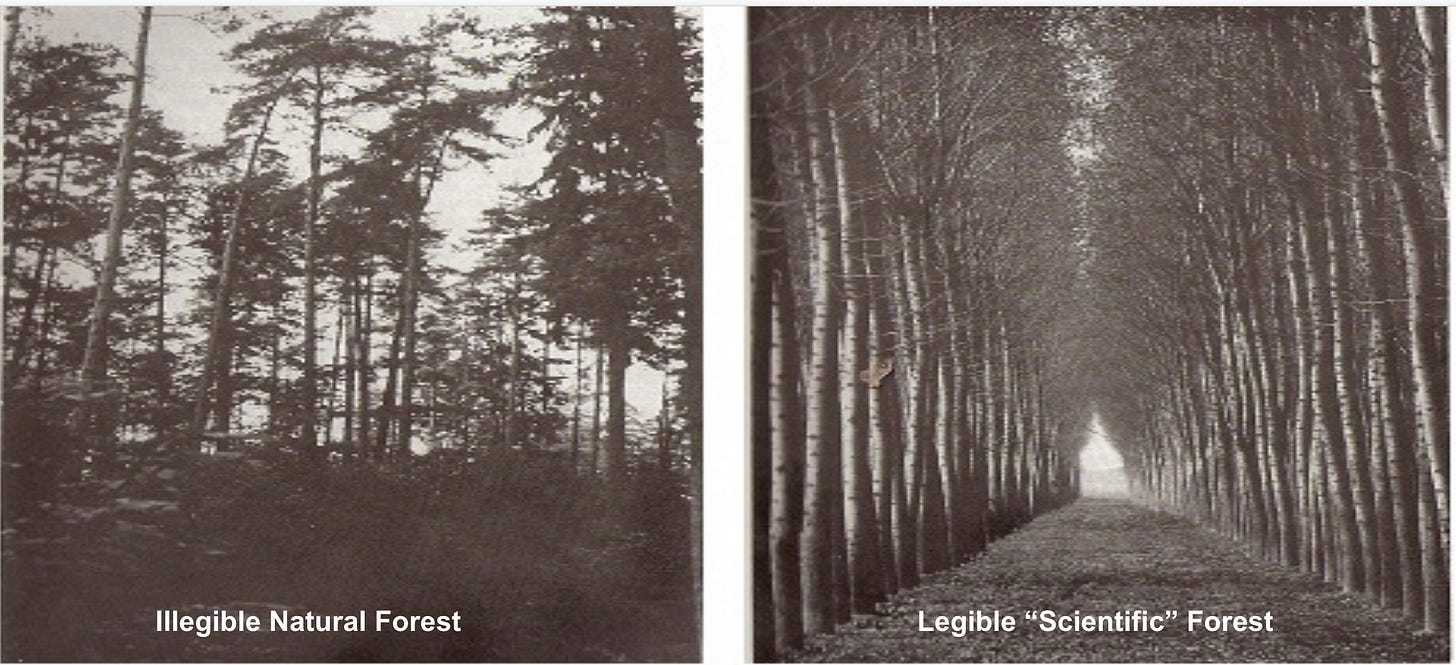

02/ Here is an image from the book that graphically and literally illustrates the central concept of “Legibility”.

<Image Credits: Ribbonfarm | Page 16-17| James Scott’s “Seeing Like a State”>

03/ Not many know that Scientific forestry originated in Prussia and Saxony in the late-eighteenth century in response to the growing energy and construction needs that were largely met through timber.

04/ Scientific forestry, back then, made no qualms about its economic purposes. It defined an abstract “tree” as “a volume of lumber or firewood”. Its language served its purpose. Plants of value became crops. Species which competed became weeds. Insects which survived on those plants were stigmatized as pests. Trees of value became timber, while those which competed became “underbrush”.

05/ What happens when you see the forest as simple maximiser spreadsheet, tallying each tree and mathematically estimating their yields, when you grow the forest as “one-commodity machine”, planting timber in neat rows and clearing the “underbrush” regularly, thereby making the entire forest “legible” for the sake of administration?

06/ At first, it was a great success with very high yields in the first rotation. However, over time, negative effects showed. As James writes, “the whole nutrient cycle got out of order and eventually was nearly stopped....This represents a production loss of 20 to 30 per cent."

07/ The consequences were severe.

08/ Scott further writes, “An exceptionally complex process involving soil building, nutrient uptake, and symbiotic relations among fungi, insects, mammals, and flora...was apparently disrupted, with serious consequences.”

09/ I find this parable deeply illustrative. It tells you what happens when you disrupt an exceptionally complex and poorly understood set of relations and processes.

10/ Here is how this failure pattern typically plays out. Credits go to Venkatesh Rao who first introduced me this book through his blog, many years ago.

Look at a complex and confusing reality with intricate social dynamics.

Fail to understand all the subtleties of how this complex reality works.

Attribute that failure to the irrationality of what you are looking at, rather than your own limitations.

Come up with an idealized blank-slate vision of what that reality ought to look like.

