Is Small No Longer Beautiful?

1/ Is Small No Longer Beautiful in Indian Smallholding Agriculture?

A new paper which examines how the relationship between farm size and productivity has evolved from 1975 - 2014 in India makes an interesting insight: The inverse relationship (smaller farms being more productive) has significantly weakened over time. The paper makes an interesting point (albeit obvious for those working in the sector) that is deeply relevant for those who are engaged in managed farming business: “Changes in production methods, advancements in technology, and improvements in factor markets are reducing the productivity edge that small farms once held.”

And at the same time, it is also nuanced when it comes to focusing on what matters, subtly indicating smallholders’ inevitable shift towards economics of scope over economics of scale: “Smallholders operate at a lower level of technical efficiency in value of output per acre but not in terms of profit per acre when compared to their larger counterparts.”

While crop diversification allows smallholders to mitigate risks from climatic changes and pest outbreaks, the paper shows a 1% increase in crop diversity corresponds to a 0.28% decrease in output per acre and 0.26% decrease in profit per acre. The paper documents three distinct phases:

Wave 1 (1975-1984): Strong inverse relationship - small farms more productive per acre

Wave 2 (2001-2008): Relationship weakens; positive relationship emerges for output value

Wave 3 (2009-2014): Further weakening; relationship becomes mixed/insignificant

The paper documents the uneven adoption of agricultural technology over time and more importantly, how farm households with a larger share of irrigated land exhibit greater inefficiency in both output and profit models, likely due to mismanagement such as over-irrigation or inefficient usage.

“The use of tractors rose from almost zero during Wave 1 to over 5% by the end of Wave 3. Similarly, the adoption of sprayers/dusters grew from approximately 10% during Wave 1 to 38% by the end of Wave 3, and that of submersible/electric motors grew from less than 35% during Wave 1 to more than 65% by the end of Wave 3. Advanced irrigation systems, such as sprinklers and drip systems, were only introduced after 2001 but expanded rapidly in subsequent years. This technological progress led to a significant increase in irrigable land, which grew from less than 20% in Wave 1 to over 60% by the end of Wave 3”

This weakening shift coincides with India’s persistent agricultural crisis and represents a fundamental transformation in farming dynamics.

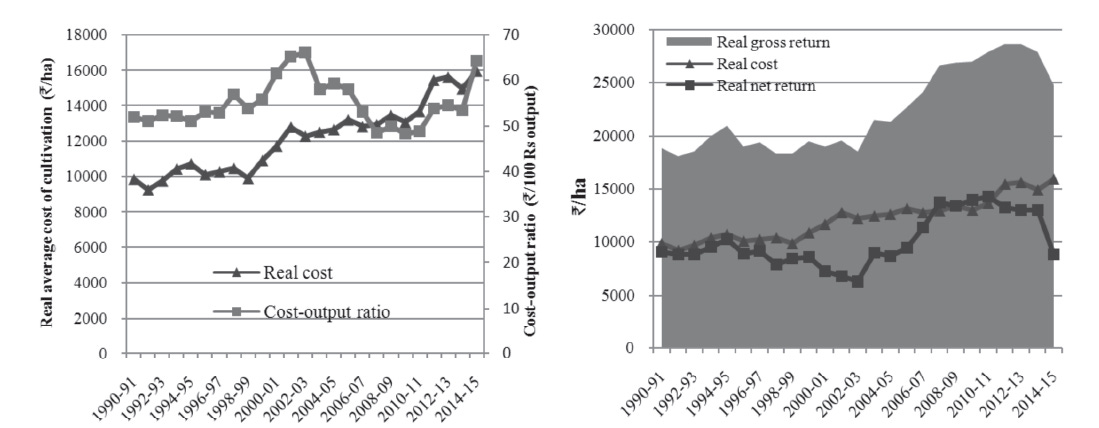

This timing shift (starting from 2009 onwards) aligns with another Niti Aayog paper I read many moons ago

“The cost incurred to produce 100 rupees of crop output increased from 51 in 1990-91 to 66 in 2002-03 and the net return declined at the rate of 2.77 per cent per year. The time period between 2002-03 to 2007-08 was a good time for Indian farmers, when the cost of producing 100 rupees of output came down to historically lowest level of 48 by the year 2007-08. Naturally, this increased the crop profitability substantially.

