Private Agritech, Public Agritech

When we work in food and agriculture systems, we tend to operate either in binary zones of non-profit “development” or for-profit “agribusiness”. As it happens with most binaries in life, this distinction is now blurring to the point of becoming irrelevant.

Take the case of Gates Ag One who recent set up office in St. Louis Cortex Innovation District where ‘roughly half of all US agricultural production sits within a 500-mile radius of St. Louis.’:

“As a nonprofit affiliate of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, we act like an agricultural innovation accelerator, connecting what is currently a fragmented R&D pipeline for smallholders.

We champion a coordinated, networked approach to innovation that generates and shares knowledge freely, believing that collaboration creates the best results.”

Few months ago, I coined the term “Impact Middlemen” to categorize these emerging breed of androgynous players in food and agriculture systems who are powered with “for-profit” operating system inside, while dealing with “not-for-profit” customers outside (and that includes governments as well) and sit cosily in this weird, liminal space creating ecosystemic synergies to accelerate impact at scale.

Impact Middlemen:

Much like middlemen who make double coincidences of wants unnecessary for farmers to sell their produce, Impact middlemen make double coincidences of wants unnecessary for philanthropists and nonprofits. Impact middlemen advise nonprofits and philanthropies, set targets, implement programs, partner with foundations and corporations, and measure and monitor their progress.

The burgeoning rise of “Impact Middlemen” (and I am not the first one to point out its second-order consequences) has been one of the most intriguing recent developments in the ongoing evolution of our food and agriculture systems in the wake of runaway Climate Change.

Few days ago, I returned from two back-to-back retreats - the Agri-Founders retreat which I had organized with few agritech founder friends in Bangalore- and the second round of conversations with Impact sector leaders who are part of “Alliance to Push Harder”

Both the retreats, one with agri-founders, and the other with Impact sector leaders, were as different as chalk and cheese. And yet, they were bound by the essential thread that deeply aligns with my core mission at Agribusiness Matters: Ecosystem Engineering

