India's Biostimulant Sector Faces Regulatory Cholesterol

India's Biostimulant sector is caught in a strange pickle with an unsuited regulator, unscrupulous informal players who sell anything to farmers and formal players anxious about legal threats.

A silent battle is brewing between informal India (often called as Bharat) and formal India.

Whether it is in the domain of taxation or agriculture or sand mining or F&V trading, this battle is quietly shaping the future of Indian governance.

You wouldn’t hear about it unless you have your ears and feet on the ground. Before I take you to the agricultural battlefield, let me share some quick introductory meta context (at the risk of repeating myself) for those unfamiliar with India’s structural dynamics.

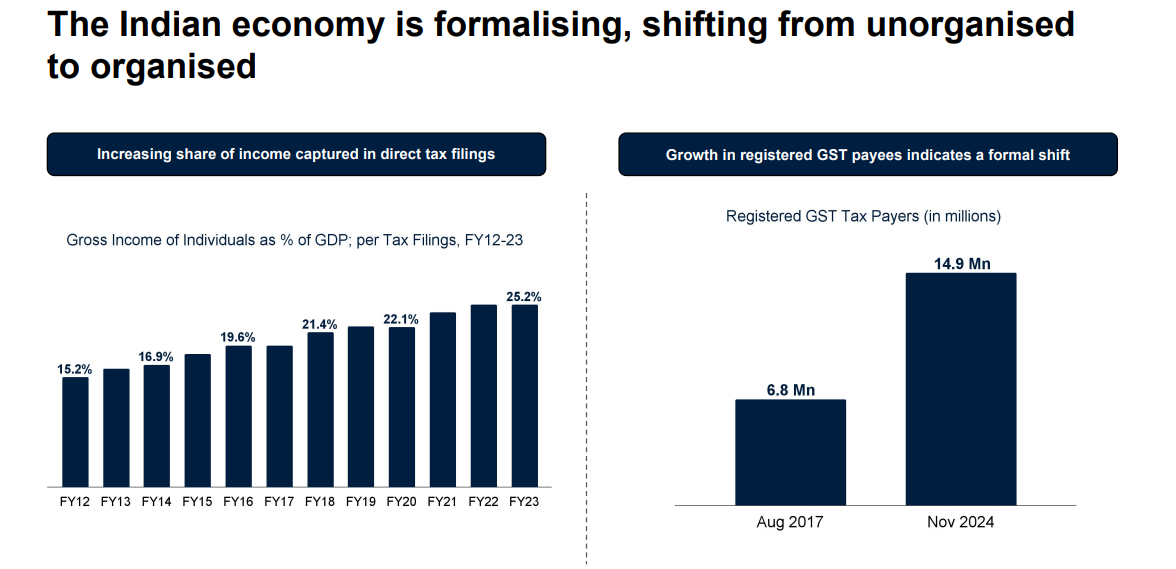

If you talk to economists, VCs bullish about India (who play with productive weed-like hype cycles) and rose-tinted entrepreneurs dreaming of resurgent and climate resilient India (Pick your poison: We are the third largest emitter of GHG emissions or We are the fourth largest economy), you would hear them talk often about how rapidly India is formalizing.

But that’s a very small sliver of the story.

It reminds me of that famous poem where the blind man held the tail of the elephant and concluded it was a slithering snake. The bigger story (given how much India depends on monsoon and how much Indians depend on Agriculture for livelihood for good and bad reasons) is much stranger than you think.

As I wrote earlier in March 2025 in greater detail with the support of a lot of numbers,

“While the share of Industry and Services have formalized steadily, agriculture has more-or-less remained the informalized elephant, with the share of informal agriculture in total GVA rising from 94.8 per cent in FY11 to 95.9 per cent in FY23.”

What I didn’t see with clarity was the head-on battle that is quietly taking place between the larger-in-size, but poorly represented/understood informal sector and smaller in size, but extremely influential formal sector across different industries and ecosystems.

Pay close attention to my language here.

While my framing may make it seem that the hapless informal sector is being bullied by the cruel formal sector (which could be true in the case of UPI-driven GST notices that were sent out to mom-and-pop traders across India), the reverse is also happening.

Isn’t reality much more complex than the cobweb narratives that accumulate in our head?

Take the case of herbicide-tolerant genetically modified Cotton. Technically, it is banned and illegal. But its informal sales has grabbed almost half of the entire India’s 3600 crore cotton seeds market (if you pay attention to the ground sources) in several states including Maharashtra.

Cotton farmers are happily growing them (while few are moving away from cotton, transitioning towards oil seeds and maize and tobacco) and the regulatory authority is pretending as if they are not watching.

I now hear rumors that the government is trying to legalize herbicide-tolerant genetically modified cotton. Interesting times. Isn’t absence of evidence evidence of absence?

Here is where things get interesting.

Unlike HTBtCotton, in the case of the biostimulant sector, the situation is the complete opposite: Informal use has made regulators visit biostimulant manufacturers’ factories ‘to make friendly connections’ (read as bribes), and in adverse circumstances, do witch hunting and legal bullying thanks to the ongoing regulatory paralysis.