Post 2007-8, this optimistic story took a strong nose dive when cost of cultivation began to rise rapidly at 3.22 per cent a year, leading to shift in cost cultivation from 48 to 64 in 2014-15.”

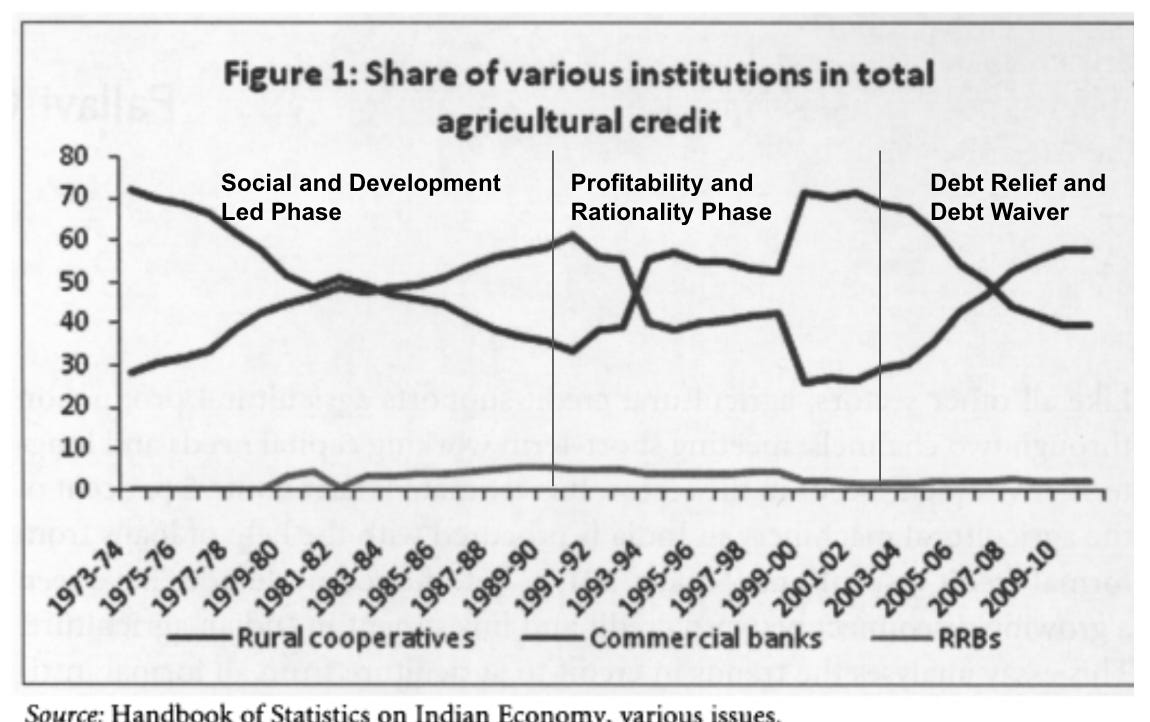

It also broadly aligns with another primer piece I wrote on Indian Agrifintech where I mapped three stages of the historical arc of agricultural credit in India.

A) ‘Social and Development’ Led Phase (1969-1990)

B) ‘Profitability and Rationalization’ Led Phase (1991-2005)

C) ‘Debt-Relief and Debt Waiver’ Led Phase (2005-Present)

Why is this weakening happening? The authors identify several drivers:

Labor intensity: Inversely related to farm size, but the gap is narrowing as labor intensity decreased by ~40% for small farms between Wave 1 and Wave 3. Large farms increased reliance on family labor while maintaining hired labor. Labor shifted from agriculture to manufacturing/services sectors

Input intensity: Small farms were most input-intensive in Wave 1. By Wave 3, large farms surpassed them in fertilizer, machinery, and chemical use. Reflects increasing mechanization and capital-intensive farming

The paper gets fascinating when it explores the divergence of labour intensity across Wave 1 and Wave 2.