Argue that the relative simplicity and platonic orderliness of the vision represent rationality.

Use authoritarian power to impose that vision, by demolishing the old reality if necessary.

Watch your rational Utopia fail horribly

11/ What makes this failure pattern timeless is the human instinct to project our subjective lack of understanding onto the domain we are looking at, as “irrationality”. We do this because we have a fundamental desire for legibility.

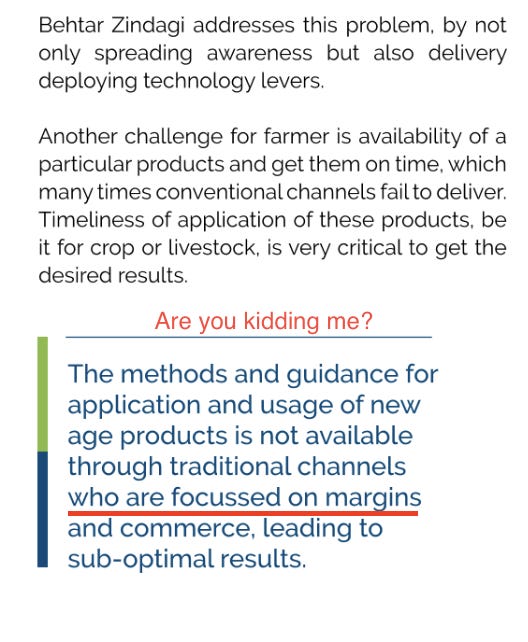

12/ Supply chain for agriculture has often been poorly understood. Specimen A:A Junior VC at its wit’s end, pontificating that supply chain has been “plagued” by middle-men who make 30-40% of wholesale prices.

13/ If the middle-men like “Arhatiyas” (commission agents) were indeed making 30-40% of wholesale prices regularly, by now, they would have started their own firms, formalizing their largely informal business activities. Why do the informal players (kaccha adat) still remain in business amidst formal players (pakka adat)?

14/ Here is a primer in case you are not familiar with the difference between the two. Kacha arhatiya cannot make any purchase in his own name from the farmer whereas Pakka arhatiya can purchase goods in his own name.