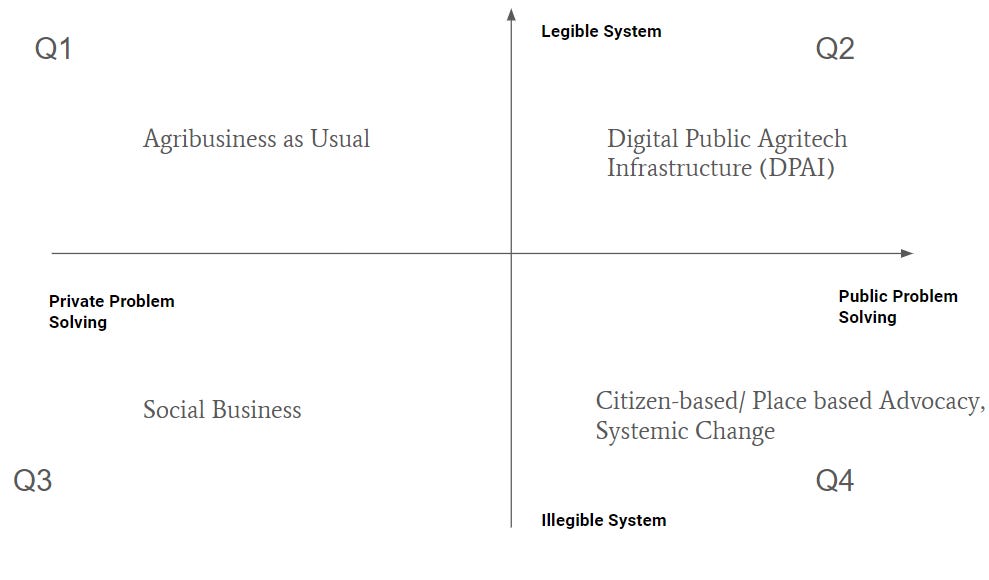

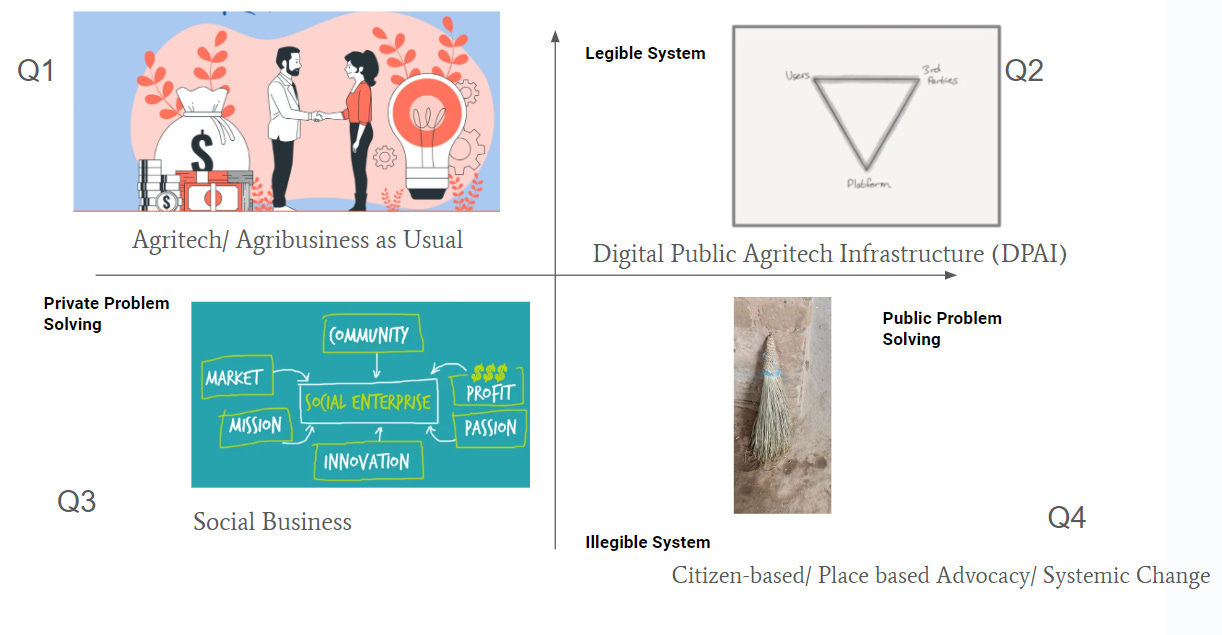

As I reflect on what transpired in both of these retreats, what is increasingly clear is that we need to replace the vaguely confusing “for-profit”/”not-for-profit” categories (especially inside native food and agriculture context) with public/private problem solving if we are serious about moving the agritech landscape towards ecosystemic possibilities.

What is public problem solving?

Authors Tara Dawson McGuinness & Anne-Marie Slaughter in their Stanford Social Review Paper distill it to four elements

People-centered: puts people with needs and capabilities at the center of programs and policies (human-centered design)

Experimental: starts small and scouts for local solutions, tests ideas and concepts, shifts to modular contracting, and experiments before national rollouts

Data-enabled: leverages data (big and small) to assess problems, monitor progress, and evaluate what works

Designed to scale: assesses and plans for how to expand impact and scale

Yeah right. So what? What this definition hides is way more fascinating than what it reveals. As the authors write in their paper,

“For most of the 20th century, “public problem solving” was synonymous with policy making: the work of figuring out what government should do and how to get it done through an executive order, regulation, or law”

Today, the scope of public problem solving has shifted exponentially with the advent of Digital Public Infrastructure, Impact middlemen, and legions of consultants performing functions outsourced by governments like India’s, struggling with poor state capacity (a comparable country like Brazil has seven times more public employees for every thousand citizens, a data point I learned in Karthik Muralidharan’s brilliant book, “Accelerating India’s Development”)

As an agritech analyst, I pay deep attention to situational awareness of the agribusiness market landscape and been advising folks often that, if you want to play the game in the long run, you can’t afford to play chess without understanding the chessboard deeply in the first place.