“During Wave 1, the labor group employed fertilizers at higher intensities compared to other farm groups, a pattern that continued into Wave 2. In Wave 1, all farm groups, except the labor group, spent more on seeds compared to machinery. However, by Wave 2, all farm groups began spending more on machinery than on seeds.”

Besides talking about weather derivatives, agroecological collectivization and ecosystem services and more importantly land reforms, the paper doesn’t go deeper into the virtual land consolidation (through FPOs, cooperatives and other collectivization means) and physical land consolidation and only briefly talks about land reforms without going deeper on modalities emerging from the market dimension through Managed farming, Agriculture as a service and other land pooling/land tokenization models.

With 45% labour force still remaining informal labour force, we see a peculiar paradox of India suffering from massive labour shortage, despite agriculture constituting 46% of the jobs in India.

How do we increase labour productivity in agriculture? We have three choices. 1) Intensification 2) Mechanisation 3) Intensification-Mechanisation Bundle As a Service

I hope we develop more data and insights on how each of these choices are playing out in Indian Agriculture.

2/ Should Indian Agriculture Feel Inferior to its Netherland counterpart?

Few days ago,

wrote a brief piece on Indian Agriculture that was equal parts inspiring and equal parts frustrating.The inspiring part was his deeply felt angst on why India is so much behind Netherlands. Yes, as my friend rightly said in our Agripreneur Community, they have cracked the code on farm Engineering and farm Export Supply Chain (while probably hitting a blind spot when it comes to nutrient density)

But, If you’ve ever visited the hinterlands of the country and seen the innovation and the resourcefulness of the farmer thriving despite odds, you would never doubt one moment that we have incredible potential, despite the lack of formal research infrastructure.

And so the frustrating part is: Why do we have to compare ourselves with Netherlands? Why are we comparing apples to oranges, when India’s average operational holding size is 0.7 hectares? For the record, India’s average operational holding size dropped significantly from 2.28 hectares in 1970-71 to approximately 0.7 hectares in 2021-22.

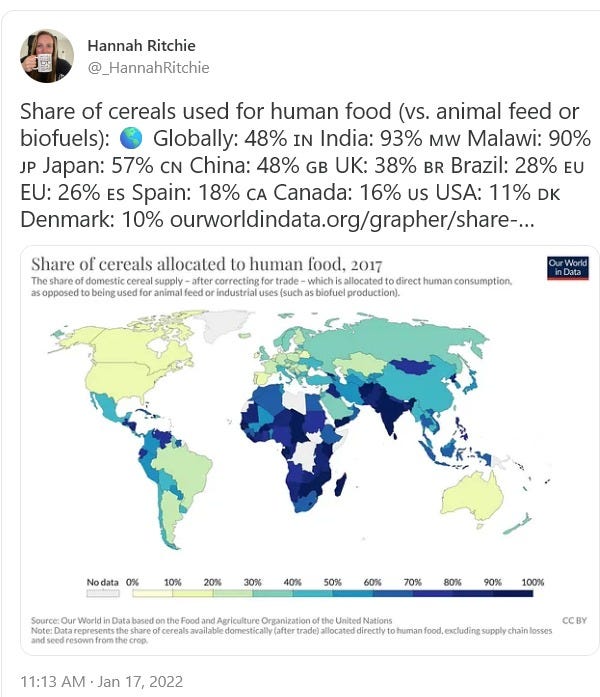

And if you want to cherry pick data that makes India look good, this is my favourite one.

What about Netherlands? Average farm size is 32 ha. Of course, this is not an apology to be complacent.

If we want to compare India with Netherlands, the real question is: For the public taxpayer money that goes into the likes of ICAR and other agricultural universities of our country, what have we accomplished in comparison with what a behemoth like Wageningen University has accomplished?

Did we produce newer variants of fertilizers that can match the soil needs of our country? What have we done with our bovine biodiversity? Why are we importing bull semen? What have we done with our indigenous rice varieties? How many have we commercialized it and created wealth for farmers? What about newer biopesticides and biofertilizers?