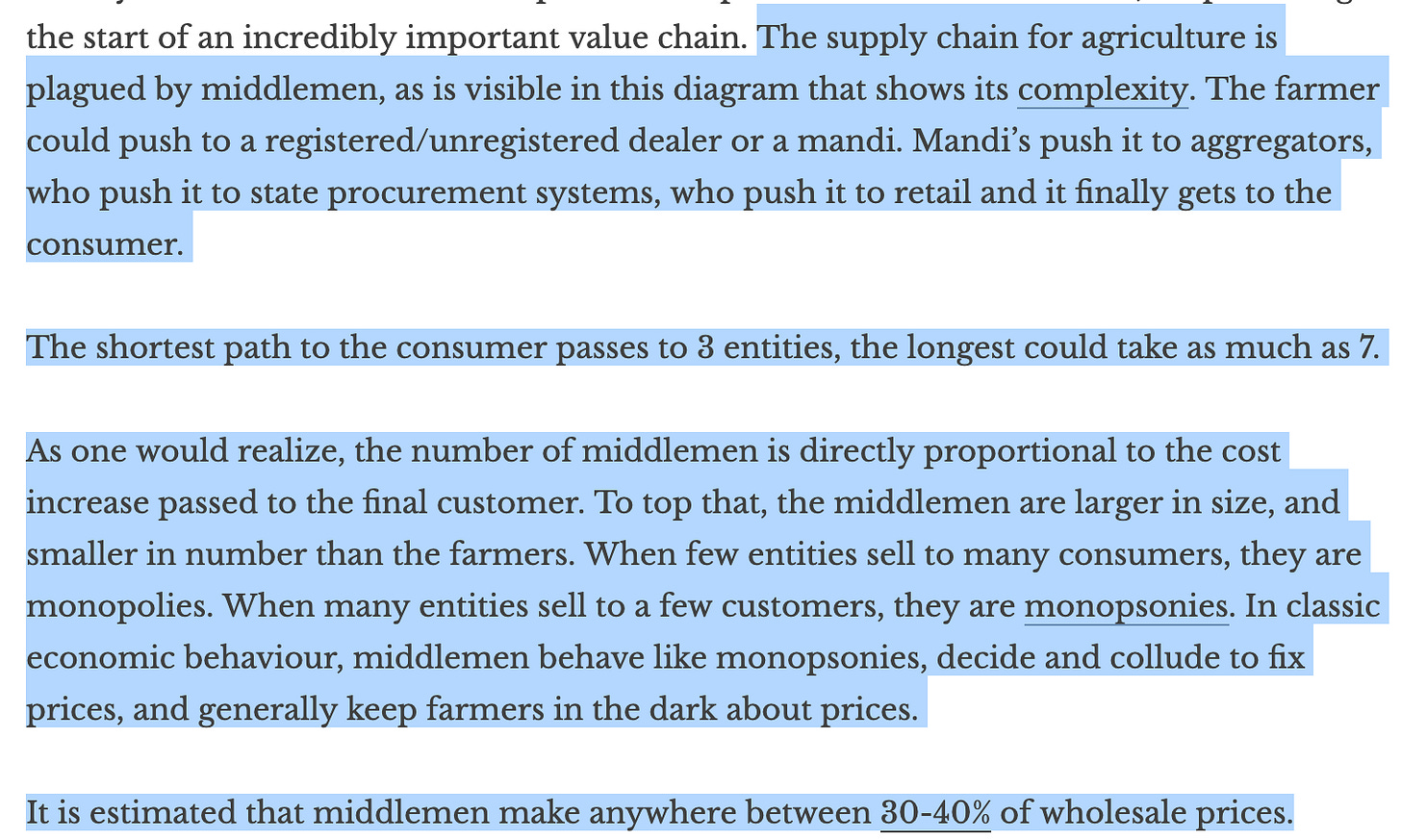

15/ Just in case you think that I am making the case for lack of comprehension of the supply chain of agriculture based on a single specimen of evidence, here is another.

16/ This one comes from Behtar Zindagi, as documented in a report titled“Agritech Innovations: Transforming Indian Agriculture" by the Foundation for Economic Development.”I couldn’t resist annotating this excerpt with my WTF comments.

17/ Are you seriously saying that Behtar Zindagi is not going to focus on margins because they are deploying technological levers? I am not the type to pick bones to fight. But, this is an extremely unfair characterisation of the middle-men.

18/ Essentially, what these agtech startup narratives are saying is this: Middle-men are the weeds in the agriculture supply chain who need to be removed if you want to make farmers profitable.

19/ Let’s be clear. I am not entirely dismissing the argument of middle-men behaving like monopsonies (where the price is determined by a single buyer), and therefore it’s time to dismantle those monopsonies.

20/ Sure, they have colluded at opportune times. But, is that sufficient enough to legally decree middlemen as “evil”, who, in PM Modi’s words, “unfairly loot the profit of farmers” ?