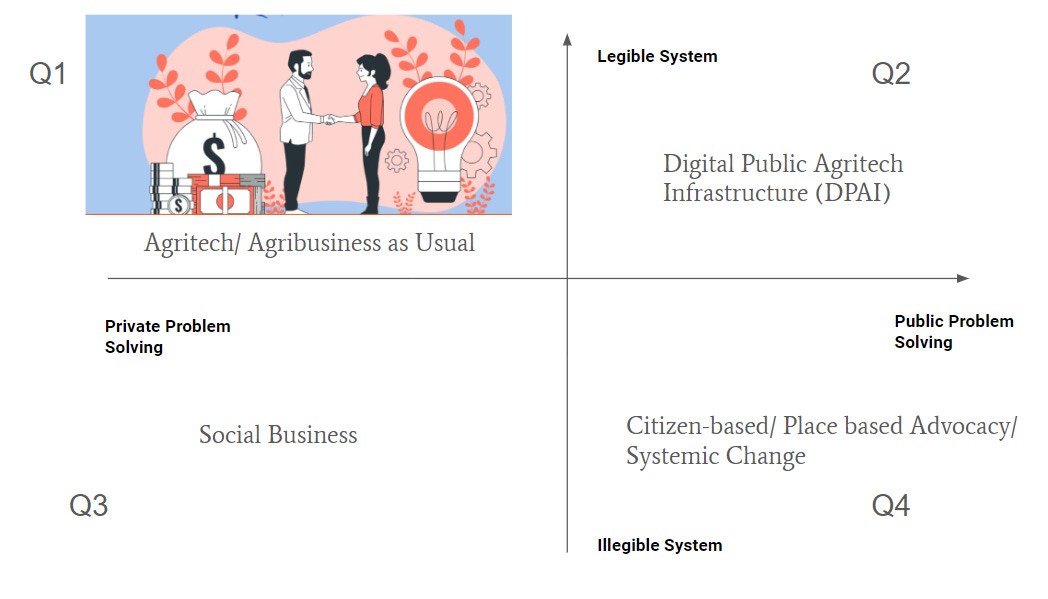

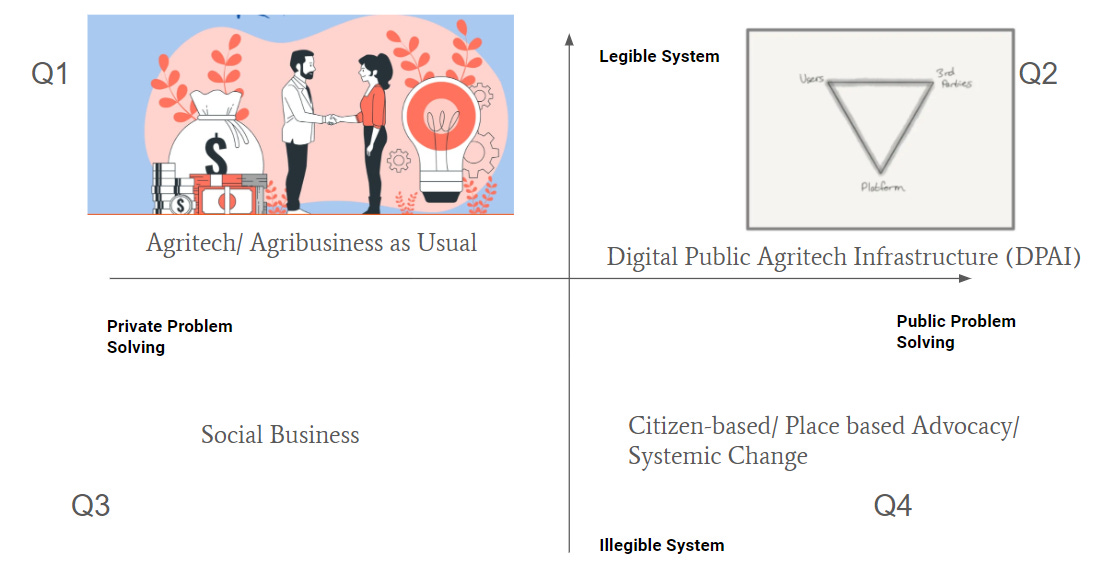

If I were to look at the emerging chessboard all of us are playing to shape the future of food and agriculture systems, in the eyes of this recovering management consultant with fondness of 2x2s, it looks something like this.

