Why I Invested in Gramoday

Before I talk about it, I want to talk about my "Portfolio of Small Bets" approach to investing time and energy in life and agritech startups.

When I quit my full-time job as an agritech product manager in 2019, in hindsight, I wanted to become a venture capitalist for my ideas1 in the power-law world.

“Anytime you have outliers whose success multiplies success, you switch from the domain of the normal distribution to the land ruled by the power law—from a world in which things vary slightly to one of extreme contrasts. And once you cross that perilous frontier, you better begin to think differently.” - Sebastian Mallaby, The Power LawWho else could I expect to sponsor my living experiments to discover freedom and meaning in an age of runaway Climate Change and sustain my happily unemployed lifestyle?

My nascent skin-in-the-game approach to investing my personal funds in agritech startups that I am advising is a fractal design of my larger approach to investing my life energies.

In an uncertain world that is waking up to a climate crisis, I want to chase maximal interestingness with a portfolio of small bets in the enchanting worlds of culture and agriculture and eventually, increase the odds of making this lifestyle choice sustainable.

Agribusiness Matters began in 2020 as a small bet to observe and track the ongoing developments of the agritech universe, outside the reality distortion field created by VCs and agritech founders and hopefully discover leverage points to transform the food and agriculture system.

One thing led to another and soon enough I discovered that I was offering “Co-Founder As A Service” to a few early-stage agritech startups, delivering ecosystem services that were as much under-appreciated in the startup world as they are in the natural world.

Credits go to my agritech founder friend Narain who helped me articulate the value I was bringing to the table at a time when I didn’t know how to talk about the work I was doing with agritech startups. These relationships have been slowly maturing and I now feel ready to announce the first startup in my “portfolio of small agritech bets” - agritech startups chasing problems that are music to my ears, solving them in directional vectors that are maximally interesting to under-served customer segments.

I take the integrity of this newsletter very seriously. Other than these one-off announcements to explain my investment thesis, I don’t plan to feature agritech startups under my portfolio in this newsletter as a part of my regular agritech startup commentary.

It’s funny how life comes full circle.

In 2017, when I was building a startup (which eventually failed) that aimed to disrupt the business models of research and consulting firms like Gartner, I courted controversy by digging deep into the ethically problematic business models of Gartner.

Those articles (Part I and Part II are here) went viral, triggering anonymous confessions, backhand “C’est la vie” defences and threw me inside a stormy tea cup, whirling with hard questions about embedded conflict of interests, agency problems and ethical walls while designing platform-oriented business models.

Is it possible to build ethical walls - barriers to keep aside the conflicting parts of your business separate- without peepholes when you are tracking the agritech ecosystem as an analyst and also investing in a handful of agritech startups as an advisor?

This is going to sound cheesy, but I’ll nevertheless say it aloud: I have the conviction that I can lead by example.

I chose paid subscriptions for this newsletter primarily because I wanted my incentives to be aligned with the subscribers’. While subscriptions aren’t yet a major chunk of my income, I would happily limit my advisory services to a handful of startups under my portfolio when my subscription revenues grow bigger.

I’ll be honest - All of this is uncharted territory for me and I am figuring things out. While I will make mistakes (and have made mistakes in the past), I will definitely strive to correct them quickly and publicly.

If you are reading this and have any concerns or questions about how I am approaching this ethics policy, feel free to ping me.

Why I Invested in Gramoday

Broadly speaking in smallholding farming contexts, there are two kinds of marketplaces.

There are marketplaces which want to be middlemen (who inevitably shy away from taking inventory and principal risks) and there are marketplaces which want to empower middlemen who take inventory and principal risks.

The former tend to be vertically integrated marketplaces ($) digitizing the existing vertically integrated industry architecture. The latter tend to be horizontal marketplaces which take advantage of the unbundling of the vertically integrated business models, thanks to platforms, Cloud and AI.

Those who have been reading Agribusiness Matters for a long time would know my soft corner for the latter.

Not because I am nostalgic about old ways of doing business at this turn of the history wheel in the nick of technological transformation in agriculture.