Chapter-5: Legible Agriculture Supply Chain

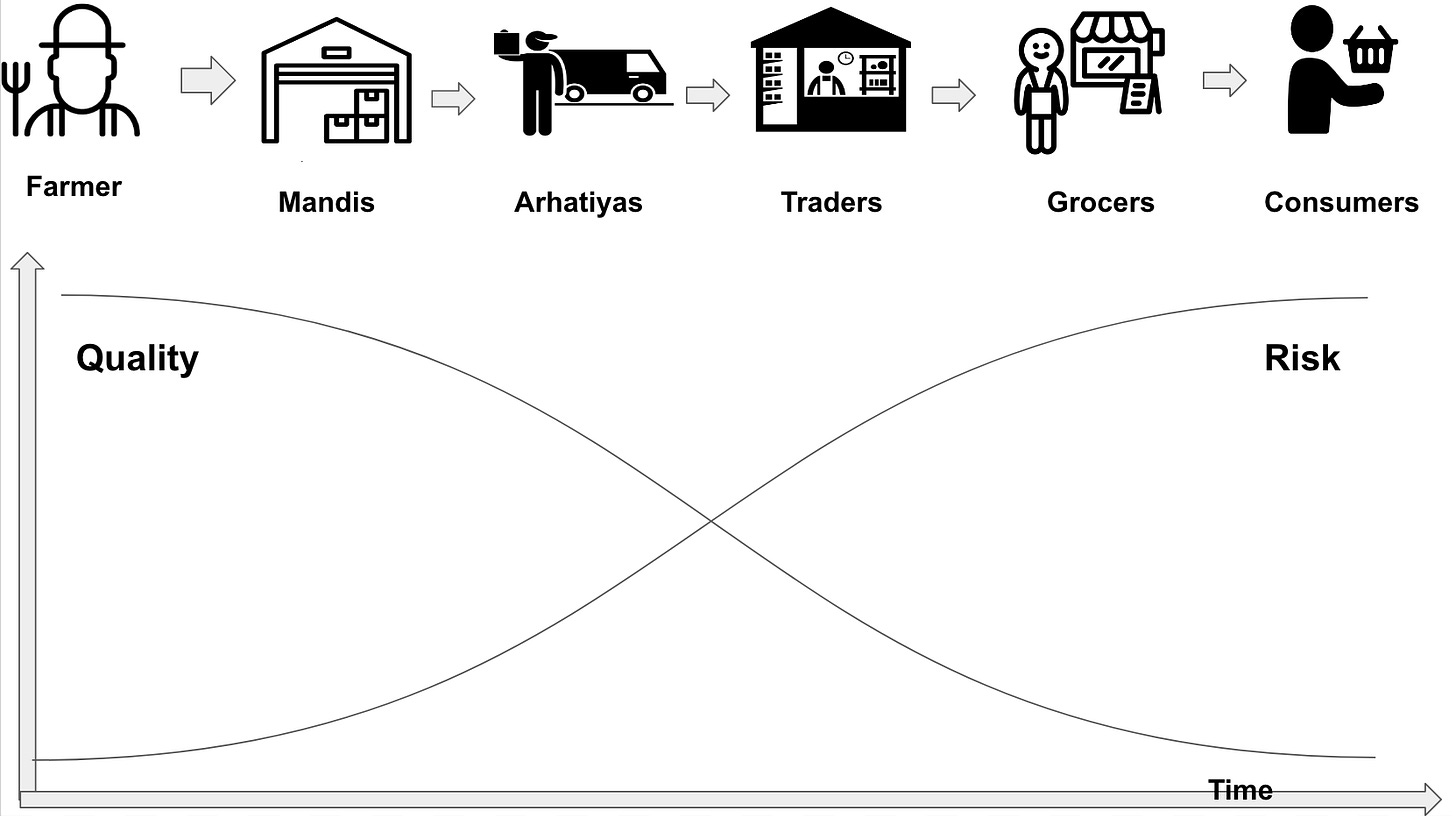

21/ What lies behind this urge to dream of “purer” and “direct” marketplaces without these middle-men? No prizes for guessing who is missing in the supply chain diagram drawn by “journalism for startups” firm, The Ken.

Image Credits: Traditional Agriculture Supply Chain Model: Analectic Research

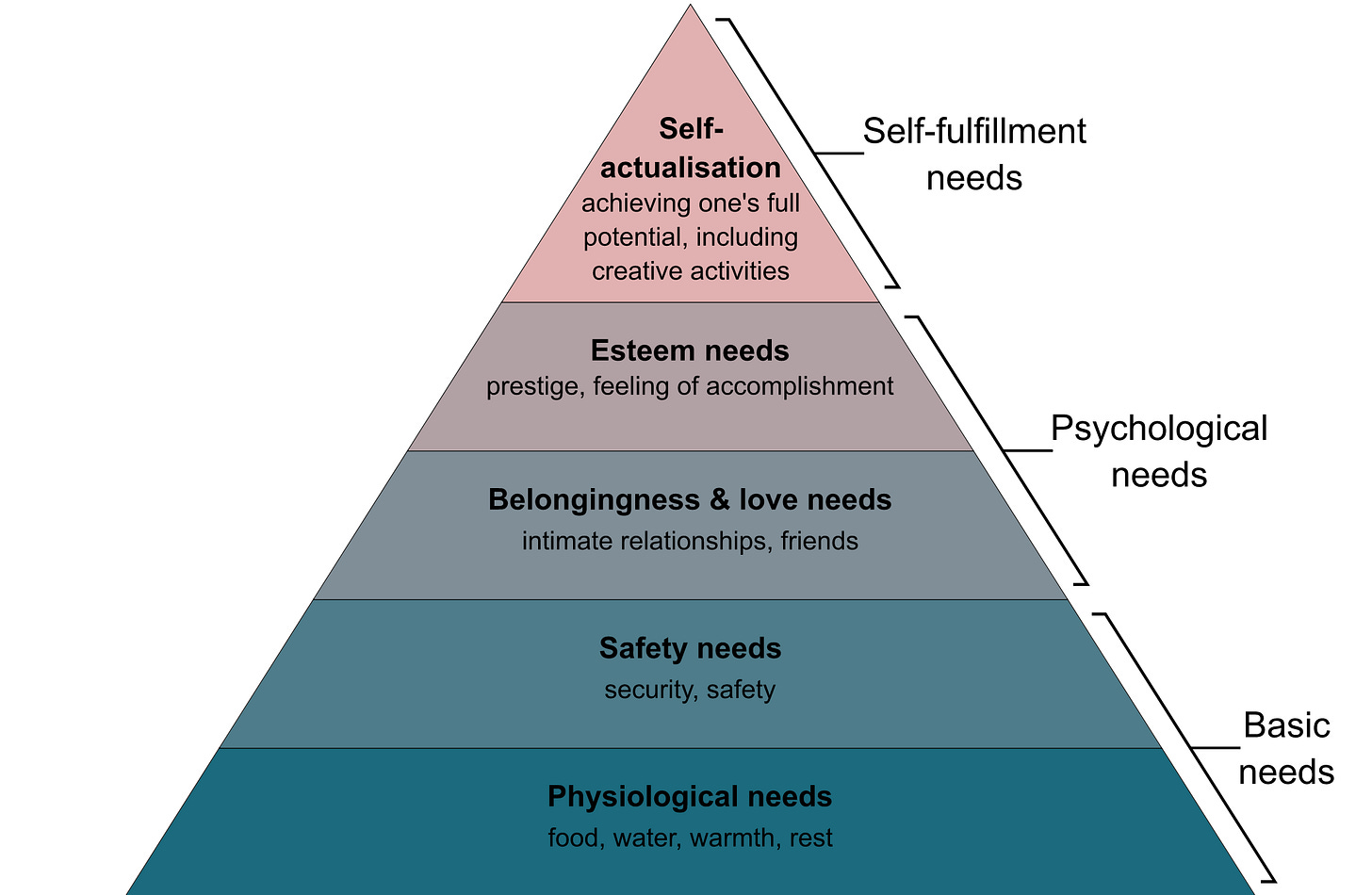

22/ At the end of the day, #FarmBills is envisioning a legible supply chain in agriculture, that is devoid of middle-men.

