The Deadlock of Industrial Agriculture

How Industrial Agriculture paradigm creates a zero-sum game with lose-lose proposition for farmers, consumers and, of course, the planet.

This is the third of a series of posts (The first is here) where I explore the idea of Pace Layers (introduced here and elaborated further here) to design alternative markets and marketplaces (the second is here) in smallholding contexts that could create and meet the demand for sustainable food and fiber products and sustain rural livelihoods.

This essay in particular is inspired by several conversations and insights I’ve learned from my friends Vivek and Anurag who’ve earned the hardened battle scars of dealing with the traditional agricultural markets through their brave attempts to reshape them.

Unless you are a computer nerd like me, I don’t expect you to understand the concept of “deadlock”. However, if you’ve driven on Indian roads, I am sure you would intuitively grok it.

As my Irish friend who recently had the first taste of Indian traffic chaos poetically put it, it is “mutually agreed upon chaos” - soothing words to cope with the Stockholm Syndrome you experience when you drive in Indian metropolitan cities (especially after driving outside India).

Uncannily enough, the deeper I study the Industrial Agriculture paradigm and the rules which shape the logjam I’ve increasingly become numb to-in all these years of immersion inside the traditional agricultural markets-I can’t stop wondering what it would take to change the rules of the game.

If this logjam has lasted for this long, surely there must be a reason. Doesn’t it?

How has industrial agriculture shaped the traditional agricultural markets? What are the unsaid rules of the market?

If we are serious about flipping the script-making a win-win proposition for the farmers, consumers and the planet-we ought to spend more time understanding the problem at hand.

Let’s start from the obvious.

Have you wondered why growers grow their food in a separate patch (mostly with no synthetic chemical inputs) and the rest for the markets they serve? In my field visits across Europe, Latin America, and India, I’ve seen this so many times that I often used to wonder if there is something far deeper that I am not seeing.

In doing what the growers are doing, what are they really doing?

By creating a distinction in their farm plots between the “consumption” that goes for themselves (and their family) and the “production” that goes towards the markets, they are faithfully replicating the behavior of the market fractally.

I first heard the terminology of “production region market” and “consumption region market” from my friends Vivek and Anurag and over time, it started to grow over me as I started groping for clues to understand how the Industrial agriculture paradigm shaped the traditional agricultural markets.