Ever since I began to study agriculture from a system thinking lens, I am equally inclined to ask ‘What is your theory of stability?” as much as “What is your theory of change?”

If you map any agricultural supply chain from the lens of the theory of stability, you will always find something like this

As you can see, and as I’ve argued at length before, middlemen will always exist between farmers and consumers as they play a critical role that no one else currently plays in the agricultural ecosystem.

There is another reason why I have a soft spot for horizontal marketplaces that empower middlemen on the ground over verticalized marketplaces which want to be middlemen with an app.

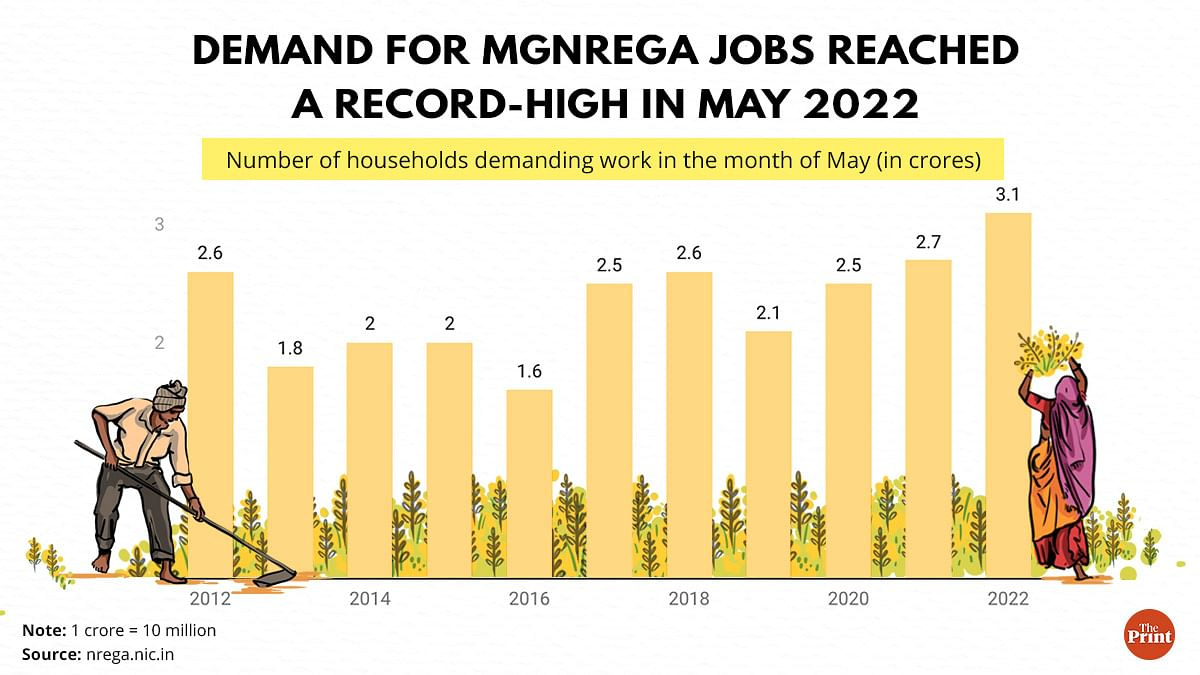

If you are tracking the rural livelihood crisis that’s unfolding in India, you would be aware of data signals pointing at an increasing number of people joining agriculture for employment from non-farm sectors like manufacturing and other informal jobs.

This largely aligns with the future of agriculture scenario models that I have been closely tracking. I explained it in greater detail many moons ago.

“The CMIE analysis says that the share of the agriculture sector in total employment has increased to 45.6 percent in 2019-20, from 42.5 per cent in 2018-19.”

More recent data from MGNREGA are also pointing in the same direction.

Given all of this, I see all the more reasons to bet on horizontal marketplaces which are aligned towards “One Nation, Many Markets” rather than “One Nation, One Market”.

One Nation, Many Markets, IMHO, is more effective in the long run than One Nation, One Market for a simple logic that has been validated with empirical data: An increase in market density (spatial competition) leads to better price discovery for farmers.