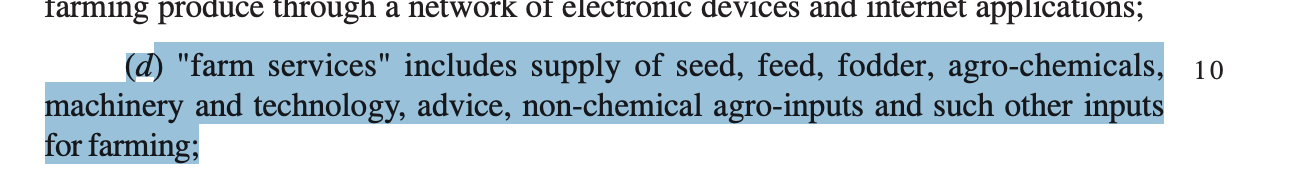

23/ If you read Section 2d of “Contract Farming Bill”, you will find this clause in an agri-input supply chain context.

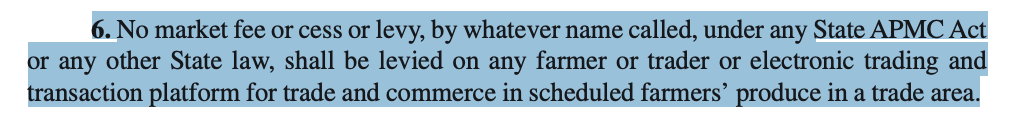

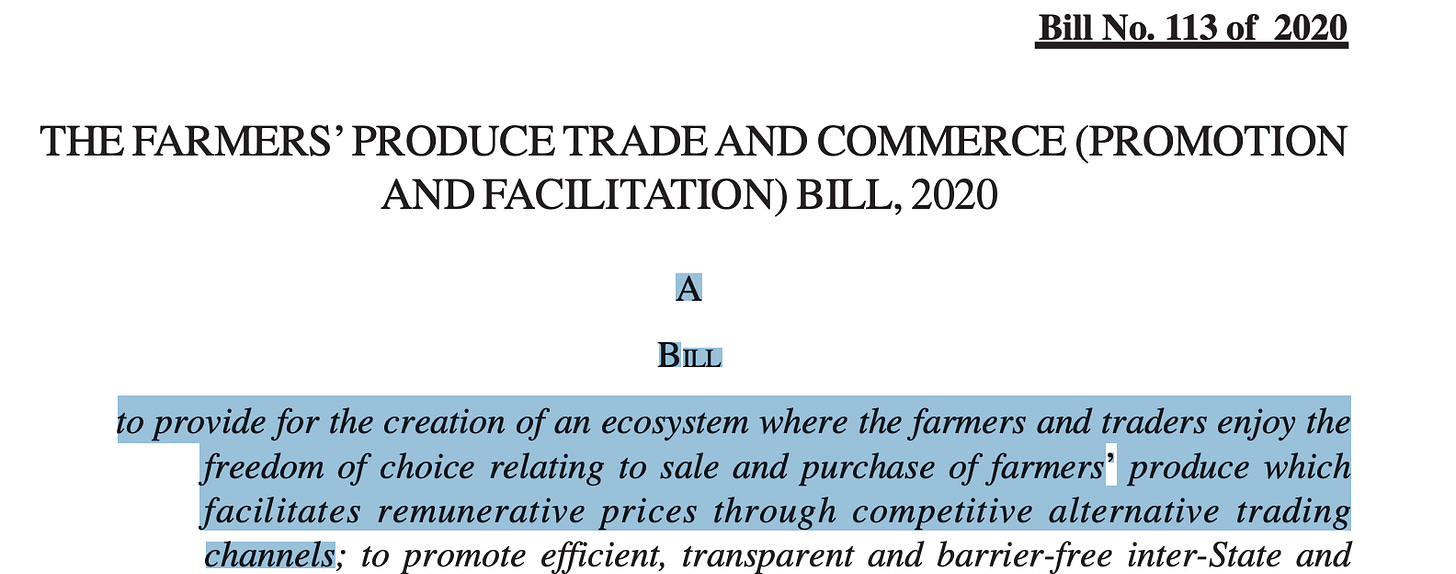

24/ If you read Section 6 of the “Let’s dream beyond APMC” Bill, you will find this clause in an agri-output supply chain context.

25/ If you are not able to connect the dots between the text I have quoted from the bill and my point about removing middle-men in the agriculture supply chain, here is an important primer to understand the politics happening beneath the scenes.

26/ As per the new bill, the complex and fragmented agricultural produce marketing landscape in the country has now been made “legible” by simplifying them into two market areas: ‘trade areas’ (under the new central law) and ‘market areas’ (under state APMC laws).