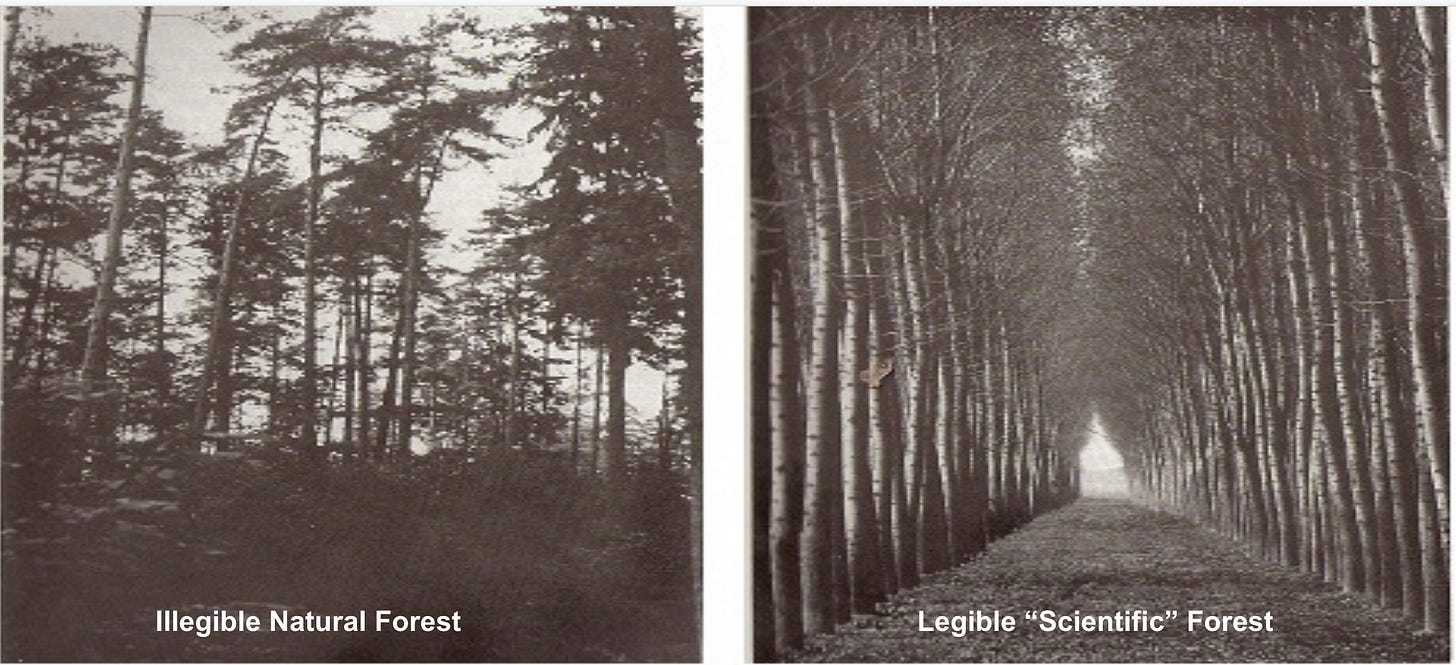

If you’ve been reading Agribusiness Matters, you would know that the Y-axis comes from my favourite book, “Seeing Like a State”

Before we get into the quadrants, let’s address the elephant in the room: Why does this distinction between public agritech and private agritech matter?