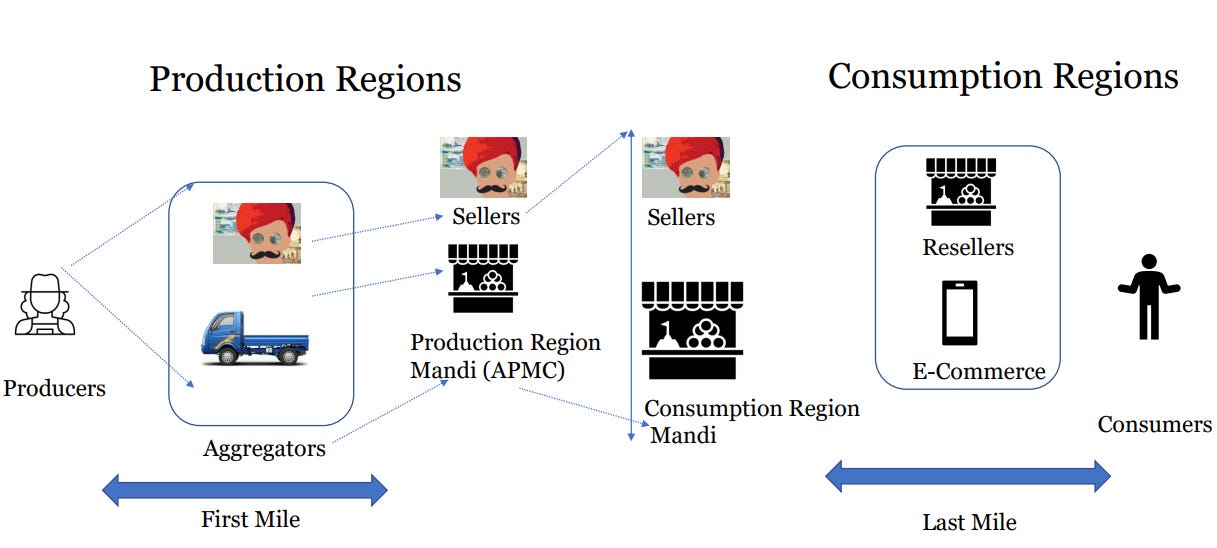

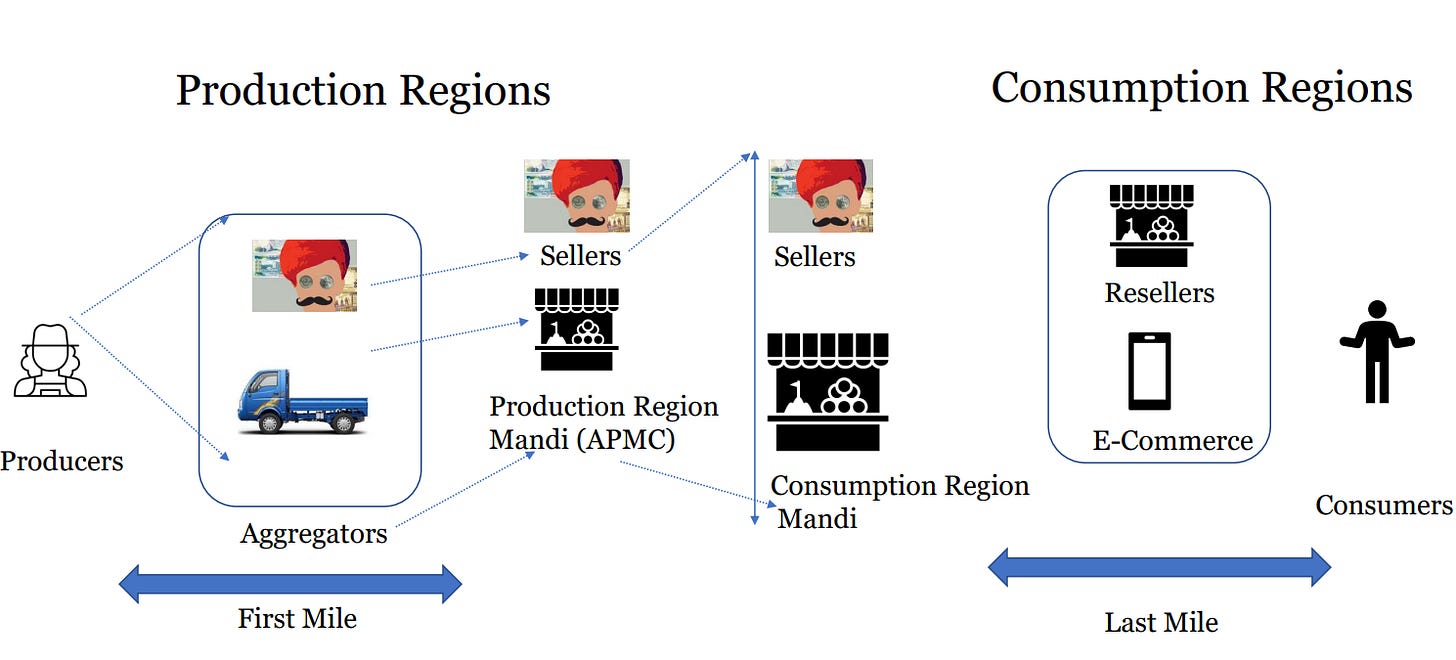

If you were to paint the structural Indian market context in broad strokes and trace the long journey of the food from the producer up to the consumer, it would start to look like this.

Here is a quick primer 101 from Vivek about understanding centrally regulated Mandis (markets, as they are locally called).

If you start to play out the permutation and combination of different traders trading across production and consumption region markets, agricultural markets will start to look like Pacman games where each one is trying to pass on the risk to the next person in the value chain and play the “carrot” arbitration margin game with the “stick” of diminishing returns of the quality of the produce in hand.

Understanding the agricultural markets through this framework is critical as it shows the workings of the complete system. Complete….broken…system.

It clearly shows why production region markets are not producer-focused and consumption region markets are not consumer-focused. More importantly, it blows up a cherished myth to smithereens.

“Farm to Fork” is a myth for what the grower is producing exactly in line with the market and policies that have shaped and incentivized him or her to produce.

Why is it important to differentiate the production region market from the consumption region market?