27/ Now, when you try to centralize the state subject of agriculture, naturally there is going to be resistance from the States.

28/ As soon as the Centre created new market areas where farmers could sell their produce without being subject to state regulations and fees, Rajasthan, by an act of legal abracadabra, redesignated all those new areas also as state-controlled markets. ‘

29/ The Central Govt.’s response is yet to be seen. You can very well expect other non-BJP states to respond like Rajasthan did, based on how the laws relating to agricultural markets have been framed in the respective states.

30/ In short, we are going to see a Tom-and-jerry-chase game to control the marketing of agricultural produce between the Center and the States.

31/ The Central Government has reassured that APMC market yards will continue to operate and can therefore charge market and licensing fees from buyers and arhatiyas (agents) for all transactions within the boundaries of the mandis.

32/ However, the fact remains that by removing cess in trade areas (under the gamut of the Center) while not removing cess in market areas (under the gamut of the States), you are sending a strong message to licensed traders: Please vacate your market yards!

33/ All of which begs the important question: What is the role of middle-men in the supply chain for agriculture?

34/ I would break this question into two parts. What is the role of middle-men in the agri-input supply chain? What is the role of middle-men in the agri-output supply chain?

35/ Picture this fantasy moment with me for a while. You are an agritech startup founder talking about Indian Agritech scene in a global investor forum. You are asked to describe middlemen in agri-input supply chain most objectively. It will be a hard challenge, I know. But, go on with my fantasy, will you please?

If you are honest, this would be the best one-line answer.

Middlemen offer hyper-local infrastructure to farmers to help them avail timely credit and inputs based on their contextual, relationship-driven understanding of farmers'cropping cycles.36/ Similarly, if you are asked to describe middle-men in the agri-output supply chain in the most objective manner, this would be the best one-line answer.

Middlemen offer real-time price discovery to farmers and bears the principal risk involved in assessing and procuring the produce of farmers and finding the relevant buyers for the farmers'produce. 37/ This is a very subtle point that is not often understood. Allow me to elaborate further.

Chapter-6: Understanding Principal Risk

38/ The moment the farmers’ produce has been harvested, the farmer is in a race against time. (We will talk some other time about how the game has been sloppily defined in the first place so as to make it a race against time). As the produce moves across the intermediaries in the journey from the farmer to fork, the principal risk increases in proportion to the likely decline in quality as the produce journeys from the farm to the fork.

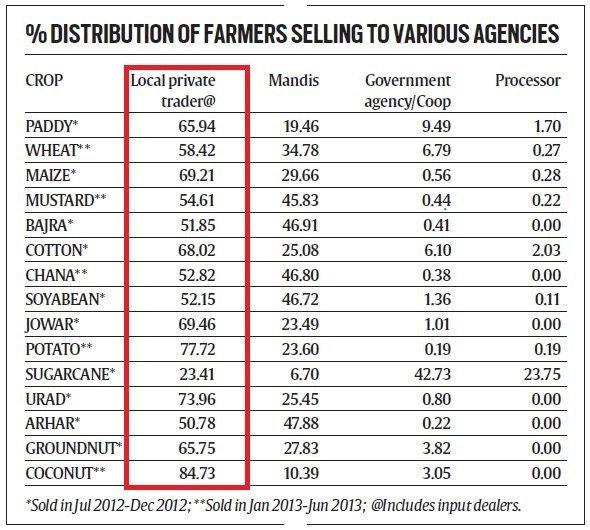

39/ Why else do you think farmers are selling their produce mostly to local private dealers, who are more often agri-input dealers? Compare this data point with that of mandis. You will understand what’s happening on the ground.

Image Source: Harish Damodaran | Indian Express | Data Source: NSSO - Some Aspects of Farming In India:

40/ It is these middle-men who are taking the principal risk for the farmers. They offer financing at a higher rate of interest, because they are with the farmer, not just when the prices go up, but also when prices go down.

41/ The high interest which the financing middle man charges covers a) Cost of Service involved in packing, grading and aggregating b)Cost of Risk in the journey from farm to fork c) Cost of Finance involved in selling the produce on credit to the buyer and paying the advance to the farmers.

42/ To talk strictly in economic terms, middlemen make double coincidence of wants unnecessary for farmers to sell their produce.

43/ This point about principal risk is crucial to this entire #Farmbills debate. Allow me to elaborate.

44/ Farmer trusts the recommendation provided by the agri-input retailer with whom he has transacted for several years, buying agri-inputs on credit from the retailer, thereby de-risking his investment in his business of agriculture.

You could tune into my discussion with Jagadeesh Sunkad for a deeper dive on this point in input side of things and output side of things.

45/ Now that he has taken credit from input/output dealer, he is assured that he has offloaded the responsibility to the retailer to buy out the produce, after harvest.

