Hierarchy of Indian Food Retail

It is impossible to understand the psychology of food retail in India without understanding colonization and its scars on the Indian psyche.

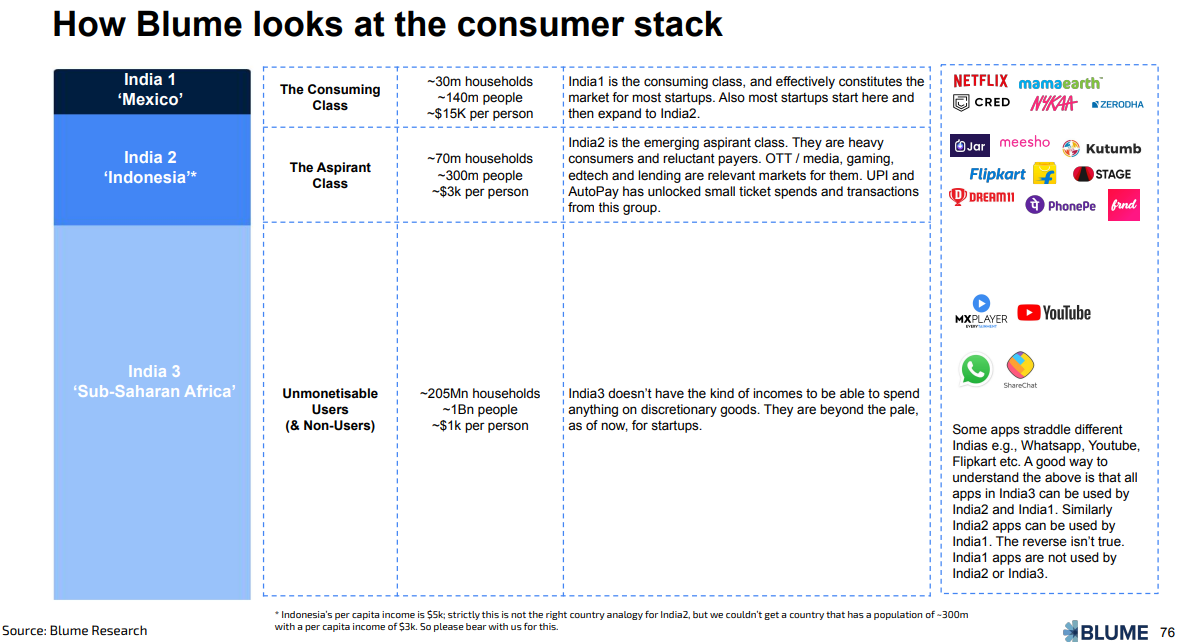

Few days ago, an Indian agripreneur friend showed me an Instagram reel of a fancy retail outlet that was selling exotic fruits to India 1. If you think about it, there is a hierarchy of retail selling experiences in the way India 1/India 2/ India 31 buys food.

First is status-driven selling.

Your products might be tax-payer subsidized trash. (Killers of the Cereal Hamster Wheel anyone?) But you focus on making customer feel high-status in your precincts. Installing air conditioner in the store is sufficient to create this status uplift. I’ve heard anecdotes of my friends from rural India sharing how they perceive the store differently once an air-conditioner is installed. Instructing customers to keep their shoes outside while entering (as a token of religiousness of the store and its products) is another way. There are loads of nuances in all of these. This is also where where India’s colonized psyche plays a huge role.

For majority of Indians, when we see fancy looking shops with neat aisles and clear demarcations, we get the status kick of being foreigners inside our brown skins. We enter the shop simply to savor the vicarious experience being a high-status foreigner. Naturally, with this, we also get triggered by the fear that we might be left behind our neighbours and those whom we perceive as “equal” in status.

Btw, I am writing all of this in -“we” terms - loving awareness of non-judgmental observation of my countrymen and the shared traumas we carry from our history. I have personally seen this closely and worked on these to the extent I can. It is a reality of our country, after several centuries of colonization.

India is a half-colonized country. We are neither settler cultures (as it happened in the case of Aborigines, or Maoris) nor are we truly indigenous cultures. Of course, there is also a political wave that is fueling this decolonization wave in zero-sum means. Just because we are collectively discovering meaning in decolonizing ourselves doesn’t mean we have the license to engage in othering.High-status buying in India is mostly Indians trying to aspire/ape/imitate being Europeans and Americans. This is also the space where the insidious assumption of “because it is expensive, it must be good” plays out. These assumptions play a havoc in our psyche because of the high-status place context where buying happens.