“A one standard deviation increase in competition increases farmer prices by 6.4%.” - Research Study on Market Power and Spatial Competition by Shoumitro Chatterjee

I see this in many agritech horizontal marketplaces that have been gaining momentum, riding on what Sajith Pai calls the “SaaSTra model ( SaaS + Transaction)” where "SaaS creates the wedge, and provides data to create a lending business”

Introducing Gramoday

Gramoday is a social marketplace (what NFX calls a market network) attempting to solve the mandi information asymmetry problem. What started as an MVP experiment in Whatsapp is now a mobile app with ~15K downloads, with the first 10K downloads from word-of-mouth.

- The users come from over 500 districts in the country and over 300 mandis have representation on the app

- Commission Agents, Traders and Farmers working in Potato, Onion and Garlic form the major user base

- Due to the high-frequency use case of the application, 200+ new connections are being made and ~150 new leads are being generated, every week

What I like about this social marketplace is that it…

Combines the sociality of social networks like LinkedIn with the transactionality of marketplaces.

Embeds SaaS workflows to enable traders and commission agents to upload market prices (marked by the variety of the produce) and gain long-term credibility in the marketplace, validated by the ratings and profiles of the social network.

Promotes farmers, suppliers (village-side commission agents, traders, exporters), buyers (city-side commission agents, wholesalers, processors) and their value creation and enables them to create long-term relationships in the marketplace.

The success stories of some of the early adopters of Gramoday are a clear indication of how horizontal marketplaces accelerate spatial competition, creating a win-win arrangement for buyers, farmers, and suppliers.

Sanjay Singh, a potato commission agent from Kanpur used to procure potatoes from the Agra belt and sell them in Kanpur Mandi. He created his profile with Gramoday when the team were doing MVP experiments and since then, been an active user.

His success in Potato trading, spurred by his professional page and good ratings in Gramoday, made him start his onion business. Onion farmers in MP started supplying Onion directly to Sanjay Singh in Kanpur because they got better rates compared to local markets like Indore, etc.

Krishna,a potato commission agent and supplier from Agra also has a similar story to tell.

"I have been able to supply to markets in Maharashtra and South India and grow my business apart from the sales commission in Agra Mandi” - Krishna

Gramoday was co-founded by IIT Mumbai Grads Shashank Shekhar, Himanshu Solanki and IIT BHU grad Ankit Gupta. I’ve known Shashank and Himanshu since 2019 when Gramoday was in the middle of pivoting from an ops-heavy verticalised marketplace model and after a few experiments eventually rebuilt themselves as a horizontal marketplace, with a shoestring development budget.

In one of the old audio conversations the Gramoday team had recorded with one of their customers, Rakesh a potato farmer from UP, there was one line that stayed with me for a long time

“Aap ke information , aap ke liye, theek hain. Saamne waalon ke liye bahut bada profit and loss karva sakta hain”

"The information you provide could just be information for you but for us, it decides our profit and loss for our business"

It’s one thing to put together a workable solution to tackle market price information asymmetry problems in Indian Agriculture. It’s a different beast altogether to build a marketplace, knowing the humbling difference between a market and a marketplace.

Marketplaces learn, Markets remembers. Marketplaces proposes, Markets disposes. Marketplaces are discontinuous, Markets are continuous. Markets control marketplaces by constraint and constancy. Marketplaces get all our attention, markets has all the power.

- From my earlier Season 2 article on Pace Layers of Agriculture

Market price information asymmetry is a tricky wicked problem. Are Indian Agricultural markets dominated by Mandis? The answer could be yes or no, depending on which state you are talking from.

There are diverse regulatory systems and each state has APMC acts that have rich histories which have shaped those agricultural markets. . There is incredible diversity and complexity in the way Indian agricultural markets are organized and I am excited to see how Gramoday's journey will be. I am sure it will be fun:)

Credits go to Daniel Vasallo who first introduced me to this metaphor, which rewards you handsomely upon deeper reflection. If you want to dig in more, start from here.