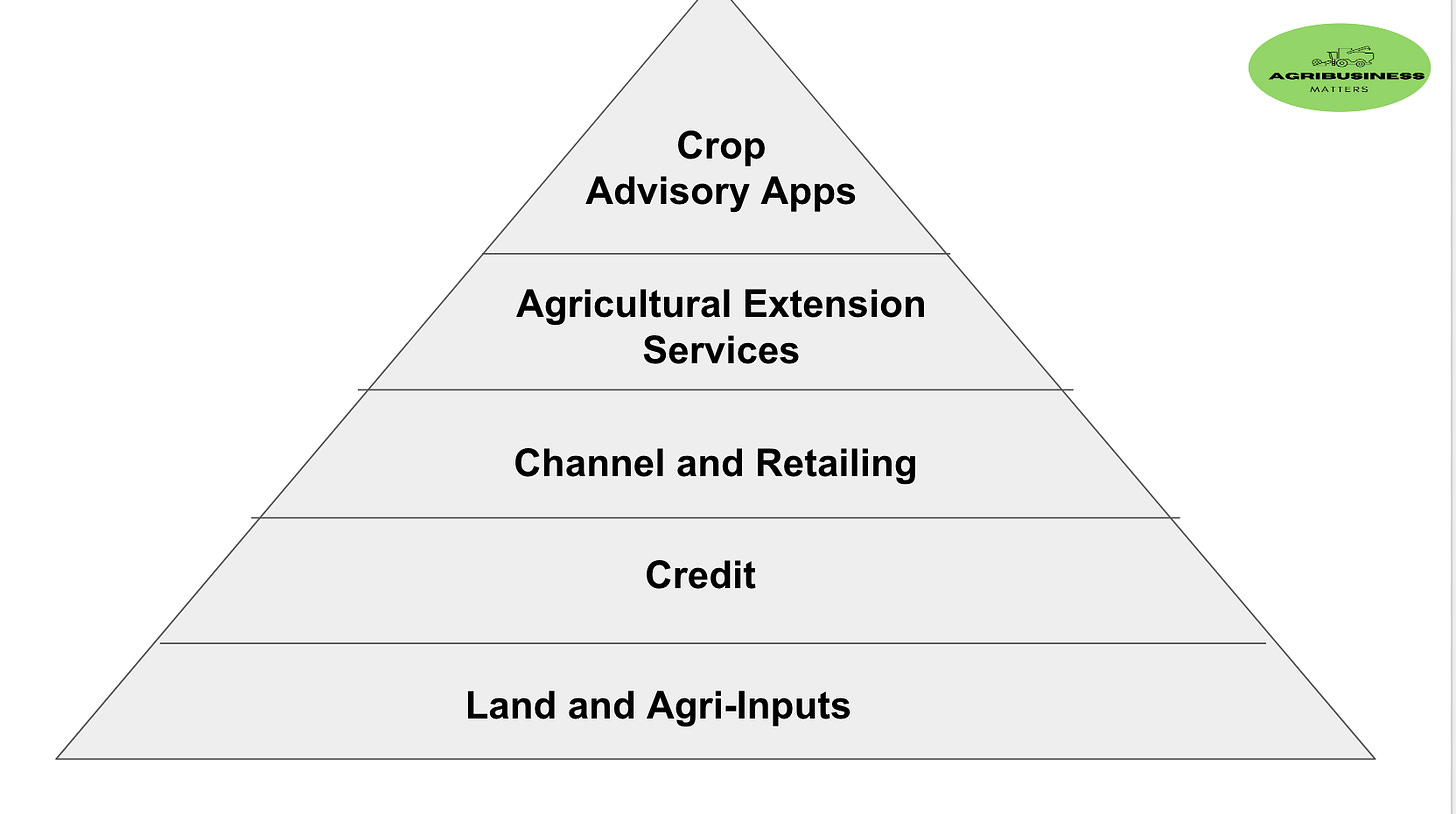

46/ Have you heard of Maslow’s Theory of Hierarchy of Needs? Likewise, if you draw Agri-Input Hierarchy of Needs for the average Indian farmer, this is what it looks like.