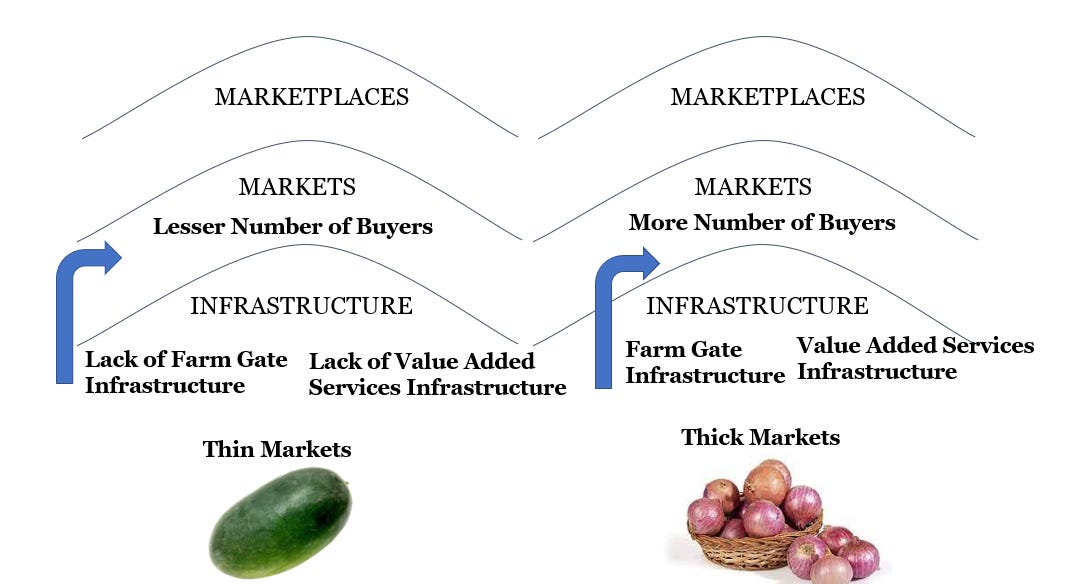

As I discussed in my previous post, because traders and middlemen control the crucial infrastructure that governs the transaction, produce markets remain thin.

Because the produce markets are thin, the value of the produce subsumes the value of the services involved in transporting the produce from point A to point B.

Because of the value of the produce subsumes the value of the services involved in transporting the produce, price discovery and sale of the produce are always coupled in the traditional agricultural markets.

Voila! There lies an important clue to enable the creation of thick markets: How do we ensure that markets remain thick (with a greater number of buyers)? Decoupling price discovery from the sale of the produce.

Of course, this is easier said than done as most of the agritech players vying for better margins tend to go for vertical agritech models where price discovery is inevitably coupled with the sale of the produce. And so, we end up digitizing the incumbent system instead of transforming it.

Because the price discovery and the sale of the produce are coupled in traditional agricultural markets, quality and grade parameters are never standardized across the journey of the value chain. Every vendor gets to define quality and grade in their way, as it is their currency of trading.

Because quality and grade parameters are never standardized, the price of the produce is location-dependent.

Voila! There lies another clue to enable the creation of thick markets: How do we ensure that markets remain thick (with a greater number of buyers). Make sure that quality and grade parameters are standardized in a way that they remain agnostic of where the produce is produced and sold.

To sum things up, what are the unsaid rules of the market in an industrial agriculture paradigm?

Price becomes a trophy of pride for farmers (even though they may be bleeding red if only they looked at their balance sheet).

Scaling is a function of the credit and capital you can infuse into the transaction and so the bigger the transaction goes; we end up recreating the same conditions which lead to thin markets.

Bull-whip effect is inevitable in the agri-output supply chain as there are…

a) …multiple intermediaries ✔

b) ...time lag between Supply and Demand ✔

3) …variation in demand and supply ✔

Acquiring marginal customers is a matter of negotiating prices in line with the risk undertaken through scaling capital.

Traders bundle price discovery with selling to improve their share of margin in the trade.

What is the central thesis behind the Industrial agriculture paradigm?