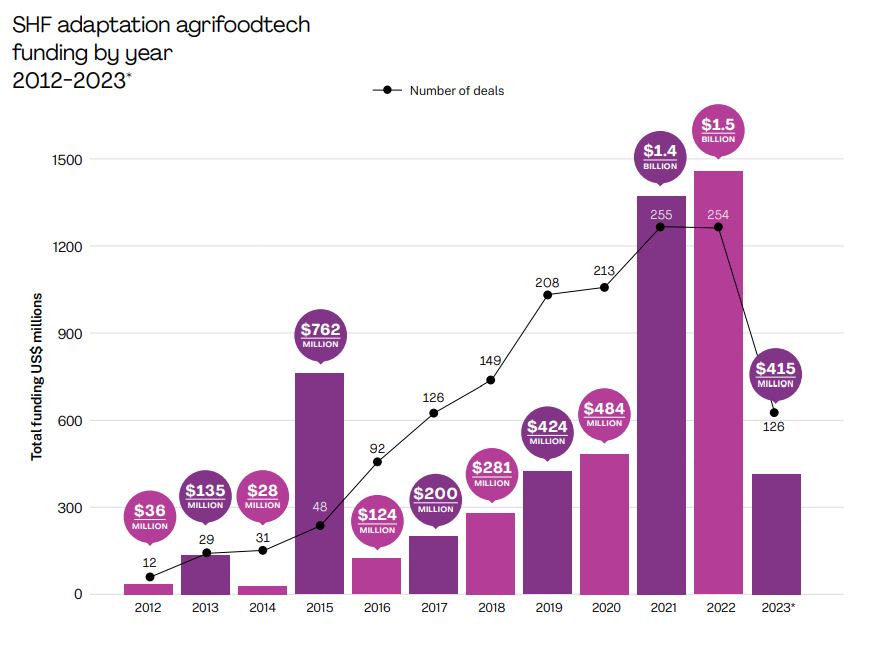

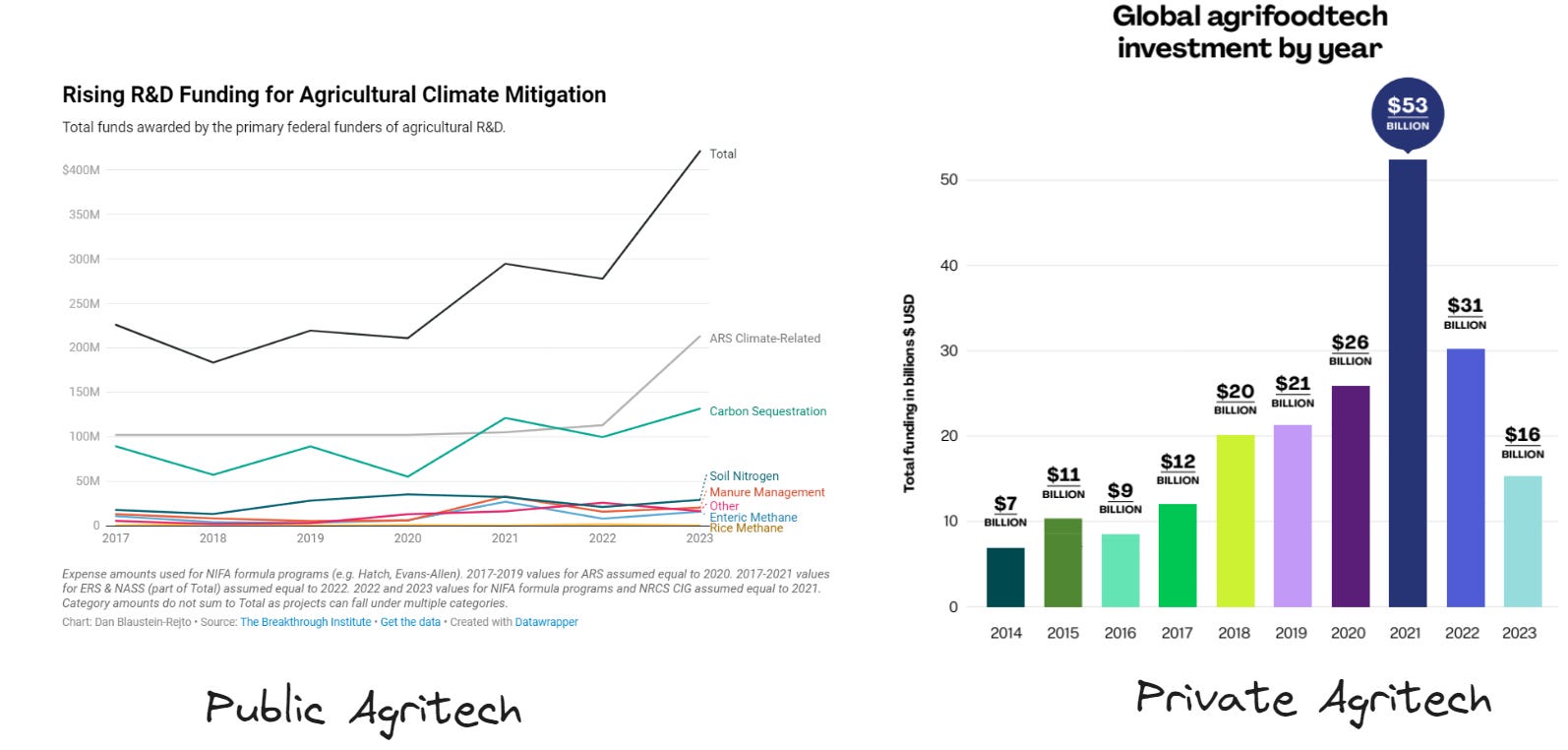

When I compare Agfunder’s Global agrifoodtech investment trends with Breakthrough journal’s research on largest federal funders of US agricultural R&D, the stark difference between public and private agritech becomes obvious.

Although you could argue that this is a case of apples and oranges comparison, given that 40% of global agrifoodtech investment numbers comes from Americas, I am juxtaposing these two charts to illustrate the yawning gap in terms of funding that typically happens in a public agritech context vis-a-vis private agritech context.

While the numbers on public agritech (focusing specifically on agricultural climate mitigation) don’t take into account the full picture of how much governments spend on food security, it is important to acknowledge the yawning asymmetry/inequality at play.

Whether it is India or any other country across the world, what we are spending on public agritech infrastructure is way lower than what we are spending in private agritech infrastructure.

According to Global Center on adaptation, $15 billion of annual adaptation investment in agriculture is needed for the African continent and $260 Million (1.7%) went into agrifoodtech VC funding in 2023.

Let us now get into the the action-packed world of each of these four quadrants. Why is this categorisation between public and private problem solving important for shaping the future of food and agriculture systems?