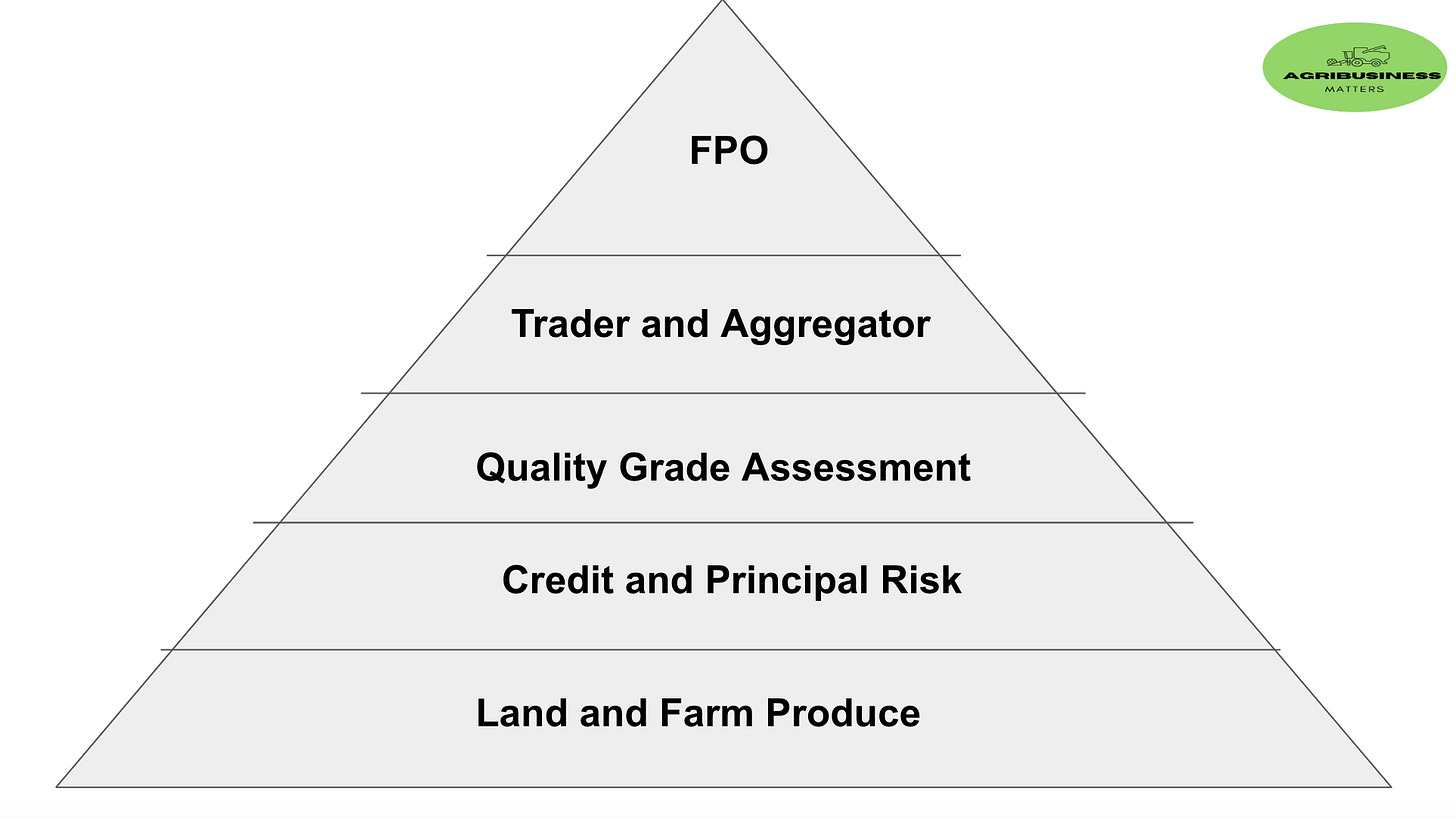

47/ Similarly, if you look at the emerging agri-output supply chain, the Agri-Output Hierarchy of Needs for the average Indian Farmer looks like this.

48/ Today, the farmer is protesting against the #Farmbills because it is threatening the Credit and Principal Risk he enjoys from the middlemen, despite the high price he pays for it.

49/ Despite the free-market rhetoric about the “Contract farming bill” facilitating risk transfer from farmers to firms who are better equipped to handle market risks, farmers wisely understand that contract farming bears the principal risk only by capping price and locking quality requirements.

50/ Pay attention to the second level in Maslow’s Theory of Hierarchy Of Needs and you will understand the high emotion that is stirring the protests.

51/ Essentially, the #FarmBills are threatening the safety and security needs of the farmers which he currently enjoys from middle-men. When you threaten the essential principal risk involved in farming, you threaten the safety of the farmer.

52/ At the end of the day, what does the Indian farmer want? He wants an assured buyer. Someone who can buy from him yesterday, today, tomorrow and six months from now. He sticks with the middle-man despite getting a bad deal when the prices go down simply because the middleman doesn’t abandon him when the prices of the produce go down.

53/ It is ironic that the most controversial bill among the three Farm Bills that were passed through the use of authoritarian power starts off saying “To provide for the creation of an ecosystem”, while disrupting the current illegible ecosystem which provides safety to farmers, while glibly talking about farmers enjoying the freedom of choice.

54/ If you see the data I shared in 38, it is obvious that they already have the freedom of choice to sell to private traders. What they need is a reliable system which can take on the principal risk on behalf of farmers and gives them an assured buyer.

55/ Until #Agritech startup ecosystem grows up to accept this challenge, status quo will remain and the farmer will leverage his political clout for the status quo to remain.

No words on thanking for this article. Thank You So Much Venky Ramachandran sir. Nandrigal.

Nice article. There are bound to be teething issues in any new beginning. Hopefully things will fall in place in the next 4-5 years. Middlemen will also be a part of the ecosystem, maybe with some other name and form. Btw, should it be 39 instead of 38 in point no. 54?