Dr. Balbir Singh asks this and many more uncomfortable questions here.

In October 1946, JC Kumarappa gave a brilliant prescription for Indian Agricultural Universities to aspire to become equivalent to Wageningen University.

“The real agriculture college must be situated in rural areas; their buildings, etc., should be in consonance with their surroundings and in keeping with the standards prevailing among the people they profess to serve. The principals and professors must themselves be cultivating farmers. They may well be allotted a certain acreage, out of the produce of which they can support themselves. Their activities must be confined to the needs of the people and chiefly limited to food production, short-staple cotton and such other materials in demand in the villages. They should take the lead in the supply of selected seeds and in grain storage. The medium of instruction should be the language of the locality. The student themselves would then be prospective farmers instead of job-seeking city young men whose one aim is a degree of some kind.” — J.C. Kumarappa, These Agricultural Colleges, Oct 1946

If we follow his advice, we are largely sorted. The question is: Do we have the courage to follow his advice?

Maybe, we need to reimagine a new breed of farmversity that can transcend the inferiority we feel with the likes of Wageningen University.

Instead of bringing farm to an university, why not bring an university to a farm?

I know of many farmer collective groups that have been organizing farmer study groups for more than four decades. With the available tools of coordination at our disposal, why not design a travel education curriculum that involves visiting various agro-climatic zones and learning from elite (in the truest sense) farmers who have cracked both production and markets? And why limit it to only agriculture when rural rejuvenation could also be undertaken with relevant skill and craft development?

Why limit the imagination to creating another clone of Wageningen University? Why not dream something more bigger, more impactful?

3/ Two Paths to Meaningness

For humans, there are largely two trajectories to create meaning in their lives.

1) Make enough money; discover the hunger of deep fulfillment in doing things that are beyond financial ROI and embark on a quest of meaningness

Jim Carrey once famously said this and I often think about it: “I think everybody should get rich and famous and do everything they ever dreamed of so they can see that it’s not the answer”

Among many code-to-croppers who are entering agriculture, I see many embark on this path of least resistance. It aligns with the Maslowian Hierarchy thesis. You are sorted out on basics. Now you go for higher needs.

After attending the recent Agripreneurs Retreat, Manohar Malani outlined the various archetypes of folks who are plunging into the world of Agriculture

1️⃣ The Corporate Dropouts

They’ve done well, made money, and now want to get their hands dirty.

Discovering that farming doesn’t obey PowerPoint — but they’ve got the cushion (and curiosity) to fail, learn, and inspire others.

2️⃣ The Returnees

Financially secure, back in their villages, building organic supply chains and local pride. Less about ROI, more about roots.

3️⃣ The Entrepreneurs

They see opportunity — spot a problem, fix it, scale it.

Some use AI and sensors; others just use sharp observation.

Tech is optional. Problem-solving isn’t.

4️⃣ The Change Catalysts

Social ventures aiming to improve farmer livelihoods.

Purpose-first, but surprisingly scalable.

5️⃣ The Idealists

Fueled by passion for sustainability, still figuring out how ideals survive market realities. (We’ve all been there.)

6️⃣ The Blenders

Part dreamer, part doer. Balancing idealism with strategy. They might just define what “new agriculture” looks like.

The only glitch with this meaningness path is that by the time you embark on meaningness path, you are already in your forties/fifties. You may not have higher reserves of energy. Unless you have trained your body enough, you may not have the same energy you had once you were in your prime years.

2) Be rigid enough to make money by only doing those things that give you a deep sense of fulfillment.

This is a very risky move. But, increasingly I see the next generation, with deeper awareness about personal finance, embark on it. I was adamant about this path in my life and happy with the price I paid to embark on this path. Of course, I had my set of privileges that helped me embark on this path. For the longest time of my life, I could only see this path of meaningness. It took me a while to see the first path as an equally powerful path of meaningness.

What has been your trajectory of meaningness? Did you enter agriculture in pursuit of meaningness? How have you dealt with this body’s deep hunger for purpose and meaning? Do share in the comments.

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Agribusiness Matters”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.