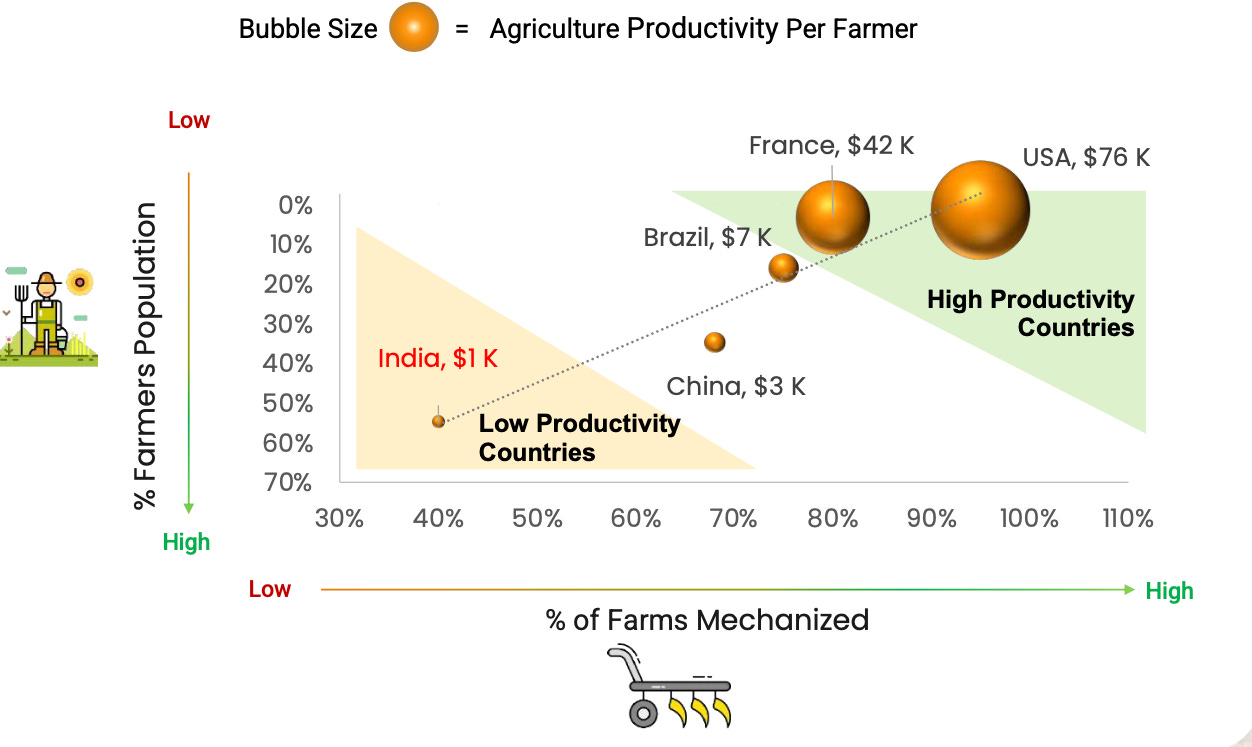

If you strip it to essential basics, under the industrial agriculture paradigm, you have two ways to improve the labor productivity of agriculture.

Intensification: (with irrigation, fertilizers, HYV, pesticides, etc) to get higher yields per hectare (land productivity)

Motorization (with tractors, combine harvesters, drones) to crop more land per farmer.

I borrow this framing from Bruno Dorin’s paper on agro-industry to agroecology

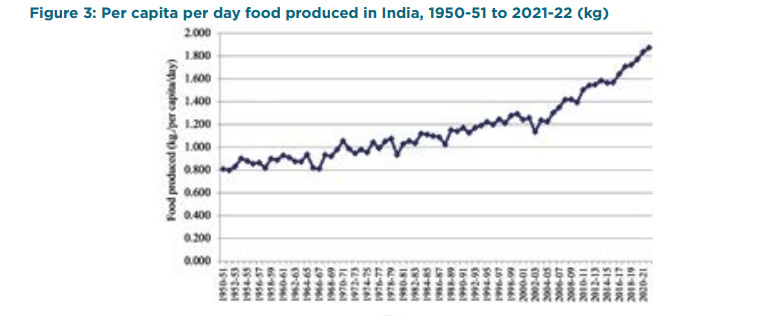

India has made significant strides in intensification of inputs, with food production increasing from 0.81 kg of food per person per day during the 1950s to 1.258 kg/person/day during 2000-01.

In a research paper, Ramesh Chand profiled the tremendous growth in food production we have seen in this country.

“India recorded a 50 percent increase in per capita food production in the first 50 years after 1950-51. The next 50 percent increase has been recorded in less than 25 years, that is, half of the previous period. This is the result of two factors: (a) slowdown in population increase and (b) acceleration in the growth rate of food production, especially after 2006-07.”

There is one catch though.