Our unconscious inner monologue is more often to the tune of “Because it’s high status and expensive, it must be good and healthy for me” . This is exactly the reason why organic food is a luxury belief in India for most parts.

Second comes looks-driven selling.

This is again relatively harder than status-driven selling, although sometimes both play out like a flywheel. Shinier products, clean farms (which even Indian farmers are now beginning to embrace through mulching sheets to imitate/impress their European counterparts and their carbon certification auditors) are all part of status games that feed off each other. There are studies in Europe where farmers have applied pesticides simply to improve the looks of their apples.

In the case of looks-driven selling in F&V, it is also incentivized by mandi dynamics. It makes better economic sense for traders and middlemen to incentivise looks-driven selling over everything else.

“Farms mainly marketing via intermediaries are 23.9-29.6% more likely to spray cosmetic pesticides for visual purposes compared to farms mainly direct marketing.” (Source)

Third comes taste-driven selling.

Informal India (which takes lion’s share in food systems) does this better than formal India. This is one of the reason why foreigners who come to India rave about Indian food. Take a look at what Tyler Cowen has to say about Indian food recently.

“Why is the food so good? I have several overlapping hypotheses, most of them coming from my background as an economist. Interestingly, India’s culinary advantages can be traced to some good and some not-so-good aspects of Indian society.

First, food supply chains here are typically very short. Trucking, refrigeration and other aspects of modernity are widespread, but a lot of supply chains are left over from a time when those were luxuries. So if you are eating a vegetable, there is a good chance it came from nearby. That usually means it is more fresh and tastes better.” - Tyler Cowen

Mind you, if you are a fly in the wall of a VC meeting India’s urban agripreneurs, you will hear the same praise wearing sad-looking clothes of problems.

India’s food supply chain needs transformation. Why? Food supply chains are short. Refrigeration and Logistics penetration is low.

Essentially, we are looking at the fundamental paradox underpinning Indian food system. We are also looking at the quiet political turf battle between formal India and informal India.

There is a strange theory in India (and applicable to South Asia) that underpins taste-driven selling. The taste of an eatery is often inversely proportional to its decor and ambience. Although this is shifting now a bit, in most parts of rurbanized India, this still holds true.

This affects farmers both positively and adversely. While five star chefs use high quality rice varieties to improve taste, in certain foods like biryani, the rice varieties mostly don’t matter as they are so much overcooked.

If you are an Indian food chef who wants to take authentic Indian food to global places, this is the central conundrum you are often dealing with. You can source the best veggies on Earth if you want to come up with a salad where your customers can experience the veggies in its loving physicality.

If you want to cook Undhiyu (Bless heavens if you’ve tasted this from finest chefs of Gujarat) or Aviyal (Bless heavens if you’ve tasted this from finest Brahmin cooks in Palakkad) with residue-free vegetables, you can never convince your customers through their taste buds that their veggies are healthy for a simple reason. Your veggies don’t survive the assault of cooking in the first place.

Fourth comes values-driven selling.

If you’ve been paying attention, you would have noticed that I haven’t included health-conscious selling.

For a reason.

Health-conscious selling is slippery slope (as we don’t have a way of intuitively grokking its complexity) and hence customers are wired to rely on other illegible drivers to gauge health. And health doesn’t often correlate with quality.

Given the AI wave we are in, I also suspect we are in the midst of a strange macroeconomic period where the value of being human is diminishing and ergo, we don’t have strong drivers to invest in human health.

That said, if you are looking for true north, health-conscious selling is indistinguishable from values-driven selling. And that’s why it is hard. Values-driven selling takes time. Trust batteries slowly accumulate over time in this form of selling, with every interaction adding up by 1%.

Most VCs aren’t willing to invest in values-driven segment for this reason. It doesn’t yield sufficient LP loving returns, although it is now slowly changing.

Building a business with values-driven selling might seem like chasing a niche 0.001% audience, but it pays deep dividends with wallet share in the long run. It is also the form of selling that is ideal for direct-to- farmer trade commerce and other models that prioritize Impact over Scale.

Do you agree with this hierarchy of food retail? What did I miss in this big-picture view of food retail in India? What are your thoughts? I am all ears.

So, what do you think?

How happy are you with today’s edition? I would love to get your candid feedback. Your feedback will be anonymous. Two questions. 1 Minute. Thanks.🙏

💗 If you like “Agribusiness Matters”, please click on Like at the bottom and share it with your friend.

This categorisation comes from the famous Indus Valley Report which segments India . I reviewed its insights and limitations from an agricultural standpoint here. Bear in Mind. India3 is NOT Rural.