Most Agritech/Climate-tech VCs in the sector are stuck in Q1 and have inattentional blindness to understand the dynamics of activities happening in Q2, Q3, Q4. While they may relate to what is happening in Q2 and may consider moving there, they are largely averse and cynical of the activities happening in Q3 and Q4. They are prone to dismiss activities happening in Q3 and Q4 as “NGO” which has become a strange cuss word in these circles. I wrote about this and why this view needs to be challenged here.

Because of the funding/ infrastructural/talent asymmetry between public and private agritech, most new players who enter this space assume that Q1 is the only chessboard worth playing agritech chess games on and refuse to see the enormous possibility in moving towards Q2 with enormous scaling potential.

It takes a few farsighted agritech players- Kuza in Africa comes to the top of my mind- to see the potential of building Digital Public Agritech Infrastructure and work towards the same to tackle the climate adaptation challenges in Africa. I wrote about what is happening in the Indian DPI context few moons ago for the subscribers of this newsletter.

2. Currently a lot of hope is riding on Q2 given governments are panicking to control their food and agriculture systems in the wake of extreme climate change volatilities and are proposing digital public infrastructure to control the perception of these food and agriculture systems, if not the system per se.

That said, buoyed by the success of Internet HTTPS infrastructure, a lot of idealists are building digital public infrastructure to decentralize food and agriculture systems and reimagine cooperative federalism between the Center and the State in an Indian context.