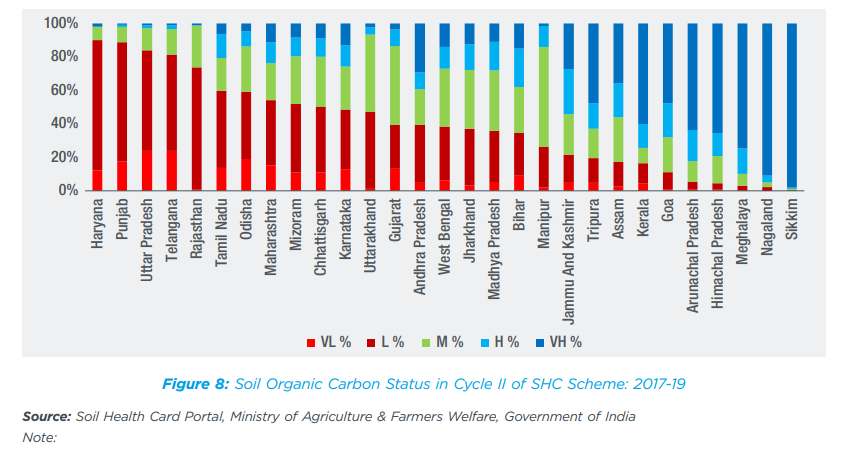

This growth has come at a price. This growth has led to environmental damage, evident from the declining soil organic content. As per Ashok Dalwai, CEO, of the National Rainfed Area Authority, ‘Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) content in India has come down to 0.3 percent from 1 percent in the past 70 years’. Even if you look at other data sources, this is evident.

As I’ve documented the warnings of scientists before, When India runs out of groundwater, cropping intensity will reduce by 20% nationwide and by 68% in groundwater-depleted regions of Central and Northwestern India by 2025.

How has India progressed with motorization (and mechanization at large)? As the below infographic I found in the Agrictools Pitch deck shows, we have a long way to go.

A recent survey on the state of mechanization in the five states of Assam, Gujarat, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu India neatly sums up the current picture.

TL; DR: Skill Training and building service capabilities are extremely crucial.

“Across states, it is found that land preparation operations are being done by tractors. But other activities vary. Weeding stands out as the only activity which has less mechanized tools across all the states. Even states like Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh which have widespread use of machines, lacks adoption of weeding machines. Irrigation technologies also observe high difference. Adoption is higher in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu but not in other states. Assam and Odisha are still relying on manual operations for majority of the activities. The findings suggest labour issues in all the states and demand of affordable machines is observed. There are only few cases of formal trainings of the operator and the finding indicates informal trainings through family and friends. For skill assessment, skill should be considered on the basis of the information and awareness of the operators rather than only considering source of the skill i.e., training through formal institutes.”

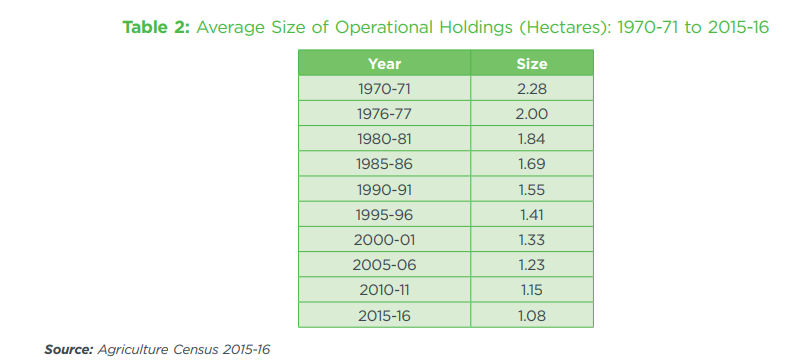

The challenge in India is compounded by the fact that lands have fragmented and when they fall below a threshold, mechanization is extremely difficult, leaving us with no other option other than use digital means to consolidate demand for mechanization (which is a fascinating opportunity for startups operating in this space)