Farmers have been using humic acids, amino acids, protein hydrolysates and seaweed extracts for 25-30 years, purchasing them from local dealers, relying on word-of-mouth recommendations, and adapting usage based on seasonal conditions and crop needs. This informal ecosystem involves 250+ manufacturers, 10,000+ formulators, and millions of farmers operating through relationships and trust networks rather than formal documentation.

Informal use became a regulatory target after farmers complained to India’s Agricultural Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan about "forced bundling" practices where retailers wouldn't sell subsidized DAP without biostimulant and Nano Urea purchases.

But does that mean we ram down an entire ecosystem that holds promise in delivering climate resilience to farmers?

India’s Biostimulant sector woke up to a rude shock on July 15th when Shivraj Singh Chouhan announced that biostimulant products wouldn’t be sold without scientific nod.

What does this really mean on the ground?

Despite full regulatory compliance, product efficacy validation from 261 university-led field trials, and investments in safety, quality, and innovation, no clear pathway exists today for companies to legally continue selling biostimulant products after the expiry of their G3 certifications. This sudden vacuum has triggered a full-blown operational crisis across the industry, disproportionately impacting startups, MSMEs, and rural agri-entrepreneurs.

Let me share some numbers so that you understand the scale of regulatory paralysis.

Only 45 products have received approval from over 30,000 G2 & G3 applications submitted since 2021—a 99.88% rejection rate affecting a ₹2,600-2,900 crore market serving 100+ crops.

Let us now contrast this with other countries.

As attested by this agripreneur, Pakistan achieved 3-month registration process of biostimulants through simple soil/root testing. EU provides clear guidelines despite longer timelines with standardized procedures across 27 member states. Brazil's regulatory system approved 550+ biostimulants with 60-180 day timelines through transparent, science-based processes.

India's unique institutional structure creates disadvantages absent elsewhere.

Having the world's only dedicated Ministry of Fertilizers creates chemical-subsidy bias that adversely affects biological products regulation.

Indian Micro-Fertilizer Manufacturers Association has been advocating that non-subsidized fertilizers be removed from the Essential Commodities Act (ECA), as there is no longer any shortage of fertilizers or food in the country.

Other countries integrate fertilizer policy within agricultural or environmental frameworks, enabling balanced innovation approaches. Ajay Bhartiya has delved into this peculiar problem from India's fertilizer ministry beautifully.How did India get into this mess despite taking four years to get biostimulant included within the ambit of FCO? Why did Government publish specifications without providing clarity on analysis methods?

Here is a quick timeline of events

•In 2021, the Government of India introduced the biostimulant guidelines under the Fertilizer Control Order (FCO) to bring structure and safety to this growing sector. The guidelines introduced a 3-stage approval process—G (permanent data submission)- with the intention to validate products based on efficacy, toxicity, and quality data, G2 (State specific provisional review), and G3 (temporary Pan India sales permission). Since then, 38,000+ applications were submitted for G3 approval.

•~1,000 applications backed by comprehensive data from top agricultural universities were submitted in late 2023 for permanent registrations

•As of July 2025, only 45 products have received approval under Schedule VI of the FCO.

•But no clear path on how states will implement these notifications. No infrastructure at govt level to conduct the said testing. Product availability is stalled, pending state-level licensing.

•With G3 lapsed and G review applications stalled, the entire industry has been brought to a screeching halt.

Now wait.

Why is Fertilizer Control India managing biostimulant regulations? Aren’t we doing Ctrl C+ Ctrl V of existing fertilizer and pesticide guidelines and tweaking them slightly for regulating biologicals? Why are we regulating biological products "based on % active ingredients and yield response in such reductive terms?

As Ajay Bhartiya nails it eloquently

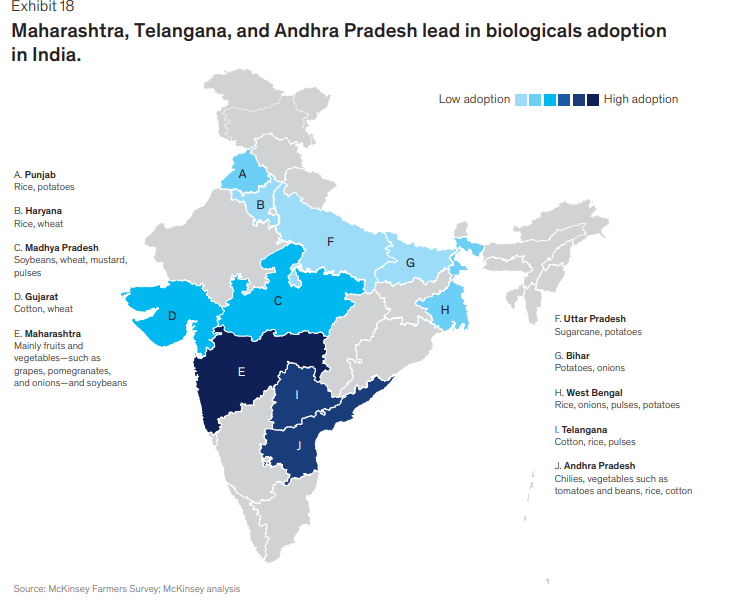

“However, the bio-business cannot be managed by a single authority like the Fertilizer Control Order (FCO) because different states interpret and implement regulations in their ways. It’s important to recognize that organic, natural, or regenerative farming is a regional matter. For example, the microbes found in the North-east states are very different from those in the deserts of Rajasthan.”