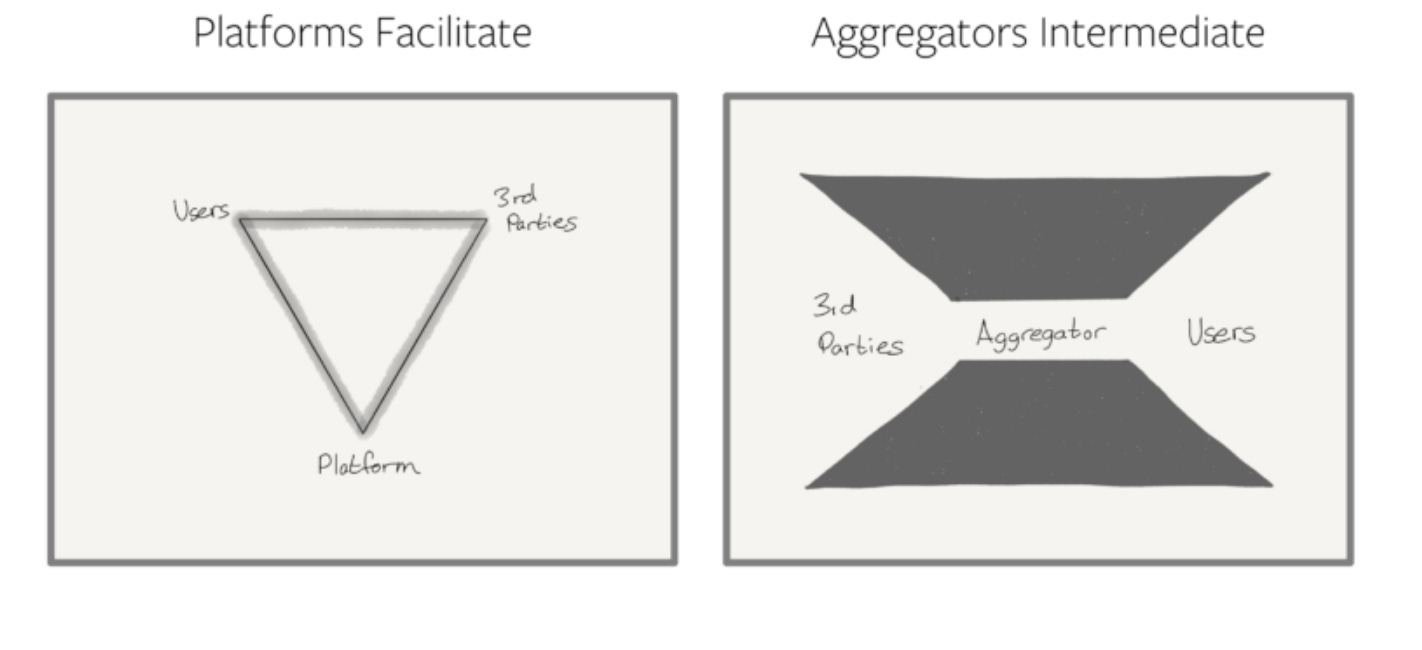

Platformisation potential is immense in Q2, while many Q1 agritech participants are entering the space seeing the aggregation potential in Q2.

And at the same time, we need to build Q2 specific measurement systems that aren’t necessarily borrowed from Q1. Gross Capital Formation, as I’ve written before, is a Q2 metric and it would be worthwhile to assess the performance of Q2 players by such metrics instead of Q1 metrics that don’t belong in Q2.

A platform is when the economic value of everybody that uses it, exceeds the value of the company that creates it” — Bill Gates

“Platforms are powerful because they facilitate a relationship between 3rd-party suppliers and end users; Aggregators, on the other hand, intermediate and control it. - Ben Thompson”