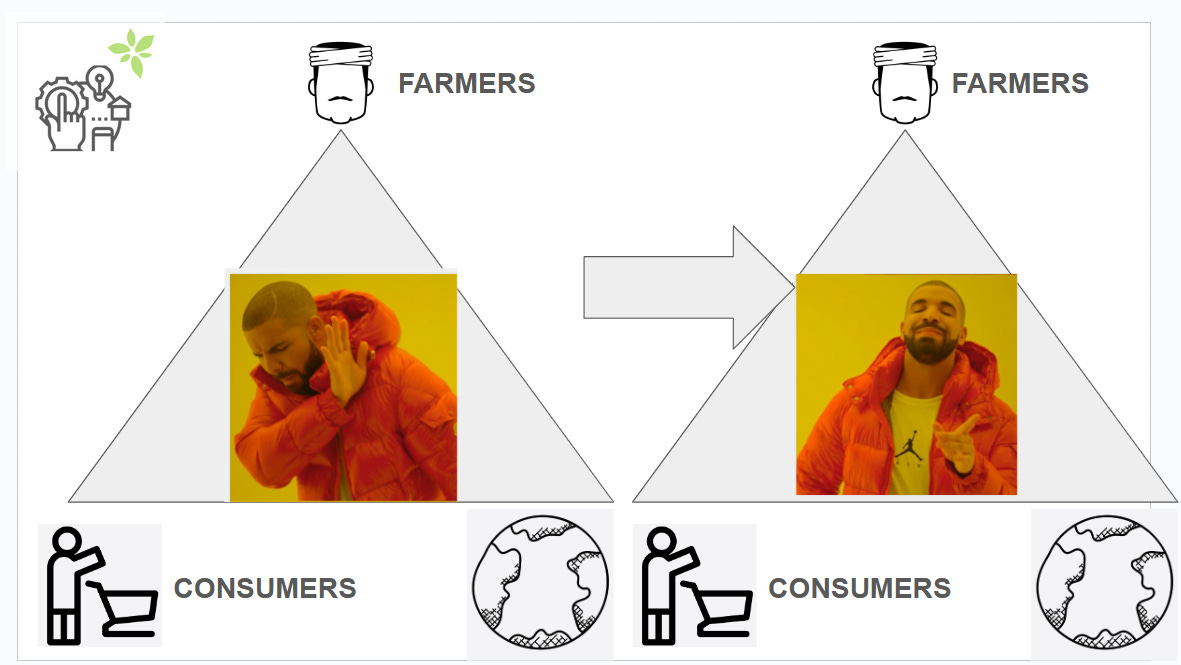

What makes the Industrial agricultural paradigm a deadlock situation is precisely this: Producers wait for the consumption region markets to solve their problems and consumers wait for the production region markets to solve their problems.

Let’s take the case of millets.

Producers of millets wait for MSP signals to improve their production systems while consumers hope that producers will magically embrace millets and transition from subsidy-driven, water-guzzling, paddy-rice-sugarcane production systems.

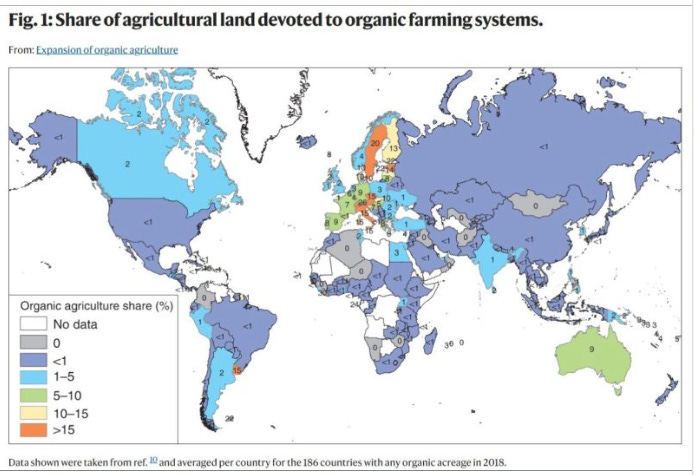

Today, for all the promise agroecology and regenerative agriculture hold, it hasn’t yet built sufficient alternative market structure and hence ends up beaten up black and blue inside the market structures that have been built for the industrial agriculture paradigm.

If we are serious about the audacity of hope called agroecology, we need to break the duality of production and consumption region market dynamics. Beyond farmer markets, beyond organic cooperatives, beyond community-supported agriculture, beyond payments for ecosystem services to regenerative farmers, we need to build alternative market structures from the ground up to scale up regenerative agriculture.

As Andy Dufresne writes in his letter to Red, “Hope is a good thing, maybe the best of things, and good thing never dies.”.

Let’s hope:)

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Agribusiness Matters”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.

Farmers will do better for a nickel against every gyaan paper written around this subject. I urge you to just start growing your own food as much as possible - and save these business models for the accountants.

Else become an accountant - and throw a currency per land piece number for the sharks and crows.

Everything else in the middle is just another noisy attention seeking child who hasn't done what is needed to realize what is needed to be done.

Love and kind compliments to you for your effort - but ducks don't take credit for the effort they put into moving rocks with their paddling.

Well done. You do have one repeated and blatant mistake. The current toxic from input to product model is certainly not agriculture. I urge you to refer to it as “agribusiness”