Mind you, this is not about bureaucratic inefficiency.

When you try to regulate informal and hyperlocal agricultural practices through formal centralized frameworks, you create impossible compliance requirements.

What’s worse is that you incentivize the ecosystem for wrong reasons.

For an original biostimulant registration, an entrepreneur has to spend more than 25-40 Lakhs INR while a “Me-too” product can get it registered free of cost without submitting any trial data.

The agripreneurs I spoke to complained about constant legal fears with one keeping standby armies of lawyers and god forbid even be prepared for jail if things go south. In a crisis of this kind, each state with their peculiar regulatory maze accentuates the crisis.

Maharashtra requires pesticide certificates for biological products. West Bengal tells companies to "continue business" but refuses written authorization. Only Tamil Nadu seems to have successfully implemented licenses for approved products.

While the Govt thinks that it has a moral responsibility to tame an ecosystem where the rough consensus in government quarters is that “Bio= Money”, in reality, it has an orchestrated a plane crash to destroy an entire ecosystem.

In contrast to what is happening with biostimulants, Nano Urea presents a fascinating picture of contrasts.

Achieving provisional FCO approval in February 2021 and market launch by June 2021, nano urea bypassed the regulatory paralysis affecting thousands of biostimulant applications.

By 2025, production targets 440 million bottles equivalent to 20 million tonnes of conventional urea—potentially eliminating India's 9 million tonne import requirement.

It is also true that over the past few years, farmers were quietly complaining about Nano Urea and there were lots of fraudulent activities happening on the ground with seaweed extracts mixed with pesticides (something I pointed out several years ago).

Why are we clubbing nano urea with biostimulants here? Because we are talking about the same regulatory framework but with preferential treatment for the former in contrast to what is happening with the latter.The differential treatment isn't about scientific merit.

Both nano urea and biostimulants require ICAR validation, university trials, and biosafety assessments. Both in principle ought to deliver enhanced nutrient efficiency. The difference lies in institutional positioning.

IFFCO's cooperative status provided ministerial access, distribution networks through PACS (Primary Agricultural Credit Societies) and PMKSKs (Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samridhi Kendra), and integration with subsidy mechanisms unavailable to decentralized biostimulant manufacturers.

Strategic classification determined fate. Positioning nano urea as "fertilizer" enabled established FCO pathways requiring two-season data versus multi-year validation demanded for "biostimulants."

Similar products faced radically different treatments based on regulatory categorization rather than scientific differences.

To understand how far the system has been corrupted from within, we need to understand the subsidy system.

India spends ₹2 lakh crore annually on fertilizer subsidies—nearly 10 times our budget for agricultural research investment. Taxpayers pay ₹930 per urea bag while farmers pay ₹242, creating incentives that perpetuate status quo for synthetic chemical inputs over biological alternatives.

Today, Fertilizer response rates crashed from 15 kg grain per kg nutrient in the 1970s to barely 5 kg today. Nitrogen-use efficiency declined to 34.7%, meaning two-thirds of subsidized urea volatilizes before crop utilization. Only 46% of applied nitrogen reaches plants—the rest creates water pollution and greenhouse gas emissions 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

As you can see, this zero-sum game serves nobody - the farmers, entrepreneurs-innovators and harms the planet.

Enough talk about problems. Let’s talk about solutions in increasing order of priority.

1/ Immediate G3 extensions could prevent market collapse during Kharif 2025. Can we go for fast-track pathway for products with validated dossiers, particularly those evaluated at ICAR and state agricultural universities?

2/ Method of analysis notifications should accompany all approved products immediately. Tamil Nadu's implementation model could be studied deeply to explore possibilities of replication across states through standardized procedures and central coordination.

2/ Separate subsidized from non-subsidized products within FCO to enable innovation. The Micro fertilizer manufacturer industry is now setting a precedent with self-regulation. Truthful labeling precedents from the Seed Act can be adapted enable biological competition while maintaining safety oversight.

3/ We don’t need One Nation, One Market. We definitely need “One Nation, One License” for biostimulant regime through a digital platform that can minimize state-level complexity, reduce compliance burden through central repositories accessible to states. Risk-based categorization could easily differentiate established products from novel compounds.

Mind you, the tension between formal regulations and informal agricultural practices is not going to vanish overnight. It’s a structural challenge that’s has cultural origins.

We will have to radically imagine a new indigenous system of governance that respects the need for accountability while respecting the hyperlocal needs provided by informal agricultural systems. Digital technologies powered by AI could really help. What would it take to shift the needle to design an indigenous form of governance? I am all ears.

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Agribusiness Matters”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.

India-Bharat- Hindustan ( in between)