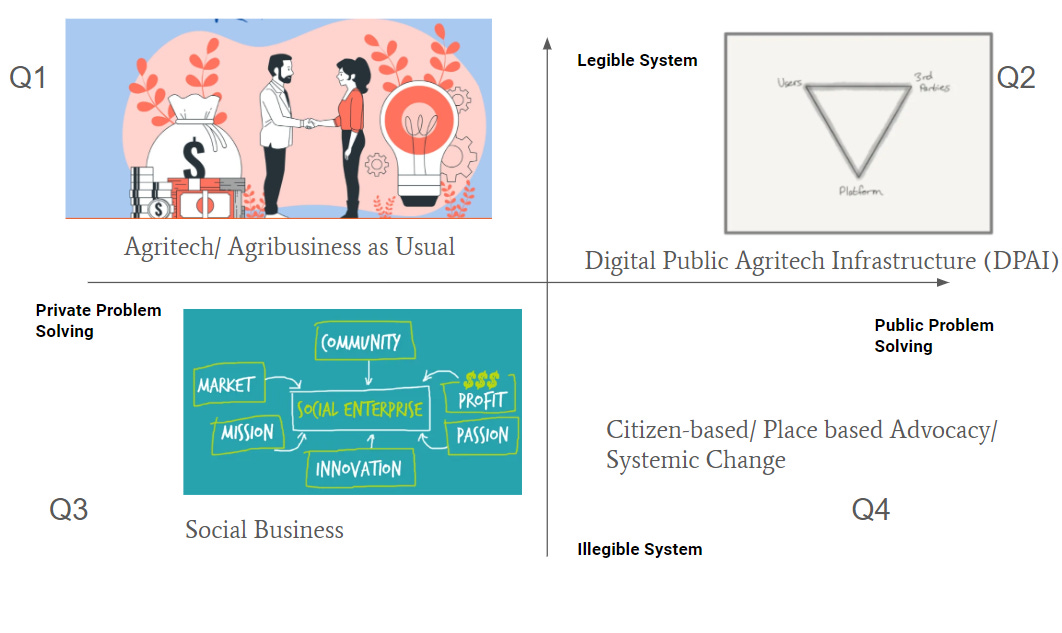

Several agritech players who didn’t want to be in Q1, and didn’t have the resources to move towards Q2, ended up being in Q3. These “social businesses” tackled harder “wicked” problems that defied easy, legible measurement systems. How do you measure microbial activity in the soil? How do you measure grower’s agency in moving away from subsidies and doles? How do you measure the nutrient density of the produce we eat as it travels from farm to fork? How do you measure the opportunity cost in minimizing textile waste?

Social businesses are not swayed by what is easy to measure in a legible system. But, they struggle to grow big as such illegible measurement systems they operate in are yet to receive mainstream recognition. How can we unlock the potential of those working in Q3 and help them collaborate better and move towards Q2? What resources and playbooks would be required to help those working in Q3 to move towards Q2?

I know of a player operating in Q3 to reduce the cost of credit for Indian farmer and democratize agricultural credit eventually pivot towards Q1 friendly business model as he couldn’t receive any form of support to sustain and grow his social business. While both Q1 and Q3 have their respective places, we have to arrest the exodus of founders deserting Q3 because of lack of support.

Cropin, on the other hand, as I detailed in my recent subscriber-only edition, pivoted from Q1 to Q3 because of the customers they ended up serving.

Let’s be clear - Q3 has immense potential and my biggest concern is that it doesn’t end up becoming a graveyard of incredible potential players who had big aspirations to create deep systemic change.

4. True blue Impact sector players have their roots firmly set in Q4. They chase moonshot goals, tackling harder public problems, driven by a deeper sense of purpose. They are also deeply attuned to the sense of place and sense of house in which they are serving. However, the funding donor/philanthropy ecosystem that powers their activities don’t really understand what is happening in Q4. And so most impact players end up wearing disguised Q3/Q1 hats while staying true to their Q4 purpose underneath.

How can we empower Q4 players to collaborate in Q2? What kind of platform typologies would be required to bring together Q4 players to unlock ecosystemic possibilities in Q2? Today, most agritech solutions don’t have a sense of place and are, infact, working towards “deplacing” their solutions. I will explore “sense of place” and agritech later at greater depth.

And so, when you are working on Q4, one important question would be - Are you representing the place or are you representing the solution? - so that the difference between Q1/Q3 and Q4 is adequately clear.

This framework has been incidentally deeply helpful for me in understanding my mission in creating ecosystem engineering at Agribusiness Matters.

I quit my agritech product manager job in 2019 to move from Q1 to see how to create ecosystemic impact across Q2 and Q4 in the domain of food and agriculture systems. And in this journey, I have been lucky enough to work across Q1, Q3, Q2 and Q4 quadrants. Bulk of my writings in Agribusiness Matters have been about helping Q1 players get a sense of Q2 and move towards platformising possiblities. How do I accelerate my work to create deep impact in Q4 and steer the entire ecosystem towards Q2- will remain one of my core “raison d’etre” question that will drive what I do at Agribusiness Matters.

When I look at each of these four quadrants to foster collaboration among them, the possibilities are immense and huge. As cheesy at it may sound, It feels wonderful to be alive and work on these possibilities in this path I have set out for myself. It imbues my work with a deep sense of meaning and purpose.

Programming Note: I will be going on a summer vacation break for the next week and will be back soon with regular “State of Agritech” programming. I thank you deeply for supporting Agribusiness Matters.

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Agribusiness Matters”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.

You might take a look at this article by Clark that thinks of innovation from a engineering vs market disruption context. Clark was Clay Christensen thesis advisor https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0048733385900216